This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Since Brexit, the rules on passport validity for British visitors to the European Union have tightened. But the UK government tells travellers the regulations are worse than they actually are.

After requests from The Independent, the Home Office has taken down its defective post-Brexit passport checker.

But the government continues to publish inaccurate information about the validity of British travel documents in the European Union.

Some airlines continue to deny boarding to UK passport holders who have documents that are valid for travel, laying themselves open to compensation claims.

These are the key questions and answers based on EU rules, not the UK government’s misinterpretation of them.

What’s changed?

While the UK was in the European Union, British passports were valid up to and including their expiry date for travel within the EU. But since the end of the Brexit transition phase, British passport holders are treated as “third country nationals” with stipulations about passport issue and expiry dates – together with limits on the length of stay almost everywhere in Europe.

For the avoidance of doubt, these are not “new EU rules” – they were decided while the UK was in the European Union.

What is required for my passport to be valid?

The requirements for the Schengen Area – comprising most EU countries plus Switzerland, Norway, Iceland and a handful of micro-states – are crisply expressed on the Travel page of the European Union’s Your Europe site: “If you are a non-EU national wishing to visit or travel within the EU, you will need a passport

- valid for at least three months after the date you intend to leave the EU country you are visiting,

- which was issued within the previous 10 years.”

Why the line about ‘issued within the previous 10 years’?

For many years, until September 2018, the UK had a generous policy of allowing credit for “unspent” time when renewing a passport, issuing documents valid for up to 10 years and nine months.

So a passport issued on 31 October 2012 could show an expiry date of 31 July 2023.

This was fine around Europe and the world for decade – until Brexit, whereupon a longstanding rule kicked in. For non-members of the EU hoping to enter the Schengen Area, a passport must have been issued in the past 10 years.

With a passport issued on 31 October 2012, regardless of the expiry date, you will not be allowed to enter the EU from 1 November 2022.

Until September 2018 the government appeared unaware of the problem. Once the issue was identified, the practice of giving up to nine months’ grace ended abruptly.

But the “issued less than 10 years ago” and “valid for three months” rules are not combined?

Correct. There is no need to have a passport issued less than nine years, nine months ago. The two conditions are independent of each other.

The Migration and Home Affairs Department of the European Commission in Brussels told me: “Entry should be allowed to those travelling with passports issued within the previous 10 years at the moment of entry into the Schengen area.

“The condition that the passport must have been issued within the previous 10 years does not extend for the duration of the intended stay. It is enough if this condition is fulfilled at the moment of entry.

“To give a practical example, a non-EU traveller arriving on 1 December 2021 for a 20-days stay in the EU with a passport issued on 2 December 2011 and valid until 2 April 2022 will be allowed entry.”

But the UK government claims otherwise, saying: “For some Schengen countries your passport may need to be less than 10 years old during your whole visit, and the three months at the end of your visit may need to be within 10 years of your passport’s issue date.”

In other words, the government says, your passport must have been issued no more than nine years and nine months ago.

This is nonsense, as I have pointed out to officials – including supplying explicit confirmation from the European Commission in Brussels.

Unfortunately, some travel firms and airlines seem to persist in applying the incorrect information.

What does the UK government say?

A government spokesperson said: “The European Commission has explicitly advised us, including in correspondence received [on 10 November 2021], that the conditions of a passport being less than 10 years old and valid for three months post-return date are cumulative.

“We are engaging with the Commission to seek further clarification and, if this is no longer the case, will update our advice in due course.”

In establishing a British traveller’s right to visit the EU, the UK’s interpretation of European rules is irrelevant. The Independent has contacted the leading airlines with the correct information as provided by the European Commission.

Which is legally superior: European rules or the UK’s unusual interpretation?

Europe’s: the destination’s attitude is what counts. During the summer Jet2, not unreasonably, followed UK advice and barred a number of passengers from flights to Europe. After The Independent pointed out that this was in breach of European air passengers’ rights rules, Jet2 apologised and compensated the affected holidaymakers.

