This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Support truly

independent journalism

Our mission is to deliver unbiased, fact-based reporting that holds power to account and exposes the truth.

Whether $5 or $50, every contribution counts.

Support us to deliver journalism without an agenda.

Louise Thomas

Editor

Sven-Goran Eriksson’s unassuming nature could camouflage the extraordinary nature of his footballing life. He went from being a 27-year-old assistant manager in the Swedish third division to England’s first foreign manager and one of the most successful coaches of his generation.

In England, he will be mostly remembered for the ultimately underwhelming end to tournaments, the supposedly “Golden Generation” stumbling in three consecutive quarter-finals, and the sense of what might have been – though his successors, Steve McClaren and Fabio Capello, fared worse with the same players – but his feats before then give him a strong case to be Sweden’s greatest manager. He was one of the finest anywhere in the two decades before receiving a call from his agent, Athole Still, whom he assumed was joking when he asked if Eriksson was interested in the England post.

The subsequent six years were defined by missed penalties and metatarsals, by Wayne Rooney’s stamp on Cristiano Ronaldo, by David Seaman being lobbed by Ronaldinho, by fake sheikhs and Ulrika Jonsson. Within that, there were matches and moments to savour: the 5-1 demolition of Germany in Munich in 2001 remains one of the most astounding results and seismic triumphs in England’s history, lending a sense that glory beckoned. There was the cathartic win over Argentina in the 2002 World Cup group stages. There were the quarter-finals where England led, against Brazil in 2002 and Portugal in 2004, each encouraging a nation to dream. There was the eventual conclusion that Eriksson was not actually the Golden Generation’s alchemist.

Perhaps there was the irony that the first foreigner to take charge of the national team proved more English than the English: Eriksson was addicted to 4-4-2, forever influenced by Bob Houghton and Roy Hodgson, who had introduced the back four to Sweden in the 1970s. It meant Steven Gerrard and Frank Lampard were thrust together as a mismatched duo, rather than being liberated in a 4-3-3 with a defensive midfielder.

Eriksson’s understated manner meant he seemed too passive, perhaps too starstruck. Managing Roberto Mancini and Juan Sebastian Veron in Italy made him more flexible, but perhaps led to a situation where England’s big names – and captain David Beckham in particular – enjoyed too much power. The national team came to feel like a celebrity circus, with Eriksson, a man who looked like football’s answer to John Major, the unlikely lothario who joined his players on the front pages. There were times when his love life was more interesting than England’s brand of football.

Eriksson’s willingness to flirt with club jobs – Chelsea in particular – as well as women contributed to the impression he was an overpaid underachiever; in the final reckoning, he belongs in the second tier of England managers, below Sir Alf Ramsey, Sir Bobby Robson, Terry Venables and Gareth Southgate, alongside Ron Greenwood, but probably better than the rest.

Two quotes seemed to sum up his reign; one from him, one about him. “First half good, second half not so good,” as Eriksson once said, seemed to sum up his team, who could lose their way after his half-time words; indeed, Euro 2004 was probably when his England peaked and the second part of his tenure was less enticing. “England needed Winston Churchill but got Iain Duncan Smith” – a quote attributed to Southgate, though he has denied saying it – seemed a devastating critique of Eriksson’s lack of impact at the interval in the 2002 quarter-final.

Yet behind the bland facade was a personal charm and a dry sense of humour that came across to those who knew him. The tributes to Eriksson began in January 2024 when he announced he was suffering from terminal cancer and there remained a warmth from his former players; Eriksson had often shown a loyalty to them, along with a forgiving nature. Football’s amiable wanderer was far more likeable than some who have prospered in his profession.

And it is worth noting that while Eriksson’s time with England lasted fewer than six years, his managerial career spanned more than 40. The rest of it can be divided into two – before England and after, one laden with trophies, the other containing none. First half good, second half not so good; or, more accurately, first half remarkable, second half reasonable.

But his finest achievements stand the test of time. Only two Swedish teams have won European trophies and Eriksson was the trailblazer. It is still more admirable because the Hamburg side his IFK Goteborg team demolished 4-0 on aggregate in the 1982 Uefa Cup final won the Bundesliga that season and the European Cup the following year; nor was Goteborg’s an easy route to the final. The second, incidentally, the 1986-87 Goteborg side, were under Eriksson’s former assistant Gunder Bengtsson, giving him an indirect influence there.

That first Uefa Cup victory surprised Eriksson himself and catapulted him into another sphere, with Portuguese superclub Benfica and into Serie A, when it was the world’s dominant and most glamorous league. He succeeded in both. His Benfica team only lost the European Cup final to one of the definitive sides in football history – Arrigo Sacchi’s AC Milan. Since the Swede in 1990, no one has taken Benfica to a European Cup semi-final, let alone the final. Only Jose Mourinho has steered a Portuguese club that far. If that reflects the changing dynamics of European football, then it is a telling coincidence that in the last three decades, Mourinho and Eriksson are also the only foreign managers to win Serie A.

