This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

In August, Donald Trump reportedly asked top national security officials to consider using nuclear bombs to weaken or destroy hurricanes. Now, one member of Congress wants to make it illegal for Mr Trump, or any president, to act on this idea, which experts say would be both ineffective and extremely dangerous.

On 1 June, Sylvia Garcia, Democratic representative for Texas, introduced the Climate Change and Hurricane Correlation and Strategy Act, a bill that explicitly prohibits the president, along with any other federal agency or official, from employing a nuclear bomb or other “strategic weapon” with the goal of “altering weather patterns or addressing climate change”.

Ms Garcia said that the bill was drafted as a direct response to last year’s report that Mr Trump has floated the idea of nuking hurricanes. Mr Trump denied ever making such a suggestion in a tweet shortly after Axios published the initial report.

The bill, which has no co-sponsors and no hearing date, appears unlikely to make it out of committee anytime soon. It has been referred to three committees: Armed Services; Energy and Commerce; and Science, Space and Technology.

With no companion bills in the Senate, the chances of it appearing on the president’s desk, much less being signed into law, are slimmer. But after hearing Mr Trump’s alleged comments on nukes and hurricanes and researching the issue further, Ms Garcia felt she had to at least get the idea of a ban on using nuclear weapons to disrupt the weather on the table.

“When I heard our president suggest that we needed to launch a nuclear weapon to disrupt a hurricane, my first thought was that’s a really dumb idea,” Ms Garcia said, in an interview with The Washington Post. “When we did the research, we found that others have thought of that idea before.”

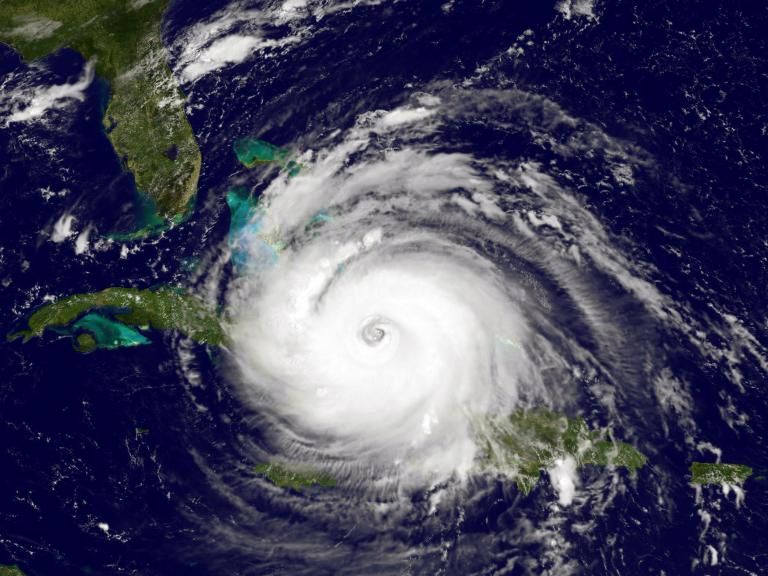

The bill comes at the start of the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season, which is off to a quick start, with Tropical Storm Cristobal, the earliest-recorded third named-storm of any season, striking Louisiana on Sunday. The season is expected to bring above-average storm activity, with 14 to 19 named-storms, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOOA).

According to James Fleming, a professor at Colby College and author of Fixing the Sky: The Checkered History of Weather and Climate Control, people have been discussing the possibility for almost as long as nuclear weapons have existed.

In October 1945, Vladimir Zworykin, associate research director at Radio Corporation of America, suggested that if humans had technology to perfectly predict the weather, military forces could be sent out to disrupt storms before they formed, perhaps using atomic bombs. That year, Unesco director Julian Huxley spoke at an arms control conference in Manhattan, where he discussed using nuclear weapons for “landscaping the Earth” or dissolving the polar ice cap. In a 1961 speech at the National Press Club, US Weather Bureau head Francis Reichelderfer said he could “imagine the possibility someday of exploding a nuclear bomb on a hurricane far at sea”, according to a 2016 report by National Geographic.

