This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Thousands of women in England with mental health problems are being given electric shock treatment despite concerns the therapy can cause irreparable brain damage.

NHS data seen by The Independent reveals the scale of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) prescribed disproportionately to women, who make up two-thirds of patients receiving the treatment.

Health professionals have warned the therapy can cause brain damage so severe recipients are unable to recognise family and friends or do basic maths.

While some patients say the therapy profoundly helped them, leading mental charities have branded it “damaging” and “outdated” and called for its use to be halted pending an urgent review or banned entirely.

Statistics obtained through Freedom of Information requests by Dr John Read, a professor at the University of East London and leading expert on ECT, showed 67 per cent of 1,964 patients who received the treatment in 2019 were female.

ECT was given to women twice as often as men across 20 NHS trusts in the UK, his research found. The trusts also said some 36 per cent of their patients in 2019 underwent ECT without providing consent.

The NHS could only provide statistics on whether ECT was successful in 16 per cent of trusts, while just 3 per cent of trusts had mechanisms in place to monitor side effects. The audit of ECT clinics by Dr Read and his colleagues found around 2,500 patients undergo ECT in England every year, with people over the age of 60 making up 58 per cent.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Nice), which provides recommendations that guide NHS treatment decisions, said its guidelines stipulated doctors “should only consider ECT for acute treatment of severe depression that is life-threatening and when a rapid response is required, or when other treatments have failed”.

A spokesperson added patients should be fully informed of the risks associated with ECT and the decision to deploy the treatment “should be made jointly with the person with depression as far as possible”.

The Royal College of Psychiatrists said ECT “can have side effects” but noted that “most people who have ECT see an improvement in their symptoms”.

However, Dr Read claimed the Nice guidelines are routinely ignored. His study found many NHS trusts admitted to giving patients ECT without first offering them treatments such as counselling or cognitive behavioural therapy.

I couldn’t remember the names of people. I would get through a sentence and forget the word for a house. I’d lost vocab. I couldn’t remember my kids’ birthdays. You lose all your memories from years ago

Sue Cunliffe

The academic, who worked as a clinical psychologist for almost 20 years, also argued guidelines are “very weak” as they fail to spell out specific risks patients should be told about.

“They also don’t spell out the fact ECT is barely better than placebo,” he added. “We have bombarded Nice with research showing that ECT is unsafe in terms of causing brain damage and memory loss. They have just ignored our correspondence.”

In every country where research has been conducted, ECT is used twice as much on women as men, Dr Read said. He noted most psychiatrists in the UK will not use ECT on patients but suggested they would speak out against their colleagues who do so.

Dr Read said the most recent efficacy study was conducted in 1985 and argued previous research showed very little evidence of its positive impacts.

“A major adverse effect is memory loss. Studies find between 12 and 55 per cent of people get long-lasting or permanent brain damage which results in memory loss,” he added.

“We also know women and older people who are the target groups are paradoxically more likely to suffer memory loss than other people. They should be the groups who are getting it less because of the dangers.”

Sue Cunliffe, who began ECT in 2004, told The Independent it “completely destroyed” her life despite a psychiatrist telling her there would be no long-term side effects.

The former children’s doctor, 55, was referred to a psychiatrist after suffering from depression following issues with her ex-husband, to whom she was married to for two decades.

Dr Cunliffe underwent two courses of ECT, involving 21 sessions, each under general anaesthetic in hospital. She said she suffered “dreadful” memory loss throughout the treatment.

Sue Cunliffe

(Sue Cunliffe)

“By the end of it, I couldn’t recognise relatives or friends,” she said. “I couldn’t count money out. I couldn’t do my two times table. I couldn’t navigate anywhere. I couldn’t remember what I’d done from one minute to another.

“I couldn’t remember the names of people. I would get through a sentence and forget the word for a house. I’d lost vocab. I couldn’t remember my kids’ birthdays. You lose all your memories from years ago.”

Peter McCabe, chief executive of Headway, the brain injury association, said he was “concerned with reports from patients experiencing neurological difficulties after ECT” and called for further research and an urgent review.

He added: “We are aware of the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ assertion that ‘rigorous scientific research has not found any evidence of physical brain damage to patients who have had ECT’. However, it also accepts further research into the long-term effects of this treatment is needed.”

