This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

And yet in a key moment on Wednesday she appeared to do precisely that: refusing to say that climate change is scientific fact, but rather “a very contentious matter of public debate”, during questioning by committee member and Democratic VP nominee Senator Kamala Harris.

“I will not express a view on a matter of public policy, especially one that is politically controversial,” Judge Barrett said.

“You know, I”m certainly not a scientist,” she said a day earlier. “I mean, I’ve read things about climate change. I would not say that I have firm views on it.”

Greta Thunberg, climate activist, tweeted: “To be fair, I don’t have any ‘views on climate change’ either. Just like I don’t have any ‘views’ on gravity, the fact that the earth is round, photosynthesis nor evolution.

“But understanding and knowing their existence really makes life in the 21st century so much easier.”

Brett Hartl, government affairs director at the Center for Biological Diversity, said: "It is a typical conservative, right-wing view that scientific reality is something that you can have an opinion about."

Despite a slim judicial record on environmental issues, Judge Barrett's remarks illuminate how such cases might fare in the land’s highest court, on the verge of a 6-3 conservative majority.

“I think it's likely to be a court that is significantly more hostile to environmental regulation, even more than the current court,” Professor Ann Carlson, faculty co-director of the Emmett Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at UCLA School of Law told The Independent.

Scientists say that we have around a decade to make meaningful cuts to emissions and bring climate change under control, or the planet will face even more severe impacts than we are already witnessing.

Robert Percival, director of the environmental law programme at the University of Maryland, told Grist that “environmentalists are facing a real minefield ahead”.