Britain’s biggest holiday company, Tui, has changed its policy to align it with European rules. A spokesperson for the travel giant said: “Following new information provided, we can confirm that we have now changed our policy accordingly.

“Customers will not be denied boarding on the basis that their passport needs to meet both conditions dependently.”

If I get wrongly turned away, what are my rights?

For flights: you can claim denied boarding compensation (either £220 or £350, depending on the length of the flight) and associated costs – for example, booking another flight on a rival airline, or for wasted car rental and hotel expenses that cannot be reclaimed.

I’ve just read a report saying I need six months remaining for Europe?

Some news outlets, regrettably, continue to publish incorrect information. Ignore it.

Does that 10-year-plus rule apply anywhere else in the world?

No as far as I am aware. The concern around the date of issue is relevant only for travel to the European Union – not for the rest of the world.

For destinations outside EU, the only significant consideration is the expiry date. And for destinations such as Australia, the US and Canada, your passport is valid up to and including this date.

So with that passport expiring on 31 July 2023, you could be in New York until that very day (though you would need to get a daytime flight back to avoid your passport running out en route.

What about children?

Passports for under-16s are typically valid for five years (plus any extra credit). A child’s passport issued for five years and nine months is clearly within the 10-year limit, and there is no possibility of breaching that condition.

(During 2021, the Home Office’s defective passport checker stripped all extra credit, which was both wrong and unhelpful. The online checker has now been switched off.)

But beware of the three-months-remaining-on-exit rule, which children are more likely to fall foul of because of the shorter duration of their passports.

When are you going to renew your passport?

