This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Intense wildfires are sweeping across the Arctic Circle, surpassing the numbers recorded in June 2019, amid "exceptionally high" temperatures in the Siberian region.

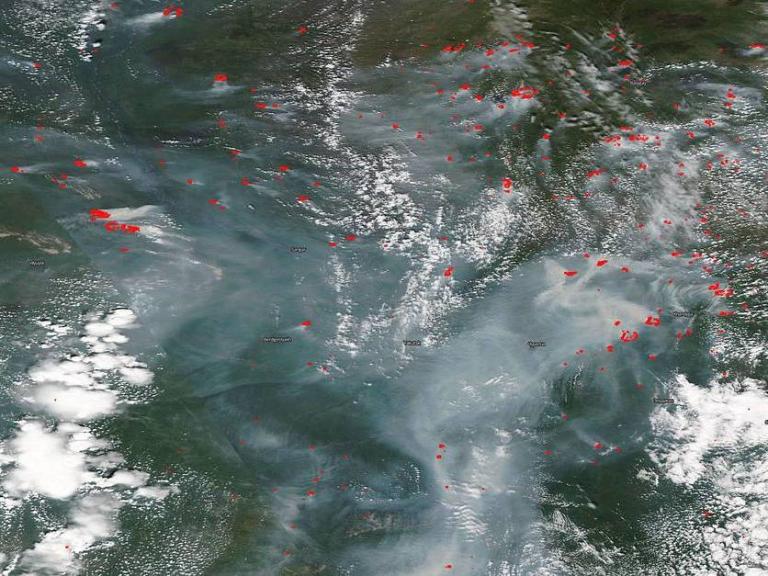

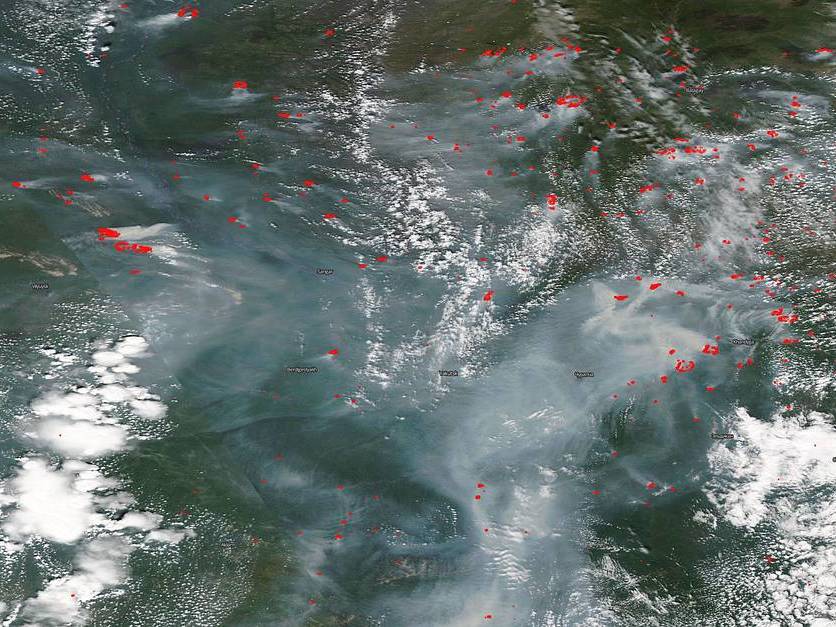

NASA satellite images revealed fires dotted across the landscape and billowing clouds of smoke which scientists say will "catch a ride on the jet stream to other areas of the globe".

An estimated 3.4million acres are burning - an area about half the size of Massachusetts - according to Russia's forest fire agency. Around 1.1m acres were ablaze at the end of June, meaning that the fire zone has tripled in roughly a week.

The number of wildfires has been on the rise since mid-June in the neighbouring regions of the Sakha Republic and Chukotka Autonomous Oblast, along with parts of Alaska and the Yukon Territories.

The fires burn unabated due to the fact that Siberia is largely inaccessible and sparsely populated. The blazes are fuelled by the boreal forest, which wraps around the top of the Northern Hemisphere, peat bogs and tundra, which produce more smoke than trees or grass when they catch fire.

Although Siberian fires have been seasonal, NASA scientists pointed out that the peat fires have the potential to smoulder underground during winter and reappear in the spring, a phenomenon known as "zombie fires".

Boreal forest, peat bogs and tundra all have higher concentrations of carbon which spew carbon dioxide (CO2) into the atmosphere when burned.

The fires have led to the highest-estimated emissions since records began 18 years ago, according to the EU's Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS). In June, an estimated 59 megatonnes of CO2 were released into the atmosphere, an increase from June 2019’s 53 megatonnes.

CAMS Senior Scientist and wildfire expert, Mark Parrington, said: “What is remarkable with these fires in Siberia is the striking similarity with what we saw over the same period of last year in terms of both the area affected and the scale of the fires. Last year was already by far an unusual, and record, summer for fires in the Arctic Circle in our Global Fire Assimilation System dataset, which goes back to 2003.

"This year has evolved in a very similar way and if it continues to progress like last year, we could see intense activity for the next few weeks.”

Higher carbon emissions cause temperatures to rise and this year, Siberia saw a new temperature record of 100.4F (38C). Historic heatwaves lead to more frequent fires which spread rapidly. This has been coupled with stronger winds which drive wildfires.

The Siberian Arctic is also experiencing record high temperatures for the second year in a row.

The EU observation program, Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S), reported on Tuesday that average temperatures last month were equivalent to June 2019’s worldwide record, with “exceptionally high” temperatures in Arctic Siberia.

In June, and across the last 12 months, Siberia is the region with the largest temperature anomalies, C3S reported. In the region, average temperatures climbed 10C (50F) above normal for June.

C3S director at the European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecast (ECMWF), Carlo Buontempo, said that understanding the cause of the record temperatures was a complex task because many contributing factors were at play.

He said: “Siberia and the Arctic Circle in general have large fluctuations from year to year and have experienced other relatively warm Junes before.

“What is worrisome is that the Arctic is warming faster than the rest of the world. Western Siberia experiencing warmer-than-average temperatures so long during the winter and spring is unusual, and the exceptionally high temperatures in Arctic Siberia that have occurred now in June 2020 are equally a cause for concern.”

Climate variability was also noted across Europe where temperatures were far above average in the north but below average in the south. Overall, it was the joint second warmest June recorded in Europe.

Africana55 Radio

Africana55 Radio