This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

The first Brazilian striker to play for Barcelona scored more times than Ronaldo and Romario combined, had a better goals-to-games ratio than Neymar or Rivaldo and got the goal that knocked Real Madrid out of the European Cup for the very first time - before crossing that bitter divide two years later.

For Brazil, he holds a goalscoring record that Pele never matched, yet was prohibited from playing at the 1958 World Cup. As a manager, he led 16 different teams, including Iraq, where he worked alongside Saddam Hussein's son.

Now aged 87, Evaristo de Macedo Filho looks back on a remarkable career in football - and the extraordinary goal that still defines him as a Barca legend, despite everything that followed.

Born in 1933, Evaristo grew up in northern Rio de Janeiro, far from the city's famous beaches and postcard views. He played football just for fun on the streets, but that changed after he tagged along to a friend's trial at local club Madureira in 1950.

The coaches asked him to make up the numbers and handed over a pair of old boots. Despite the footwear being so tight his toes curled, the 17-year-old impressed and was asked to return the following day.

Within two years, Evaristo had scored 18 goals in 35 games for Madureira, including one against national team goalkeeper Castilho's Fluminense at the Maracana - the same fabled stadium he had squeezed inside to watch the 1950 World Cup final, alongside 200,000 others.

His performances as an amateur for Madureira led to a call-up for the 1952 Olympic Games in Helsinki, where Brazil scored nine goals in three games before succumbing to an experienced Germany side in the quarter-finals.

The small band of Brazilians, including future two-time World Cup-winners Vava and Zozimo, returned home with enhanced reputations and contract offers from clubs around the country. Evaristo, a lifelong Flamengo fan, got the call he wanted most. Over the next three years he helped his boyhood club to three successive Rio State Championships.

"Flamengo was always the team of my heart," Evaristo tells BBC Sport from his home in Rio de Janeiro. "I grew up watching them with my uncle so there was only ever one team for me. I had offers from Vasco da Gama and Fluminense, but Flamengo gave me so much and I'm eternally grateful."

Remembered as a physical and ruthless forward, many of Evaristo's goalscoring records still stand to this day.

Among his 103 goals in 191 games for Flamengo are a quintet of strikes during a 12-2 win over Sao Cristovao - the biggest win in Maracana history. Similarly, at the 1957 South American Championships, playing for Brazil alongside the legendary Garrincha and Nilton Santos, he scored five in a 9-0 demolition of Colombia, a feat unmatched even by Pele.

It was while playing for Brazil, during qualifying for the 1958 World Cup, that Evaristo's path diverted from Flamengo.

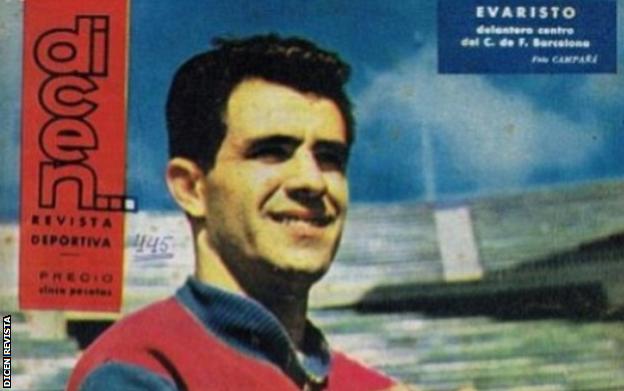

Barcelona were in a period of rebuilding and Josep Samitier, the club's technical secretary, had flown to South America in search of a striker. Aware Italian teams were also scouting, he made Evaristo's father a proposal that the player would later call "impossible to turn down". Spanish media reports suggest it was in the region of 700,000 pesetas, or £6,000 a year (about £140,000 today).

"Life in Barcelona was normal, super quiet, and never problematic - it felt a lot like life in Rio de Janeiro at that time," recalls Evaristo, who returned briefly to Brazil after three months to marry his childhood sweetheart, Norma.

"Each player had a fan club so we were in demand, but not like it is today because there were no mobile phones. The club provided me with everything: a house, a Mercedes, the lot. They also fully trusted us, so we could go out and eat paella, drink Spanish wines. It was marvellous."

Content off the pitch, Evaristo quickly adapted to life on it. He played and scored in the first official match at the Nou Camp in September 1957. Six months later, he became the first player to get a hat-trick there. And in the following season he repeated the feat, scoring three against European champions Real Madrid en route to Barcelona's first La Liga title in six years.

A match report published in Hoja del Lunes de Barcelona describes him as a "battering ram" who played like the ball was "glued to his feet".