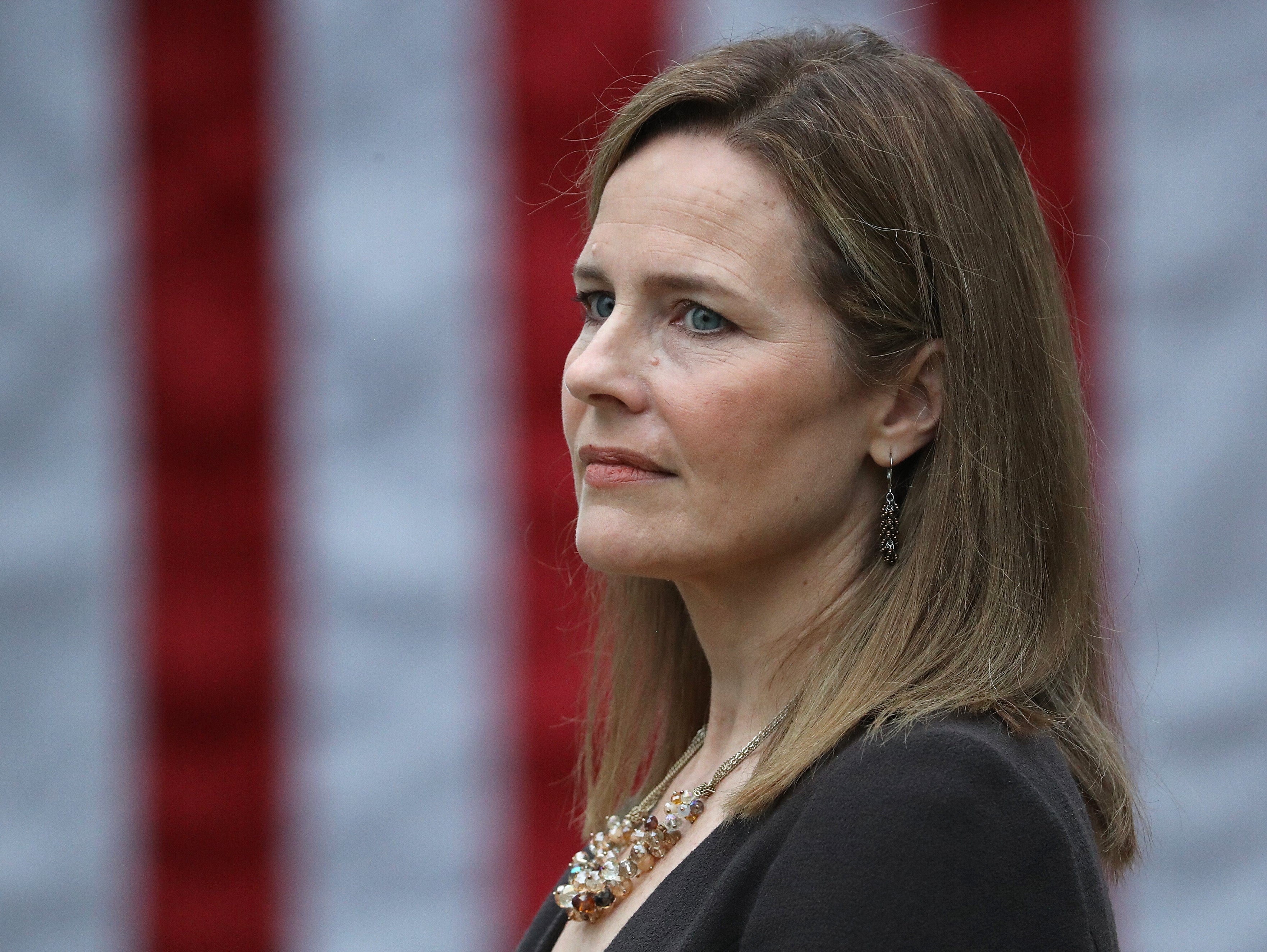

How might the 48-year-old Judge Barrett's lifetime Supreme Court appointment shape the US’s ability to tackle climate change in the crucial decades to come, and what paths to meaningful action remain?

'No standing' for public interest groups, states

To bring a case before the Supreme Court, the plaintiff must have "standing” or in other words, have suffered injury.

It was a ruling by the late liberal Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who Judge Barrett will replace, that opened the door for environmental groups and states to seek justice on environmental issues, and not be dismissed before reaching the highest court.

In 2000, Justice Ginsburg wrote that Friends of the Earth had “standing” against Laidlaw Environmental Services because of their “reasonable concerns” about industrial pollution.

“Justice Ginsburg wrote a tour de force in that opinion,” Harvard Law Professor Richard Lazarus told PRI, saying that she laid the foundation for Massachusetts v Environmental Protection Agency, widely seen as the most significant environmental case ever to reach the Supreme Court.

The landmark case was won 12 states and a handful of cities after the court ruled that it was the government’s responsibility to address climate pollution. But it was a narrow victory, 5-4, and only one of the justices in the majority still sits on the court.

On the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals, where Judge Barrett was appointed in 2017 after President Trump’s nomination, she has taken a narrow view of who can bring cases over environmental damages, “writing the majority opinion in at least two cases denying opponents standing in court”, the Washington Post reported.

Additionally, having a case reach the Supreme Court has X-Factor-like odds: only about 1 per cent of roughly 8,000 cases submitted each year. They are selected by a “Rule of Four” justices but with the court tipped largely right, it could have serious implications as to which ones even make it through the doors.

As Judge Barrett has said that she has no “firm views” on climate change, it is hard for some to imagine how she would be convinced that a case involving the issue should be taken up by the court.

Mr Hartl said: “If [Judge Barrett] doesn’t believe that people are actually injured by climate change, cases like Massachusetts v EPA will be lost before you even get to the merits. The court will not be open to hearing those sorts of cases in the first place. That’s a huge problem.”

Making it harder for states and environmental groups to go to court in the first place, Mr Hartl says, means "giving additional power to other sorts of groups, like corporations".

If President Trump wins re-election, he will likely continue dismantling environmental rules and policies. If environmental groups and states lose the opportunity to sue, there would be little to stop the rollbacks.

Shutting down executive action and stifling agencies

If elected, Joe Biden has promised a $2trillion plan to tackle climate change and a "demand that Congress enacts legislation in the first year” to ensure net-zero emissions by 2050. But a Senate that remains in Republican control suggests little hope of passing that sweeping agenda.

Professor Carlson points to the Clean Air Act (CCA) as a next best option but this is far from without pitfalls and would “invariably invoke a challenge”.

"The current composition of the court already threatens EPA authority to regulate GHGs aggressively under the Clean Air Act,” she said, noting that Justice Brett Kavanaugh, another Trump appointee, has previously been extremely sceptical that the act even covers emissions.

“Kavanaugh takes on increasing importance, particularly on environmental questions. I think he becomes the centre of a very conservative court,” Prof. Carlson said.

“Everything I can tell about Amy Coney Barrett is that she is cut out of the same Federalist Society cloth. Her answers on climate change in the past two days were signals."

