This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

By Marianna Brady

BBC News, Washington

The pandemic is the biggest global story in generations, but a year ago as borders were closing we did not know how it would unfold. We asked readers to share and talk about their first text messages about the virus.

Last March, the US watched as the virus spread around the world.

Within weeks of the first recorded case in the US, the World Health Organization had declared it a pandemic, borders were closed, and millions started losing their jobs.

Five people look back at the first time "coronavirus" appeared in their text messages - and what they wished they had known back then.

24 JANUARY: 'And suddenly, my senior year was obliterated'

As January rolled to a close, the country was wrapped up in its own political drama - the Democratic primaries. And Austin Wu, then a senior at the University of Iowa, was right in the thick of it.

In his free time, he was knocking on doors for Bernie Sanders and enjoying Friday beers at the local bar with friends. Like most Iowans around the time of the caucus - which determines who will run for president in each party - politicians were visiting campus daily to court students to back their politicians.

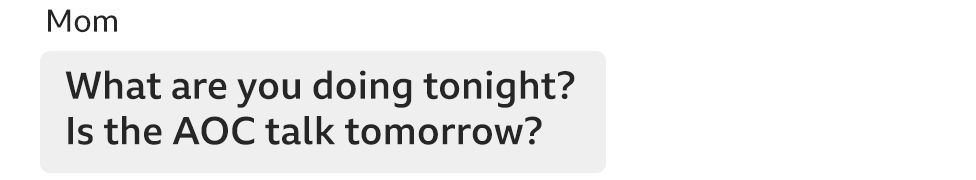

Just three days after the US announced its first case of the virus, Austin was going to see Democratic Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez campaign for Bernie Sanders.

"She spoke in a packed music hall full of 600 students," he said, admitting that it seems strange looking back on the event now knowing the virus was already in the country.

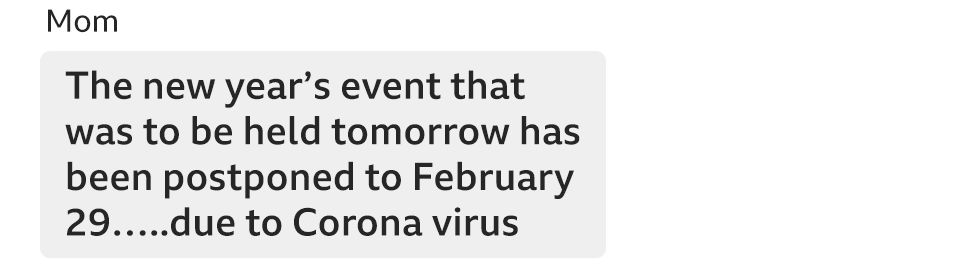

In that same text exchange, his mom told him the Chinese New Year event was postponed due to the coronavirus - which she spelled as two words.

Austin, whose Dad is Chinese and Mom is Korean, grew up in Iowa and sometimes attended Asian cultural events with his parents.

Many international students on his campus went home for the winter holiday and had just come back from China, and tales of the virus had reached his campus.

"The people who were directly connected to China were ahead of the curve by a solid month-and-a-half," he said, regarding the decision to postpone the Chinese New Year event.

A week later, on 31 January, Trump declared a ban on travellers coming in and out of China.

In the early days of the pandemic, he remembers lashing out at people on Twitter - including conservative activist Charlie Kirk - who referred to the virus as the Wuhan flu.

But Austin said he was still clueless about how world-altering the pandemic would end up being.

"I don't think I grasped the true scale of the virus until the first universities on the East Coast started closing in early March and my senior year was obliterated. I had to move back in with my parents."

29 FEBRUARY: 'We were trying to get her out of there'

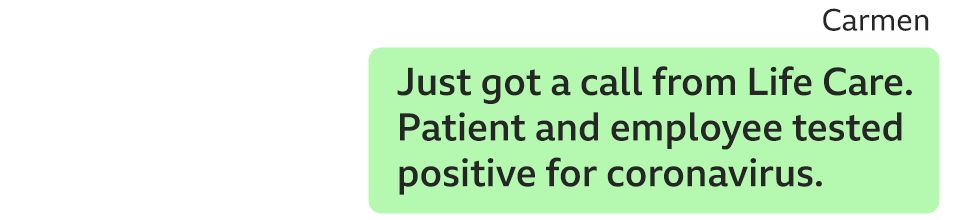

The first death from coronavirus was recorded in the US on 29 February, the same day Carmen Gray got a call from her mother's nursing home.