The club's official website describes Evaristo as "one of the best foreign signings Barca ever made" and a "typically silky skilled Brazilian with a deadly instinct in front of goal, a terrific shot with either foot, a powerful head, and the kind of speed and courage that made him an ever-present in the Barca first team for five years".

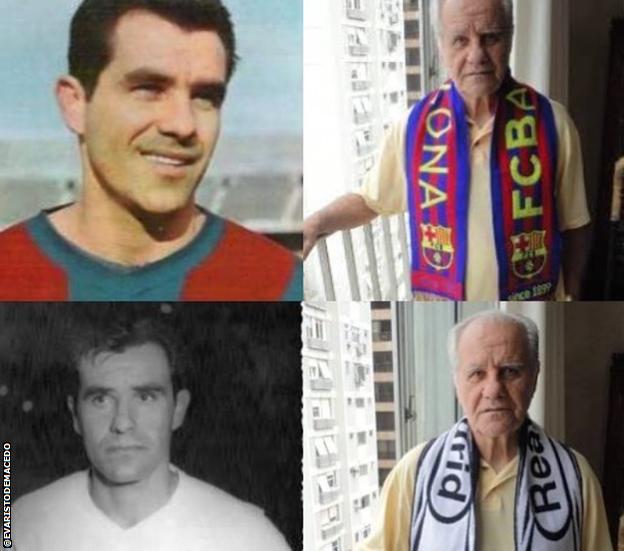

In a side managed by Helenio Herrera, playing alongside Laszlo Kubala and Luis Suarez, Evaristo won two league titles, a Copa del Rey, and the Fairs Cup - the precursor to the Uefa Cup - twice. Barcelona's statistics department relayed by email that in official matches he scored 105 goals in 151 games, while the club's official site says he scored 181 in 237.

"Evaristo has more goals than me for Barcelona. However, I have more official goals as he scored many in friendly matches," Rivaldo, who scored 129 in 235 between 1997 and 2002, tells BBC Sport.

"He has a lot of recognition at Barcelona; there are pictures of him in the locker room. He was a great player who did a lot for Brazilian football and in Barcelona I realised that greatness because so many people talked about him."

Regardless of whether friendlies are included, to this day Evaristo retains the best goals-to-games ratio of any Brazilian to play more than 50 games for Barcelona. And one thing never disputed is his most notable contribution.

On 23 November 1960, in the second leg of a tight European Cup tie against Real Madrid and in front of 120,000 fans at the Nou Camp, Evaristo scored a stunning diving header with eight minutes to go. The goal, immortalised in a grainy black-and-white photo and still on prominent display inside the stadium 60 years on, eliminated Barcelona's most bitter rivals from that competition for the first time, ending their hopes of a sixth successive title.

"There was a great rivalry between the two cities because Madrid is the capital and Barcelona always fought for independence," says Evaristo.

"Madrid was seen by many as General Franco's team, so it also had this great political rivalry - although I never felt any political interference. That goal broke Madrid's hegemony. It felt like a title for Barcelona because of the rivalry and the fact it eliminated Madrid.

"It was crazy. We celebrated a lot after that match…"

Real Madrid less so. In the excellent book Fear and Loathing in La Liga, author Sid Lowe writes that, during the post-game banquet, Madrid's players tried to beat up the English referee and his assistants, who had disallowed four goals, with Barcelona's players intervening to defuse the situation.

Evaristo is diplomatic. "I don't remember that, no," he says. "Madrid complained a lot, but I never saw any threats of violence. The players had actually played quite calmly."

Barcelona went on to reach the final for the first time in the club's history, with Evaristo scoring six times in total, including two in the semis. At the Wankdorf Stadium in Bern, they lost 3-2 to Benfica in a match now remembered as the 'Square-Posts Final'.

"It was a very sad day for Barcelona because we had everything to be European champions," says Evaristo. "Everything except luck. The goalposts were square and we hit them four or five times. If they were round the ball would have gone in. But Benfica had a great team."

Within 12 months of that 1961 final, Evaristo had done the unthinkable and joined Real Madrid after a dispute with Barcelona regarding naturalisation. Yet in stark contrast to the infamous transfer of Luis Figo 38 years later, the club's fans directed their anger not at the player but at the board.

"Barcelona wanted me to become Spanish to open the possibility for them to bring in another foreign player and I didn't want that," he says.

"In Madrid that wasn't the case. That's why I moved there, otherwise I'd have stayed at Barcelona, which I liked more."

