This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

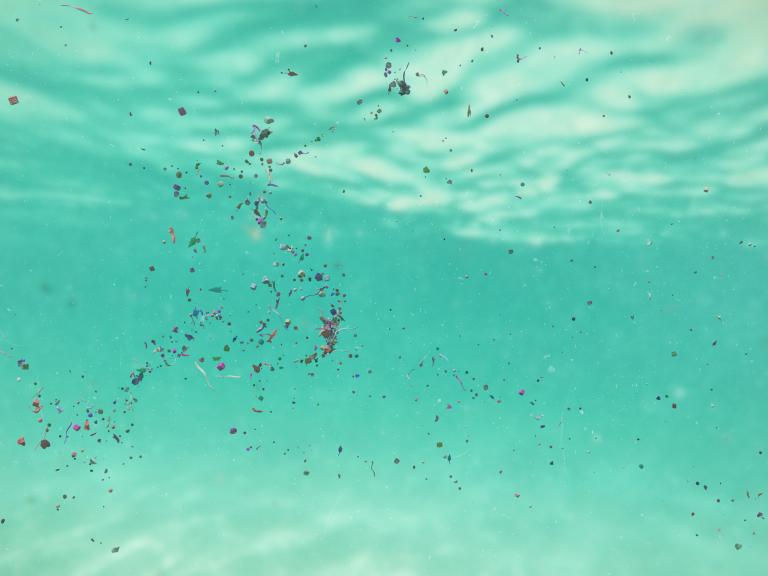

The vast majority of microfibres entering our oceans via clothes washing may not be synthetic fibres as previously thought, but are likely to be organic materials such as cotton and wool, a study has found.

Nonetheless, clothes washing still releases vast quantities of microfibres, whose impact on the marine environment is not fully understood.

Researchers from Northumbria University working in partnership with Procter & Gamble, makers of products such as Ariel, Tide, Downy and Lenor, found that 13,000 tonnes of microfibres, equivalent to two bin lorries every day, are being released into European marine environments every year.

The research team said it is the first major forensic study into the environmental impact of microfibres from real soiled household laundry.

The analysis revealed an average of 114 mg of microfibres were released per kilogram of fabric in each wash load during a standard washing cycle.

Scientists have speculated for some time that these microfibres may cause more harm than microbeads, which were banned from UK and US consumer products in recent years.

The researchers found that 96 per cent of the fibres released were natural, coming from cotton, wool and viscose, with synthetic fibres, such as nylon, polyester and acrylic accounting for just 4 per cent.

The scientists said the natural fibres from plant and animal sources biodegrade much more rapidly than the synthetic fibres. A previous study has identified that cotton fibres degraded by 76 per cent after almost eight months in wastewater, compared to just 4 per cent deterioration in polyester fibres over the same amount of time.

This means that natural fibres will continue to degrade over time, whereas petroleum-based microfibres plateaued and can be expected to remain in aquatic environments for a much longer period.

John Dean, professor of analytical and environmental sciences at Northumbria University, who led the study, said: “This is the first major study to examine real household wash loads and the reality of fibre release. We were surprised not only by the sheer quantity of fibres coming from these domestic wash loads, but also to see that the composition of microfibres coming out of the washing machine does not match the composition of clothing going into the machine, due to the way fabrics are constructed.

“Finding an ultimate solution to the pollution of marine ecosystems by microfibres released during laundering will likely require significant interventions in both textiles manufacturing processes and washing machine appliance design.”

The research team said using less energy intensive washing techniques reduced the amount of fibres lost from clothes. They said they achieved a 30 per cent reduction in the amount of microfibres released when they ran a 30-minute 15C wash cycle, in comparison to a standard 85-minute 40C cycle, based on typical domestic laundering.

Created with Sketch.

Created with Sketch.