Two cases of the virus had been recorded at LifeCare nursing home near Seattle, Washington - the facility where her mother lived.

"I went there every day. But on February 29th, I got a phone call from them telling me I couldn't come to visit because a resident and employee test positive for coronavirus."

She texted her sister, Bridget, with the news.

A few days later her mother also tested positive.

"We were terribly frightened. We continued to visit daily outside the window."

Carmen, who had been exposed to the virus, desperately called health departments and hospitals to find out what to do - but no one had an answer. At the time there were only 70 recorded cases of coronavirus in the country.

"We couldn't get any help - there was no public testing at that point. I couldn't get anyone to tell me what to do or where to go."

Her mother got sicker, but eventually recovered, only to be diagnosed a second time later that year.

"She started talking to dead people and still has brain fog," said Carmen, who eventually took her mother out of the nursing home and into a new facility.

6 MARCH: 'Little did I know my Mom would die 24 days later'

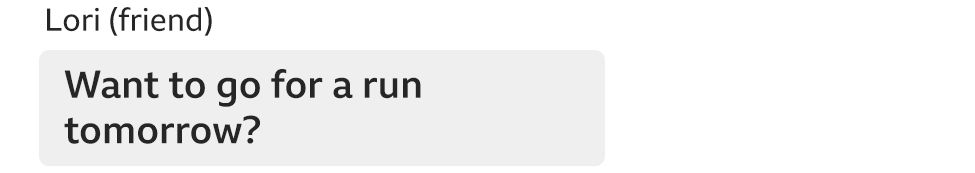

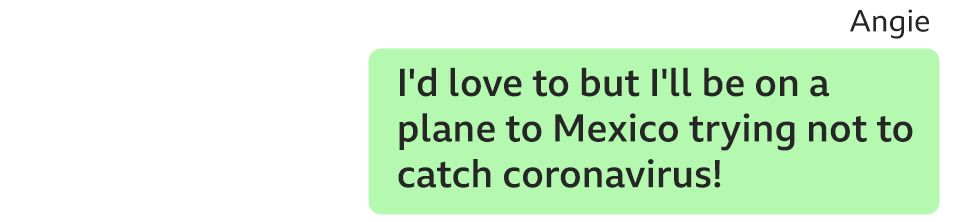

Angie Kociolek was getting ready to leave the country for the first time in seven years when her friend texted her about going on a run. She jokingly quipped that she was on her way to Mexico and hoped not to catch the virus.

An avid outdoors-lover who lives in Montana, the 50-year-old spent the week kayaking in Mexico with a tour group before flying back to the US on 15 March.

Coronavirus dominated many conversations on her trip, but Angie said she was more relaxed than most of the other travellers.

When she came home, she was on a high from her great trip.

Two days later, her sisters called to tell her someone had tested positive for coronavirus in their mother's nursing home in New Jersey.

"It turns out it was my mom's roommate. A few days later, my mom tested positive," said Angie.

Her mother, at age 93, was alone. And then things took a turn for the worse.

When the first cases of the virus appeared at the nursing home, the state decided to evacuate 78 elderly residents to a facility 45 minutes away.

Angie's mother, Annette, was strapped to a gurney by people in Hazmat suits and carted away.

One bystander told US media that "people were loaded up like cattle."

"It was horrible. When I close my eyes, even today, I still see it."

Angie's sisters, who lived twenty minutes away, were just as helpless as she was on the other side of the country.

"We were never given the option to keep my mother where she was," Angie said.

"We made desperate attempts to find out the treatment plan, but there was none."

"And within five days of being moved, on my sister's birthday, she passed away," Angie said.

"When I sent that text on 6 March", Angie reflected, "little did I know my mother would contract Covid-19 and die just 24 days later."