It was not the first time the actions of the Barcelona board in relation to Evaristo had been open to question. When he signed his contract in 1957, there was an agreement that, if selected to represent Brazil at the World Cup the following summer, Barcelona would not stand in his way.

Having played every minute of the two-legged World Cup qualifier against Peru and with a total of eight goals in 14 games, Evaristo expected to be a starter for his country. But with Spain having failed to qualify, the Spanish Cup went ahead at the same time as the tournament in Sweden, and Barcelona reneged on their promise to release him.

Brazil would go on to win their first World Cup, with a 17-year-old Pele scoring a hat-trick in the semi-final and two more in the final. Evaristo, who would face the youngster two years later when Santos toured Europe, never wore the famous yellow shirt again.

"I was very upset not to be there, but I followed the games on the radio," he says.

"On the day of the final, I was at a training camp because Barcelona had a game the next day and my dad called to break the news. I was very happy to hear Brazil won because it was my friends who were playing - and as I played the games that helped us qualify, I feel a bit like a champion too, you know?"

Ultimately, Evaristo's absence in 1958 and the fact his exploits in Barcelona went largely unreported at home left his standing in Brazil somewhat understated.

Brazilian journalist Milton Neves wrote of Evaristo: "If they had TV in the 1960s, he would be regarded like Ronaldo." Mario Zagallo, who won the World Cup twice as a player in 1958 and 1962 and again as manager in 1970, called him "the type of player who would have had a place in any team of his choice".

Rivaldo adds: "No doubt football has changed a lot. Today it's easier for a player to stand out with TV, internet and social media. For sure though, if Evaristo had been playing in another era, his reputation would be totally different from the one he ended up having in the 50s and 60s. He was a special player."

When Evaristo quit Barcelona, he had offers from Italy and France but elected to stay in Spain where, despite a serious knee injury limiting him to just 19 appearances and six goals for Madrid, he continued his habit of collecting domestic trophies by adding two league titles in two seasons.

Much like at Barcelona, Madrid's official site lists him as a "football legend", alongside fellow former club stars Alfredo di Stefano, Ferenc Puskas, and Raul.

Evaristo always intended to return to Flamengo and he did so in 1965, adding another league title before retiring a year later, aged 33.

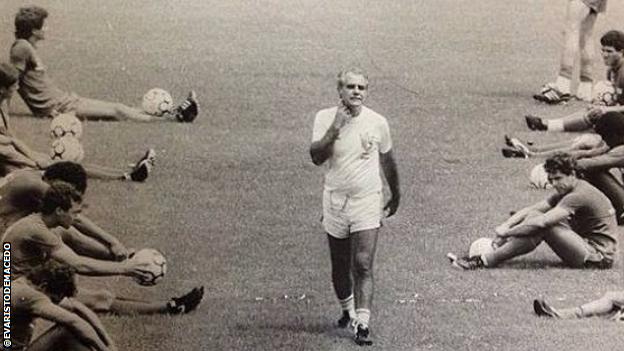

During a 36-year career in management that followed, he won various trophies in Brazil with clubs including Santa Cruz, Gremio and Bahia, gave Dani Alves his professional debut, and fought with Romario while in charge at Flamengo.

In April 1985, Evaristo was named Brazil manager and asked to prepare for the following year's World Cup in Mexico. But he was dismissed after only a month following three defeats from six and a stubborn refusal to select any overseas-based players. He would still make football's biggest showpiece though - in unlikely fashion.

"I wasn't going to allow the Brazilian Federation to interfere in my squad selection, so I left," Evaristo says.

"I already had a proposal to coach Qatar anyway, so I went there and then when Iraq needed a coach for the World Cup, I was asked to do it.

"I worked directly with Saddam Hussein's son, but I never went to the country. We met in Europe and then went straight to Mexico because Iraq was at war at the time."

Iraq, making their only World Cup appearance to date, lost all three group matches; their squad disrupted by various players being conscripted to serve in the country's conflict with Iran.

Since retiring in 2005, Evaristo passes most days watching Flamengo and spending time with family - he became a great-grandfather earlier this year.

Yet as he speaks by phone from his Ipanema apartment surrounded by trophies, photos and other assorted memorabilia, it is arguably Evaristo's three children that best represent his playing career: Evaristo Jr was born in Catalonia, Luis Augusto in Rio, and Maria Mercedes in Madrid.

"I'm very proud to have worked in football for 56 years and to have achieved such success," he says.

"Football, Flamengo, family and friends. That is my life now."

Africana55 Radio

Africana55 Radio