Stephen Buckley, mental health spokesman at Mind, told The Independent the charity backed calls for a “comprehensive review into the use of ECT,” which he described as a “potentially risky physical treatment”.

Alexa Knight, associate director of policy and practice at the charity Rethink Mental Illness, stressed consent for ECT must be sought from patients and noted this was currently not required if the individual is treated in an emergency under the Mental Health Act.

Indy Cross, chief executive of Agenda, a charity which campaigns for women and girls at risk, called for ECT to “be banned immediately”.

During her second course of the treatment, Dr Cunliffe said her side effects worsened as the doses of electric shocks increased – rising from around 460 to 700 milicombes. The maximum dose in Europe and America is 500 milicombes but in Britain dosage can be increased to a maximum of 1000 milicombes.

She said: “What is important and what is never discussed is the fact your brain doesn’t like to fit. Every time you go in, you need a different dose of electricity to fit.

“They are still unclear as to how to dose safely and actually when they give you larger doses, they do not tell you the treatment is getting riskier in terms of brain damage.”

In my view, there is never a good reason to give an animal or human electric shocks to the brain. In another circumstance, it is fatal - you’re not meant to get electrocuted.

Dr Jessica Taylor

Dr Cunliffe said health professionals initially dismissed her symptoms being the consequences of ECT. However, in 2007, an NHS neuropsychologist diagnosed her with reduced brain functioning from ECT, she said.

By then, Dr Cunliffe was unable to use computers and struggled to read, problems which persisted for years after her ECT and stopped her being able to work.

“I forgot huge swathes of my medical knowledge,” she added. “It was very distressing. It is 17 years since I finished the treatment and I’ve made a lot of improvements. But I get excessively tired and I have been left with the long-term effects of brain damage.”

Dr Cuncliffe said she used to sometimes work more than 100 hours a week but now struggles during three-hour volunteer shifts in a community cafe.

She said: “I have a got a lot of my intelligence back but what happens is that your brain tires so much. It limits my independence, I wouldn’t dare drive a long journey – I feel too exhausted. Because I get really tired, I have help at home.

“I know I’m not the only one who has lost their job after having ECT. I know another doctor who lost their job, a man who lost his job as a manager in a care home, and someone in banking who lost their job”.

Dr Cunliffe, campaigning for an inquiry into how ECT is used in the UK, argued psychiatrists “downplay” side effects and fail to properly warn patients.