10 MARCH: 'In this moment I knew things were getting real'

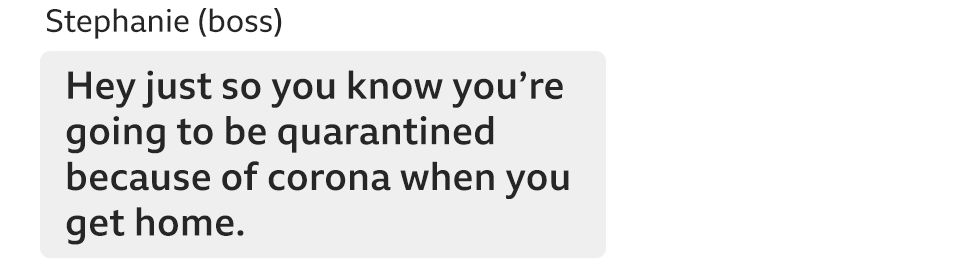

Every year, Tatiana McArthur goes to England in March to visit her husband's family, and it was the same in 2020.

Despite several European countries already in lockdown, the 33-year-old travelled to the United Kingdom.

Everything was normal at first, she said. The UK didn't go into lockdown until 23 March, at which point she was already back in the US.

But her colleagues back at home in Wisconsin were starting to panic as the virus was labelled a pandemic - on 11 March - by the World Health Organization.

"I came back from dinner one night and had several messages and emails from my manager back home," which turned out to be the first mention of the virus in her texts.

"She was telling me I would not be allowed in the office when I got back and would need to quarantine."

On 12 March, President Trump halted travel from Europe.

Although the ban did not include the UK at first, Tatiana and her husband were caught up in the historic hours-long lines in Chicago's O'Hare airport. People were stunned by images shared on social media of the airport full of panicked travellers trying to make it back inside the country after the closure was enacted.

"It was one of those Disney World lines where they don't show you the whole thing but it winds around corners," she said.

There were signs warning travellers to stay socially distanced, but they were crammed "shoulder to shoulder" due to the unexpected influx of travellers.

"We could hear people coughing. People were standing in line for over five hours just to get through customs," she said.

"I naively thought it would be better managed than it was, but in this moment I knew things were getting real."

23 MARCH: 'We were making decisions in the blind'

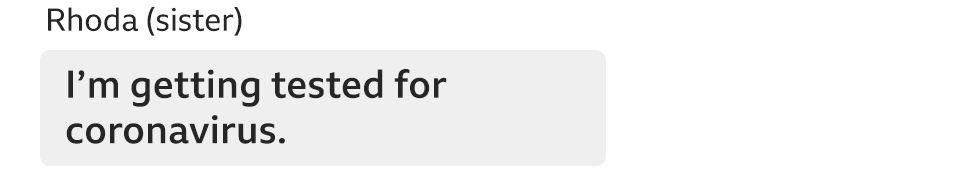

Reverend Marshall Hatch says his first conversation about coronavirus wasn't in the form of a text, because he and his 73-year-old sister Rhoda didn't text often. But he remembers the phone call like it was yesterday.

It was one of the last times he spoke to Rhoda.

After attending a friend's funeral with out of town guests, Rhoda's asthma began acting up on 16 March.

Her doctor scheduled her to get a coronavirus test.

She then called her brother to tell him she would get one the following week - which is the call Marshall remembers so vividly.

But Rhoda's asthma worsened overnight and on 25 March, Marshall drove her to the emergency room.

Rhoda had dealt with asthma flare ups her entire life, but this one felt different.

"Rhoda said it didn't feel like a normal asthma attack - it felt different and she was more tired," said Marshall.

A few days later, the doctor called Marshall and asked for his permission to intubate Rhoda.

"Over that week, we were making decisions in the blind," said Marshall.

He thinks he would have made better decisions about her care if he had known more about the virus, and thinks the doctors would have too.

He begged the hospital to let him visit her one last time.

They finally agreed since she was still technically an asthma patient, and not in the Covid ward. She eventually did test positive for Covid, and died on 4 April.

Africana55 Radio

Africana55 Radio