She added that, in her opinion, “the addition of Judge Barrett pretty much guarantees that any attempt by EPA, without some congressional action, to aggressively regulate (GHG) emissions is going to be struck down.”

The Federalist Society is a conservative organisation advocating for a “textualist” or originalist interpretation of the US Constitution, which Judge Barrett adheres to.

At the hearing, she explained that "I interpret the Constitution as a law, that I interpret its text as text, and I understand it to have the meaning that it had at the time people ratified it," Barrett said. "So that meaning doesn’t change over time and it’s not up to me to update it or infuse my own policy views into it.”

Mr Hartl noted: “At the end of the day, originalism and textualism are really just a very narrow view on progress. It’s basically saying the people who wrote the Constitution back in an era when there wasn’t even electricity should forever lock us into our views and our government."

In his opinion, Mr Hartl said, textualism "is a convenient excuse to accomplish a goal that is ideological”.

Of major concern, Prof Carlson says, is a little-known legal theory called the “non-delegation doctrine”, which has lain dormant since the 1930s New Deal-era, but which all five conservative justices have expressed interest in reviving. Judge Barrett has also indicated support for the doctrine in writings.

The theory holds that Congress cannot delegate its legislative powers to administrative agencies, and laws can be quashed if they seem to be designated too much power.

For example, while the Supreme Court ruled in favour of EPA plans to regulate GHG emissions from industry back in 2014, the agency itself admitted that the Clean Air Act, established in the 1960s, doesn’t easily lend itself to regulating CO2.

In the past, Congress has tended to paint in broad brushstrokes like with the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts.

Prof Carlson noted that the Supreme Court could make the argument that because "Congress hasn’t spoken about GHGs in the Clean Air Act, even though it covers air pollutants very broadly, it is therefore an unconstitutional delegation of legislative power to agency”.

She added: “If Congress cannot delegate power to administrative agencies to implement statutes, it could really destroy a whole apparatus that grew up in the post-war era.”

If November brings a blue wave and Democrats become the Senate majority, there is more chance of Congress passing legislation to limit emissions and it being on "firmer ground in the Supreme Court”.

But Prof Carlson added that "Congress will need to be careful about the non-delegation doctrine” and pass a law that is “very clear and direct”, to prevent a court striking it down.

Paths for climate action

While passing a climate bill in Congress is the best chance of success, it’s not the only option.

“In theory, laws on the books are still on the books,” Mr Hartl said. “And Congress is free to pass additional legislation. There are still lots of tools to address climate and environmental problems even in a world with a 6-3 conservative majority.

“The challenge is to find legal action that is less at the fringe and not push the boundaries when you have a court that is hostile to boundaries.”

Prof Carlson said that it remains to be seen how far the court moves to the right. Conservative Chief Justice John Roberts has joined with the liberal wing in some recent rulings but with such a tip in the court, his power is diluted.

And then there’s the question of whether Democrats will add more seats to the court, something Mr Biden and Sen Harris have been coy about.

“There’s so many moving parts,” Prof Carlson said.

Mr Hartl noted that Democrats have been “a little bit naive” compared to how Republicans have approached the courts. A study this year found that the GOP has been laser-focused in its strategy of packing supreme courts at state level too.

In 2014, after President Obama’s climate change law was blocked by Congress, he pivoted to the EPA, creating the Clean Power Plan which set the first-ever limits on power plants, the largest source of carbon pollution in the US.

The standard set by Massachusetts v EPA means it should have succeeded. But around two dozen, largely Republican leaning states sued to block it, a move that was backed by the Supreme Court. The regulation withered until the end of Obama’s presidency and President Trump replaced it with a watered-down version.

Mr Hartl said the Clean Power Plan has suffered from Democrats’ ultimately flawed calculus that industry and Republicans "wouldn’t fight to the death and litigate”.

“Industry fought everything that Obama did as if it were the worst thing ever,” Mr Hartl said. Making meaningful environmental progress ”will require a change in thinking about how to anticipate what the court will do".

He added: "Frankly because of the likely challenge to standing, it’s going to be harder for the advocacy groups and states.

"So it’s going to be incumbent upon a potential Biden administration to do the right thing from the outset, even if it’s politically difficult.”

Africana55 Radio

Africana55 Radio