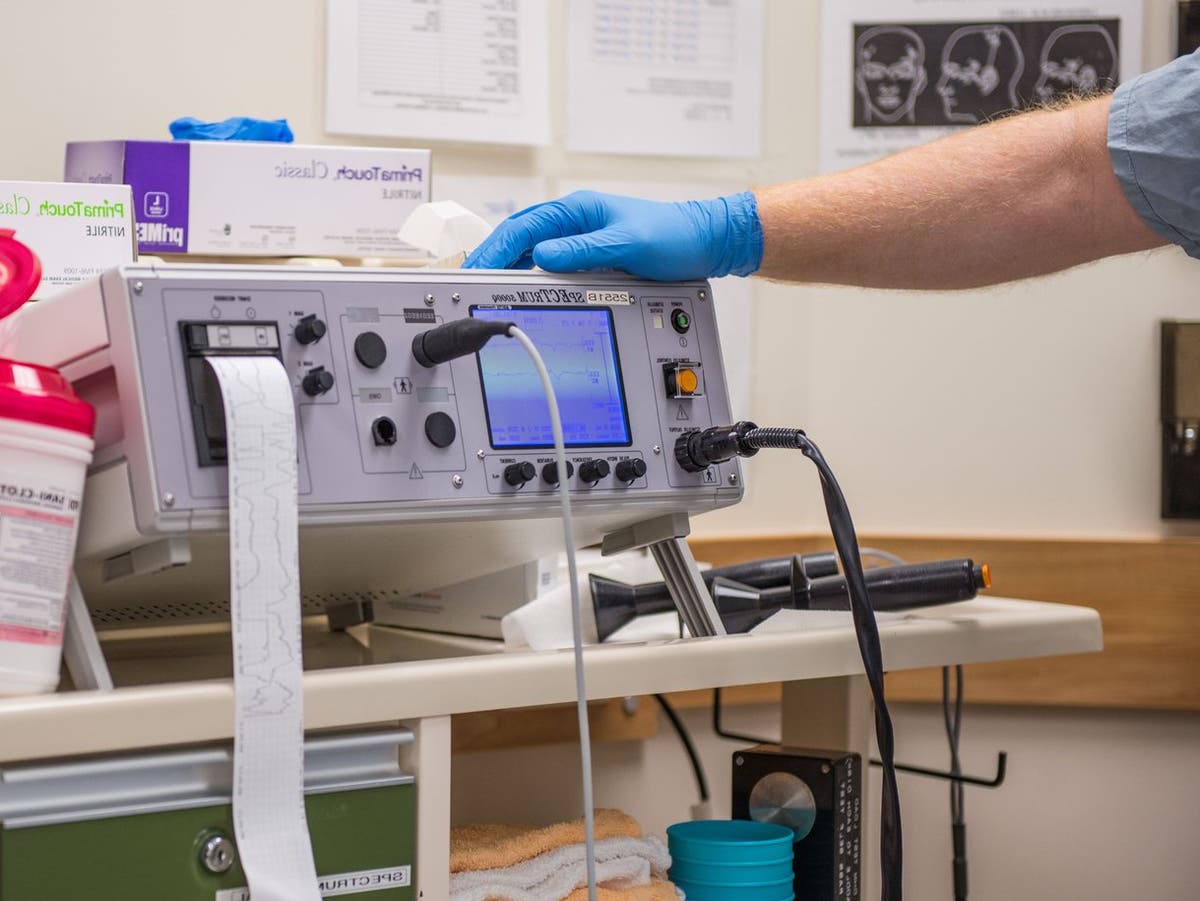

She noted manufacturers have a list of warnings that ECT can cause brain damage written on the machine’s manual and expressly urges all health professionals to inform patients of side effects. But health professionals are not properly seeking consent for ECT from patients or adequately keeping tabs on them while they are going through treatment, she claimed.

Dr Cunliffe added: “I used to have an Apple Mac brain which could process huge amounts of information. Now it is an old computer which closes down.”

Jessica Taylor, a prominent psychologist who explores ECT in her new book Sexy But Psycho, called for the “dangerous and barbaric practice” of ECT to immediately be banned in the UK.

Dr Taylor, who specialises in the pathologisation of women in mental health settings, said she had met dozens of people who have undergone ECT, including a handful of women who say they have suffered brain damage as a result.

She encountered ECT when previously working in frontline services helping teenage girls and women who had been raped, she said.

“They were given several rounds of ECT because services and professionals around them thought they were resistant to treatment,” Dr Taylor, who set up Victim Focus, an organisation which tackles discrimination against abuse victims, added.

The psychologist gave the example of a 15-year-old girl who was referred for ECT less than a year after being raped.

Dr Taylor said: “I was gobsmacked anyone in the world was having ECT let alone a teenage girl in the UK. Generally, when we talk about ECT, the public assumes it is banned. When people think about ECT they think about horror movies like Shutter Island.

“In my view, there is never a good reason to give an animal or human electric shocks to the brain. In another circumstance, it is fatal – you’re not meant to get electrocuted.”

She argued health professionals fail to properly explain the damage which ECT can cause and claimed psychiatrists sometimes “have a god complex”.

“They are on a power trip,” Dr Taylor added. “They often say things which imply ‘mental health is the same as physical health and it needs to be treated like a disease’. They have a really medicalised understanding of humans and trauma – they see it as an illness, and they see ECT as the cure.”

She pointed to misogyny as the reason why women are disproportionately given ECT and women over 60 are more likely to be given the treatment.

“That is a group of women we often ignore in society,” Dr Taylor said. “It made me wonder is this part of menopausal women being seen as crazy. Then there is the whole stereotype of she is an older woman, she is invisible, she won’t shut up, she is a problem to our services. And there is nothing anyone can do for her. So give her ECT.”

Africana55 Radio

Africana55 Radio