This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

BBC

BBCAs Martina Canchi Nate walks through the Bolivian jungle, red butterflies fluttering around her, we have to ask her to pause - our team can’t keep up.

Her ID card shows she’s 84, but within 10 minutes, she digs up three yucca trees to extract the tubers from the roots, and with just two strokes of her knife, cuts down a plantain tree.

She slings a huge bunch of the fruit on her back and begins the walk home from her chaco - the patch of land where she grows cassava, corn, plantains and rice.

Martina is one of 16,000 Tsimanes (pronounced “chee-may-nay") - a semi-nomadic indigenous community living deep in the Amazon rainforest, 600km (375 miles) north of Bolivia’s largest city, La Paz.

Her vigour is not unusual for Tsimanes of her age. Scientists have concluded the group has the healthiest arteries ever studied, and that their brains age more slowly than those of people in North America, Europe and elsewhere.

The Tsimanes are a rarity. They are one of the last peoples on the planet to live a fully subsistence lifestyle of hunting, foraging and farming. The group is also large enough to provide a sizeable scientific sample, and researchers, led by anthropologist Hillard Kaplan of the University of New Mexico, have studied it for two decades.

Tsimanes are constantly active - hunting animals, planting food and weaving roofs.

Less than 10% of their daylight hours are spent in sedentary activities, compared with 54% in industrial populations. An average hunt, for example, lasts more than eight hours and covers 18km.

They live on the Maniqui River, approximately 100km by boat from the nearest town, and have had little access to processed foods, alcohol and cigarettes.

The researchers found that only 14% of the calories they eat are from fat, compared with 34% in the US. Their foods are high in fibre and 72% of their calories come from carbohydrates, compared with 52% in the US.

Proteins come from animals they hunt, such as birds, monkeys and fish. When it comes to cooking, traditionally, there is no frying.

Michael Gurven

Michael GurvenThe initial work of Prof Kaplan and his colleague, Michael Gurven of the University of California, Santa Barbara, was anthropological. But they noticed the elderly Tsimanes did not show signs of diseases typical of old age such as hypertension, diabetes or heart problems.

Then a study published in 2013 caught their attention. A team led by US cardiologist Randall C Thompson used CT scanning to examine 137 mummies from ancient Egyptian, Inca and Unangan civilisations.

As humans age, a build-up of fats, cholesterol and other substances can make arteries thicken or harden, causing atherosclerosis. They found signs of this in 47 of the mummies, challenging assumptions that it is caused by modern lifestyles.

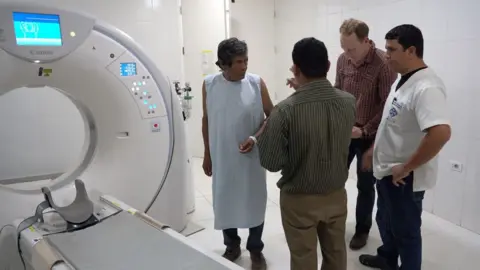

The two research teams joined forces and carried out CT scans on 705 Tsimanes over the age of 40, looking for coronary artery calcium (CAC) - a sign of clogged-up blood vessels and risk of a heart attack.

Their study, first published in The Lancet in 2017, showed 65% of the Tsimanes over 75 had no CAC. In comparison, most Americans of that age (80%) do have signs of it.

As Kaplan puts it: “A 75-year-old Tsimane's arteries are more like a 50-year-old American's arteries.”

A second phase, published in 2023 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, found elderly Tsimanes showed up to 70% less brain atrophy than people of the same age in industrialised countries such as the UK, Japan and the US.

“We found zero cases of Alzheimer's among the entire adult population - it is remarkable,” Bolivian doctor Daniel Eid Rodríguez, a medical co-ordinator for the researchers, tells us.

Working out the ages of the Tsimanes is not an exact science, however. Some have difficulty counting, as they have not been taught numbers well. They told us they are guided by records of Christian missions in the area or by how long they have known each other. The scientists do calculations based on the ages of a person’s children.

According to their records, Hilda is 81, but she says recently her family killed a pig to celebrate her “100th birthday or something like that”.

Juan, who says he is 78, takes us out hunting. His hair is dark, his eyes lively and his hands muscular and firm. We watch as he stalks a small taitetú - a hairy, wild pig - which manages to sneak away through the foliage and escape.

He admits he does feel his age: “Now the most difficult thing is my body. I don’t walk far any more… it will be two days at most.”

Martina agrees. Tsimane women are known for weaving roofs from jatata, a plant that grows deep in the jungle. To find it, Martina must walk for three hours there and three hours back, carrying the branches on her back.

“I do it once or twice a month, although now it's harder for me,” she says.

Many Tsimanes never reach old age, though. When the study began, their average life expectancy was barely 45 years - now it’s risen to 50.

At the clinic where the scans take place, Dr Eid asks the elderly woman about their families as they prepare to be examined.

Counting on her fingers, one woman says sadly that she had six children, of which five died. Another says she had 12, of which four died - one more says she has nine children still alive, but another three died.

“These people who reach the age of 80 were the ones who managed to survive a childhood full of diseases and infections,” says Dr Eid.

The researchers believe all the Tsimanes have experienced some sort of infection by parasites or worms during their lifetimes. They also found high levels of pathogens and inflammation, suggesting the Tsimanes’ bodies were constantly fighting infections.

This has led them to wonder whether these early infections could be another factor - in addition to diet and exercise - behind the health of the elderly Tsimanes.

The community’s lifestyle is, however, changing.

Juan says he has not been able to hunt a large enough animal in months. A series of forest fires at the end of 2023 destroyed nearly two million hectares of jungle and forest.

"The fire made the animals leave,” he says.

He has now begun raising livestock and shows us four beef steers he hopes will provide protein for the family later this year.

Dr Eid says the use of boats with an outboard motor - known as peque-peque - is also bringing change. It makes markets easier to reach, giving the Tsimane access to foods such as sugar, flour and oil.

And he points out that it means they are rowing less than before - “one of the most demanding physical activities”.

Twenty years ago, there were barely any cases of diabetes. Now they are beginning to appear, while cholesterol levels have also begun to increase among the younger population, the researchers have found.

“Any small change in their habits ends up affecting these health indices,” says Dr Eid.

And the researchers themselves have had an impact over their 20 years of involvement - arranging better access to healthcare for the Tsimanes, from cataract operations to treatment for broken bones and snake bites.

But for Hilda, old age is not something to be taken too seriously. “I'm not afraid of dying,” she tells us with a laugh, “because they're going to bury me and I'm going to stay there… very still."

Africana55 Radio

Africana55 Radio