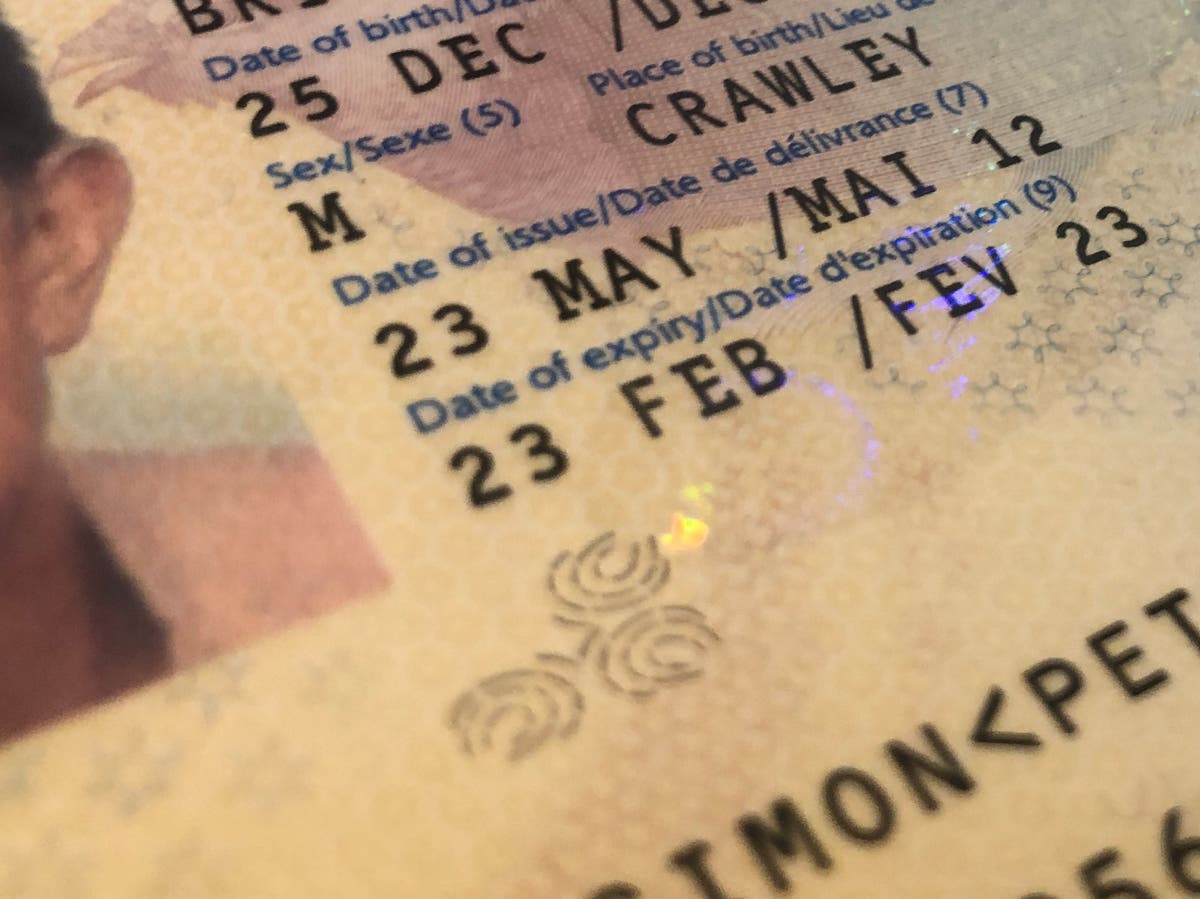

It was issued on 23 May 2012 and expires on 23 February 2023. The passport is therefore valid for departure to the EU up to 22 May 2022 for a stay of up to 90 days (minus time I have spent in the EU in the previous 90 days).

I will renew it in advance of the next planned trip to Europe after that date.

What about this 90/180 day rule?

For trips to the Schengen area (most EU nations plus Switzerland, Norway, Iceland and some small countries) British passport holders can stay a maximum of 90 days in any 180. That’s roughly three months in six.

it is tricky to explain, but I shall do my best. Imagine a calendar that stretches back almost six months from today. What happened more than 180 days ago is irrelevant. What counts is the number of days you were either inside (I) or outside (O) the Schengen Area in the past 180 days.

You can easily keep count on a calendar yourself, either printed or digital.

If “I” hits 90, you must leave that day and stay out for almost three months, to accumulate 90 “Os” in a row. Then you can go back in, for a maximum of 90 days.

During the course of a calendar year, it could work like this (assuming no travel to the EU in the previous six months).

- 1 January: enter the EU and stay for 90 days until the last day of March, when you must leave.

- 1 April: remain outside for 90 days, which takes you to 29 June.

- 30 June: enter the EU and stay for 90 days, until 27 September. Then leave.

- 28 September: remain outside the EU until 26 December.

For longer stays, some countries offer visas that allow British citizens to remain for months on end. If you get one of these, then the time spent in that country does not count towards the “90/180” rule – in other words, you can explore other EU countries with a fresh calendar.

What about non-Schengen EU members?

For British visitors to Ireland, there are no limits on passport validity. Indeed, a passport is not legally mandatory for British travellers to the republic, though some airlines insist on it.

Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus and Romania have identical rules to the Schengen Area: passport issued in the past 10 years, and with three months validity remaining on the day of leaving the country. But time spent in any of these nations does not contribute to the “90/180” day total.

Help! My passport is full of stamps and I have no space left. Will I be turned away?

No, even though Eurostar warns British passport holders : “Check that you have a clear page in your passport as it will need to be stamped with your travel date when you’re travelling to and from the EU.”

The EU’s Practical Handbook for Border Guards is explicit about a “document enabling a third-country national to cross the border [that] is no longer suitable for affixing a stamp, as there are no longer available pages”.

It says: “In such a case, the third-country national should be recommended to apply for a new passport, so that stamps can continue to be affixed there in the future.

“However, as an exception – and particularly in the case of regular cross-border commuters – a separate sheet can be used, to which further stamps can be affixed. The sheet must be given to the third-country national.

“In any case, the lack of empty pages in a passport is not, in itself, a valid and sufficient ground to refuse the entry of a person.”

Africana55 Radio

Africana55 Radio