1/41

Shane Gross /SWNS.com

2/41

Paolo Isgro /SWNS.com

3/41

Claudo Zori /SWNS.com

4/41

Alessandro Grasso /SWNS.com

5/41

Mok Wai Hoe /SWNS.com

6/41

Galice Hoarau /SWNS.com

7/41

Greg Lecoeur /SWNS.com

8/41

George Kuo-Wei Kao /SWNS.com

9/41

Tae Wook Kang /SWNS.com

10/41

Qing Lin /SWNS.com

11/41

Enrico Somogyi /SWNS.com

12/41

Jose Antonio Castellano/SWNS.com

13/41

Alessandro Buzzicheli/SWNS.com

14/41

Taeyup Kim/SWNS.com

15/41

Nicholas More/SWNS.com

16/41

Hakan Basar /SWNS.com

17/41

Enrico Somogyi/SWNS.com

18/41

Stephano Cerbai /SWNS.com

19/41

Wu Yung-Sen /SWNS.com

20/41

Hannes Klostermann /SWNS.com

21/41

Jay Clue /SWNS.com

22/41

Jules Casey /SWNS.com

23/41

Jenny Stock /SWNS.com

24/41

George Kuo-Wei Kao /SWNS.com

25/41

Greg Lecoeur /SWNS.com

26/41

Paolo Bausani /SWNS.com

27/41

Dave Johnson /SWNS.com

28/41

Celia Kujala /SWNS.com

29/41

Ferenc Lorincz /SWNS.com

30/41

Steven Kovacs /SWNS.com

31/41

Tobias Friedrich /SWNS.com

32/41

Fabien Michenet /SWNS.com

33/41

Pedro Carillo /SWNS.com

34/41

Yat Wai So /SWNS.com

35/41

Fabien Martinazzo /SWNS.com

36/41

Fabien Martinazzo /SWNS.com

37/41

Fabien Michenet /SWNS.com

38/41

Tianhong Wang /SWNS.com

39/41

Johan Sundelin /SWNS.com

40/41

Greg Lecoeur /SWNS.com

41/41

Paula Vianna /SWNS.com

1/41

Shane Gross /SWNS.com

2/41

Paolo Isgro /SWNS.com

3/41

Claudo Zori /SWNS.com

4/41

Alessandro Grasso /SWNS.com

5/41

Mok Wai Hoe /SWNS.com

6/41

Galice Hoarau /SWNS.com

7/41

Greg Lecoeur /SWNS.com

8/41

George Kuo-Wei Kao /SWNS.com

9/41

Tae Wook Kang /SWNS.com

10/41

Qing Lin /SWNS.com

11/41

Enrico Somogyi /SWNS.com

12/41

Jose Antonio Castellano/SWNS.com

13/41

Alessandro Buzzicheli/SWNS.com

14/41

Taeyup Kim/SWNS.com

15/41

Nicholas More/SWNS.com

16/41

Hakan Basar /SWNS.com

17/41

Enrico Somogyi/SWNS.com

18/41

Stephano Cerbai /SWNS.com

19/41

Wu Yung-Sen /SWNS.com

20/41

Hannes Klostermann /SWNS.com

21/41

Jay Clue /SWNS.com

22/41

Jules Casey /SWNS.com

23/41

Jenny Stock /SWNS.com

24/41

George Kuo-Wei Kao /SWNS.com

25/41

Greg Lecoeur /SWNS.com

26/41

Paolo Bausani /SWNS.com

27/41

Dave Johnson /SWNS.com

28/41

Celia Kujala /SWNS.com

29/41

Ferenc Lorincz /SWNS.com

30/41

Steven Kovacs /SWNS.com

31/41

Tobias Friedrich /SWNS.com

32/41

Fabien Michenet /SWNS.com

33/41

Pedro Carillo /SWNS.com

34/41

Yat Wai So /SWNS.com

35/41

Fabien Martinazzo /SWNS.com

36/41

Fabien Martinazzo /SWNS.com

37/41

Fabien Michenet /SWNS.com

38/41

Tianhong Wang /SWNS.com

39/41

Johan Sundelin /SWNS.com

40/41

Greg Lecoeur /SWNS.com

41/41

Paula Vianna /SWNS.com

Furthermore, they found the more water used in each wash, the more fibres were stripped from the clothes.

“If households changed to cooler, faster washes, they would potentially save 3,813 tonnes of microfibres being released into marine ecosystems in Europe,” the study said.

The team also noted new clothes release more microfibres than older clothes.

They said the research “provides evidence for appliance manufacturers to introduce filtering systems into the design of machines and develop approaches to reduce water consumption in laundry.”

The paper, Microfiber Release from Real Soiled Consumer Laundry and Impact of Fabric Care Products and Washing Conditions is published in the journal Plos One.

Africana55 Radio

Africana55 Radio