This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Lieutenant General Russel Honoré, the revered Army commander who led evacuations during Hurricane Katrina, told The Independent how he fears that refineries and petrochemical plants which line the Gulf coast are unprepared for increasingly extreme weather driven by the climate crisis, as the region faces a vast recovery operation in the wake of Hurricane Laura this week.

“I don’t think they’re prepared for what we see now with rising sea levels and warm, extended ocean heat that makes the hurricanes stronger,” he said. “I think we need to go back and look at how we make our industries more resilient.”

This Saturday marks the 15th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, which hit the Gulf Coast in 2005, and was the costliest storm in US history. An estimated 1,800 people died but the true death toll is unknown because many people were unaccounted for. The devastation wreaked was not felt equally: A 2005 study found that in Orleans Parish, New Orleans, the adult mortality rate among black residents was 1.7 - 4 times higher than among white citizens.

Almost to the day of the previous disaster, Hurricane Laura made landfall as a category-4 storm in Louisiana on Thursday, pummelling the petrochemical corridor along the Gulf Coast with storm surges and ferocious winds leading to fears over potential toxic fallout. At least ten people are dead and the extent of the damage is unknown as some regions remain cut off.

As first light broke on Friday, a massive fire was visible at a Lake Charles chlorine plant, blanketing the nearby town of Westlake in thick, black smoke. Residents were told to shelter in their homes and close doors and windows while crews battled the blaze until the evening, after initially having trouble reaching the site due to downed trees and power lines.

“The chlorine plant we can see and smell it,” Lt. Gen Honoré said. ”Right now, I’m worried about what I can’t see and smell. We have to find all those places and start the mitigation work. The incident in Lake Charles is significant because it’s blocking the interstate which is critical to recovery in the Calcasieu, Cameron and Beauregard parishes. There’s devastation north and south, in both directions.”