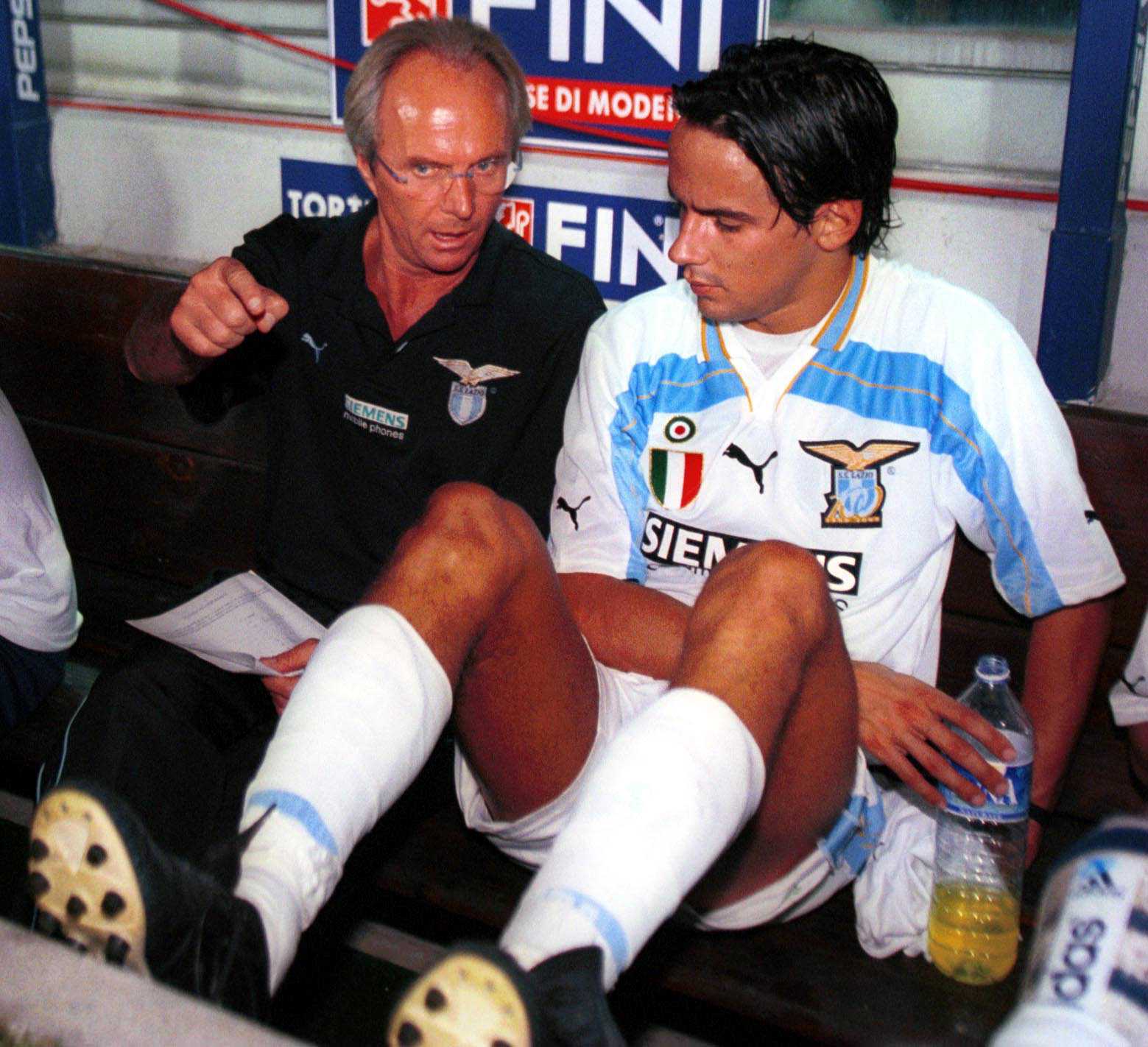

The 2000 triumph was only the second Scudetto in Lazio’s history, their first for 26 years, their last to date and when the standard of Serie A has arguably never been higher. Although it was partly created by extraordinary, and ultimately unaffordable, expenditure – with owner Sergio Cragnotti breaking the Italian transfer record for Christian Vieri and then the world record to buy Hernan Crespo – Lazio’s only European trophies also came under Eriksson. His total of five major European finals gives him a claim to greatness. He won the Coppa Italia with three different clubs and in three different decades; he did a terrific job with a stylish Sampdoria team and was a penalty shootout away from guiding them to a European final too. Until Capello, no one took the England job with a better CV.

After England, there was an eclectic element to Eriksson’s journeys. He never reclaimed his place at the top table, though he went to a third World Cup with Ivory Coast, was a couple of points from winning the Chinese Super League and managed in an Asian Champions League quarter-final.

He proved a popular figure in his one season at Manchester City, aided by a brief spell at the top of the table and a derby double over Manchester United. The Anglophile dropped into the Football League; arguably he underachieved at Leicester. He walked away without a pay-off to help Notts County when they were in financial trouble but followed the money in China. He finished up with the Philippines but his love of football was such that he was still sporting director at Karlstad before his cancer diagnosis ended an epic career.

The undistinguished player who became a globetrotting manager, Sven-Goran Eriksson may leave a sense of what his England could, and perhaps should, have done. But for Goteborg, Benfica and Lazio, there will be proof of what he did accomplish and, years later, how astonishing it remains.

Africana55 Radio

Africana55 Radio