This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

BBC/ShineTV

BBC/ShineTVPresenter Gregg Wallace is a national figure, who has been in people’s living rooms several times a week for 20 years.

His programmes, most prominently MasterChef, are made by independent production companies.

But his name and face are associated with the BBC, and, as allegations continue to emerge, the corporation is under fire.

It’s the last thing it needs, so soon after other high profile scandals including the disgraced BBC News presenter Huw Edwards.

The BBC has questions to answer about the allegations over what it knew about Wallace’s behaviour on and off set, and - if it was alerted to these types of allegations - what it did about them.

BBC News has been made aware of two occasions when complaints were made. One, by the radio host Aasmah Mir, related to Celebrity MasterChef in 2017.

She says she complained to the production company behind the show and later spoke to the BBC’s Kate Phillips who was then controller for entertainment commissioning. I understand Phillips was later assured that the issue had been addressed.

Another complaint, just a year afterwards, concerned Impossible Celebrities, made by a different production company.

In a letter from 2018 seen by BBC News, Phillips wrote that she had spoken to Wallace for 90 minutes to make clear what the BBC expected of him. She also confirmed in the letter that many aspects of his behaviour were unacceptable and unprofessional.

Six years on, the emerging allegations about Wallace’s conduct raise questions about whether executives - at the production company Banijay and the BBC - reacted appropriately.

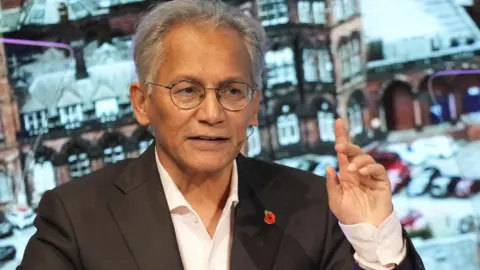

PA Media

PA MediaBut BBC News has not been told whether the BBC executives involved in Wallace’s shows were made aware of any complaints about him after 2018 and the conversation between him and Phillips. If they weren’t, there is some plausible deniability that they thought the issues raised had been sorted.

Then again, that defence may only go so far. There are wider questions about how much a TV executive should probe, if they are aware that rumours have begun to swirl.

Popbitch, the weekly celebrity newsletter that makes its way into the inboxes of most media executives, had run stories involving allegations about Wallace’s language and behaviour in the past, for example. When does the odd gossipy claim about talent misbehaviour become an issue bosses should take a look at?

Should more questions have been asked by the BBC after 2018?

Some have made the point that these types of scandals involving high profile TV presenters only seem to emerge when the media shines a light on them.

It’s only then, it is argued, that executives take action and launch an investigation. The claim is that before journalists get involved, the executives are more concerned with protecting the star, the show and their bottom line.

In light of Huw Edwards, the BBC launched a workplace review into preventing abuses of power. At the time, the BBC chair Samir Shah said there "continues to be a sense that powerful people 'get away with it'."

But for me, how the Wallace claims may have been handled isn’t entirely comparable to the Edwards scandal.

Huw Edwards was employed directly by the BBC, Wallace is contracted by production companies that make his shows and sell them to the BBC.

To put this in context, 326 independent companies made programmes for the BBC in the year 2023/4, accounting for 55% of the BBC’s TV hours.

I have picked up some frustration on the corporate side of the BBC that the corporation is taking criticism for a programme that it doesn't make.

A BBC insider told me it essentially bought a product from a third party and is now being held to account for the actions of staff in a different organisation.

My assessment is that if there were complaints - or claims of bad behaviour on set - the first port of call would have been the production company.

But that defence - that the BBC is at arm's length on this one - only goes so far. Audiences don’t make that distinction. In the end, they associate Wallace with the BBC, not a production company.

The damage rests at the BBC’s door.

The workplace review will aim to look at how to ensure that junior people with less power feel able to speak up, when a presenter is behaving badly. The director general Tim Davie has already said he’d like to ban the word "talent" for the BBC’s stars, to help end the hierarchies that can be a part of programme making when powerful, highly paid people with audience recognition are involved.

But, understandably, the review won’t have oversight of the independent sector. These are independent companies responsible for their own codes.

It would however be useful for the review to lay out what BBC processes are triggered when rumours begin to emerge about a particular star and what the BBC expects from its executives and indeed the production companies it buys programmes from.

Philippa Childs, the head of union Bectu, told Radio 4 on Wednesday "the time has come for the whole industry to come together and accept that there does need to be some independent scrutiny of how broadcasters [and] production companies work, to try and address this endemic problem".

The Wallace story may be a wake-up call for the production sector. For years, we’ve heard about junior staff feeling unable to speak truth to power in these sorts of scenarios.

Now, some women are refusing to stay silent. If the sector doesn’t get its house in order, it could be career limiting not just for high profile names but for executives as well.

At the heart of this latest story is a star accused of misbehaviour and splashed across the media daily. The presumption of innocence doesn’t always sit well with journalistic endeavours, but it should.

Gregg Wallace denies the allegations being made against him. The media doesn’t always play fair when it scents a scalp. But he is entitled to a fair and due process.

Africana55 Radio

Africana55 Radio