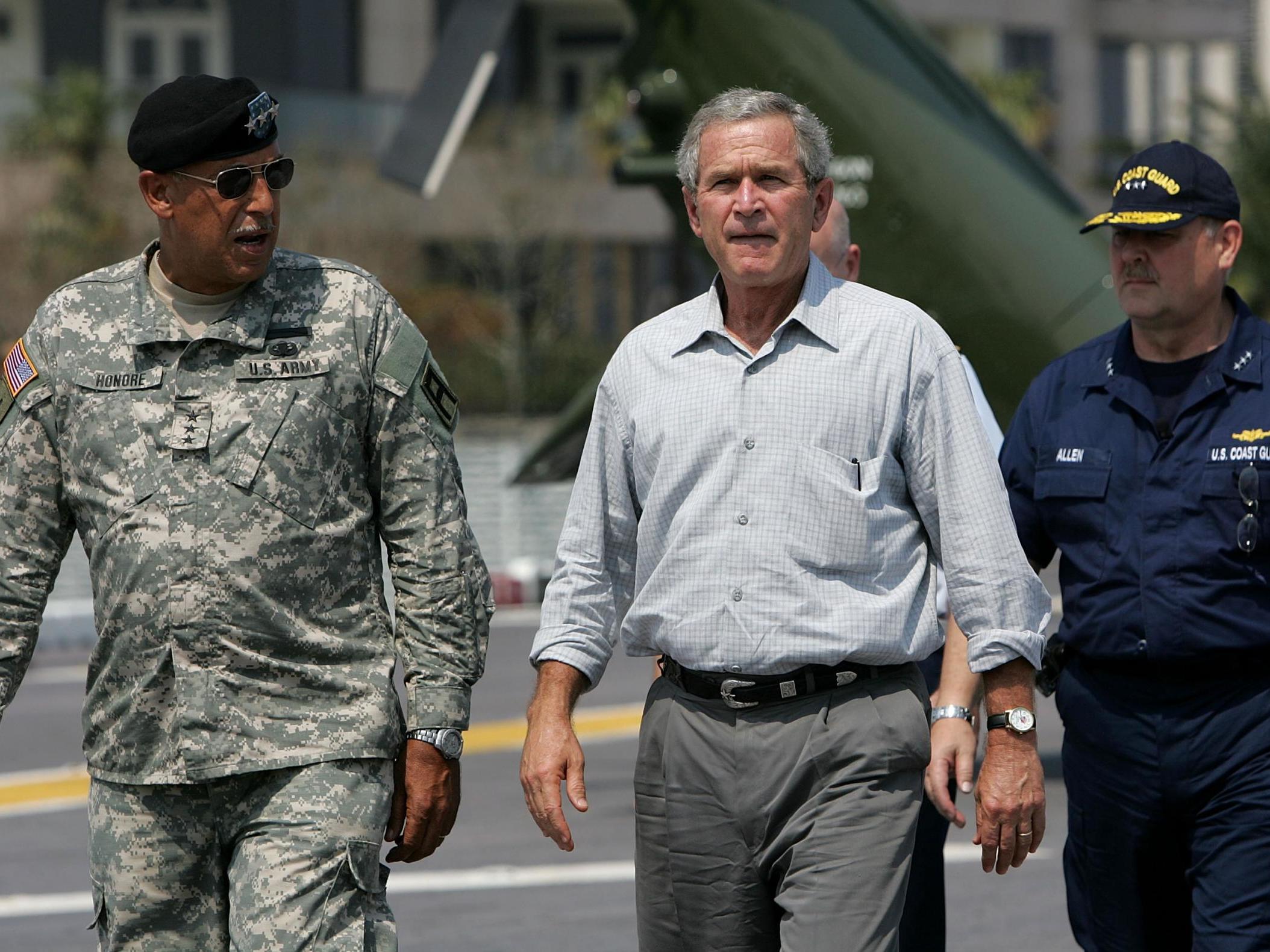

Lt. Gen Honoré holds near mythical status in Louisiana. He’s known in parts as the “Category-5 General” after his command of the Joint Katrina Task Force which led the evacuation of 16,000 people from the New Orleans Superdome during the disaster. Former New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin, dubbed him the “Black John Wayne”, adding that he “came off the doggone chopper, and he started cussing and people started moving”.

Lt Gen Honoré, who also commanded the taskforce for Hurricane Rita that hit Louisiana a month after Katrina, spoke about what had – and hadn’t – been learned in the interim years.

“Anytime you have a major disaster like this, it creates a lot of stress on people,” he said. “And most of the time it makes the government look stupid. People have a need to get back to their lives and the government is working off checklists and procedures.

“From Katrina and Rita, we learned that we needed to have a better way to respond to people’s needs to get them back in their homes, but not much has changed since then.” He noted that FEMA’s Individual Disaster Assistance, created in the wake of Katrina, “works well” but efforts can be slowed when people are displaced from their homes and Internet is cut off.

The coronavirus pandemic, which has hit particularly hard in Louisiana, would only complicate recovery operations from Laura. “All the people you have to bring in from other parts of the country have to comply with Covid rules – wearing masks and washing hands, when there’s no clean water. When you lose electricity, that is a disaster unto itself,” he added.

Some 200,000 people in Louisiana are currently without access to water and more than 700,000 homes and businesses have no power, the Weather Channel reported.

After retiring from the US Army in 2008, Lt Gen Honoré mobilised his “Green Army”, an alliance of community and environmental groups fighting toxic pollution in the state, with much of it centered along the Gulf Coast. This weekend, he planned to travel to coastal parishes to assist with recovery efforts and assess the damage.

“The downside of putting so much industry along shipping channels is that it is in flood zones,” he said. “But industry is driven by profits which increase because they’re on shipping channels. The people who own the industry don’t live there, so they’ll take that risk with other people’s lives.

“When something bad happens – accident, explosion, manmade, caused by a storm – the people who live here, they live with the consequences. Not the hedge fund in New York, or a company in California or Japan or elsewhere in the world.”

He said that it was necessary to build back stronger but in the face of more frequent and intense storms “it’s a constant battle of survival.”

A study earlier this year by Jupiter Intelligence, a company which provides data analytics to help companies prepare for disasters, found that three major petrochemical facilities located on the Gulf near Houston are “highly vulnerable to extreme flooding from storm surge, sea-level rise, and prolonged precipitation caused by climate change”.