The United States even conducted several near-space experiments using nukes, including Operation Argus, a 1958 field test in which the military and the Atomic Energy Commission detonated atomic bombs more than 100 miles above the South Atlantic Ocean in an ill-conceived effort to induce artificial radiation belts in Earth’s magnetic field. According to Mr Fleming, the Argus tests, along with subsequent high-altitude nuclear detonations, helped “fuel discussions” leading to the Partial Test Ban Treaty of 1963, which prohibits atmospheric nuclear weapons tests.

While nuking a hurricane in an attempt to destroy or weaken it would probably cause an international uproar, the Partial Test Ban Treaty would not prohibit the president from doing so. There is no domestic law or international treaty that would prohibit such an action, according to Scott Sagan, a professor of political science at Stanford University.

“It would be a stupid thing to do, but it would not be an illegal thing to do,” Mr Sagan said. He said test bans would not cover the actual use of a nuclear weapon against a perceived threat to the United States. In such circumstances, the president has sole authority to use nuclear weapons.

Hurricane experts have long maintained that detonating a nuclear device in a hurricane would have little effect on it, according to NOOA. As the agency explains on its website, the energy released by nuclear weapons pales in comparison to the energy released by a typical hurricane, which NOAA describes as comparable to a 10-megaton nuclear bomb exploding “every 20 minutes”.

Even detonating multiple nuclear bombs inside a hurricane is unlikely to disrupt the storm, though the radioactive fallout released downwind could have catastrophic effects for people and the environment.

“We don’t have any knowledge on how far that fallout might spread,” said Michael Jacquari Smith, a recent meteorology graduate from Jackson State University who has investigated the issue. “It’s just like dealing with Covid-19 – we don’t know much about it.”

“It was a bad idea when [the NOAA] wrote this FAQ,” said Phil Klotzbach, a meteorologist and tropical cyclone expert at Colorado State University, “and it’s still a bad idea”.

In addition to prohibiting the president from attempting to alter the weather with nukes, Ms Garcia’s bill calls for the White House, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the NOAA to issue five annual reports to Congress on “ways to combat increasing hurricane activity due to warming oceans from climate change”, as well as a “a one-time scientific explanation and analysis on the use of nuclear bombs to alter severe weather, such as hurricanes”.

This explanation would explore the health and environmental risks of deploying nuclear weapons on hurricanes, the radioactive fallout, and “how such use would or would not address the systemic issues and challenges of hurricanes”.

Climate studies show that warming seas and air temperatures are making hurricanes more damaging by increasing their rainfall output and favouring higher-end, “major” storms of Category 3 intensity or greater. Scientists have also been seeing a small increase in storms that rapidly intensify from weak to major hurricane status, which is enabled by warm sea surface temperatures, among other factors.

Ms Garcia’s district on the eastern side of Houston was heavily impacted by flooding during Hurricane Harvey in 2017, a storm that featured extreme rainfall totals that scientists eventually tied in part to climate change.

Mr Klotzbach said the bill’s call for annual reports on hurricanes and climate change seemed redundant, given that many reports on the topic already exist. But he felt that a modelling study investigating the effects of dropping a nuclear bomb on a hurricane could be useful, if only to help scientists debunk the idea in the future.

Mr Fleming, of Colby College, said that the new bill seemed like “an overreaction to an off-the-cuff comment, a nonexistent threat”.

Axios’s report noted that Mr Trump raised the idea not once, but at multiple points in time, including with top national security and intelligence aides.

Kerry Emanuel, a hurricane expert at MIT, sees things a bit differently.

“If we have a leader who would contemplate using a nuclear weapon on a hurricane,” he said, “we have a much more extensive and serious problem than could be covered by a specific bill like this one”.

The Washington Post

Africana55 Radio

Africana55 Radio