“The study concludes that the costs of climate-related risk could rise by as much as 800 percent by 2030,” the report found.

The people living closest to heavy concentrations of industries, in “fence-line” communities, are typically low-income and often largely communities of colour.

Wilma Subra, a Louisiana chemist and environmentalist who works with local people to combat toxic chemicals, told The Independent: “Every time we have a hurricane, it seems to impact an industrial facility. In this case, it was a lot of smoke and emissions from the BioLab facility that went into Westlake, which is primarily an African American community.

“There are communities right up against the fence line at these industrial facilities, usually minority communities. They are the most vulnerable and the first to be impacted if any release occurs.”

The Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality told AP that it did not immediately detect chlorine releases from the BioLab plant, which makes swimming pool chemicals.

BioLab’s corporate parent said the plant had been shut down and evacuated ahead of the storm, and no plant employees were injured. State police said they knew of no reports of injuries, including exposure to hazardous fumes.

Ms Subra said that it was yet unclear if any chlorine gas had negatively impacted the surrounding community. “If you’re exposed to chlorine and you breathe it in, it damages the tissue of your lungs. Those tissues do not recover,” she said.

The chemical plant fire came at a perilous point for the local community. Downed electricity and internet in the area may have made it difficult for people to receive the emergency shelter-in-place alerts, Ms Subra said. Similarly any sirens going off may have been difficult to hear in howling wind and rain.

Additionally, the official advice to seal doors and windows is not as easy as it sounds in many homes close to industrial facilities which may be made from less resilient materials than bricks and mortar.

“Even if you turn off air conditioning and close doors and windows, emissions from the outside can still make it into homes,” Ms Subra said. Add to that the soaring temperatures this month in US southern states – and you could be sheltering at home in 110-120F temperatures.

“The pandemic may have also kept people from evacuating – either for health or financial reasons. “There may have been reluctance to go to a centre where everybody was squeezed in, sitting on cots, particularly if you’re an older person and more vulnerable to the pandemic. And the state wasn’t opening up all these shelters because of those issues,” Ms Subra added.

Three years ago, record rains from Hurricane Harvey inundated Houston’s refineries, storage tanks and chemical plants, unleashing dozens of toxic spills into surrounding communities’ air, land and water. This week, state and federal aircraft were heading into the air over the battered Louisiana coast, looking for signs of any other industrial damage or releases from Laura.

Michael Brown, Earthjustice staff attorney with the fossil fuels program, told The Independent that in 2005, Hurricanes Katrina and Rita created the largest ever oil spill in coastal Louisiana after Exxon Valdez (and five years before the Deepwater Horizon oil platform explosion led to the largest spill in history).

“We saw failures of these industrial systems but also failures of government to address the problem in a serious way,” he said, noting that 15 years on, the National Resource Damage Assessment process had not yet concluded and “industry hasn’t been held accountable”.

Mr Brown added: “Since Harvey, the petrochemical and oil and gas industry have had a massive build-out plan for the Gulf Coast. They’ve been adding more infrastructure, including in Lake Charles, intending that these plants will exist for 30-50 years without addressing the increasing climate risk they are going to be facing from storms like we saw this week.”

Environmental damage was not just felt in the aftermath of Laura. The Houston Chronicle reported on Thursday that Texas refineries and chemical plants planned to release four million pounds of air pollution in Gulf Coast facilities before Laura hit.

Mr Brown said that these huge releases of emissions were “a really big concern and broadened the impact area”.

Alicia Cooke with 350 New Orleans, a global non-profit which campaigns against fossil fuels, said: “Laura reminds us of the danger of fossil fuel reliance from two perspectives: not only is she strengthened by climate change, but we also see her path cutting straight through a major petrochemical hub along the Louisiana/Texas border, with potential for great environmental catastrophe.

“When we rely on a fossil fuel economy, we rely on the integrity of oil and gas infrastructure, which has become increasingly vulnerable as storms continue to strengthen year after year.”

Wires contributed to this report

Africana55 Radio

Africana55 Radio