This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

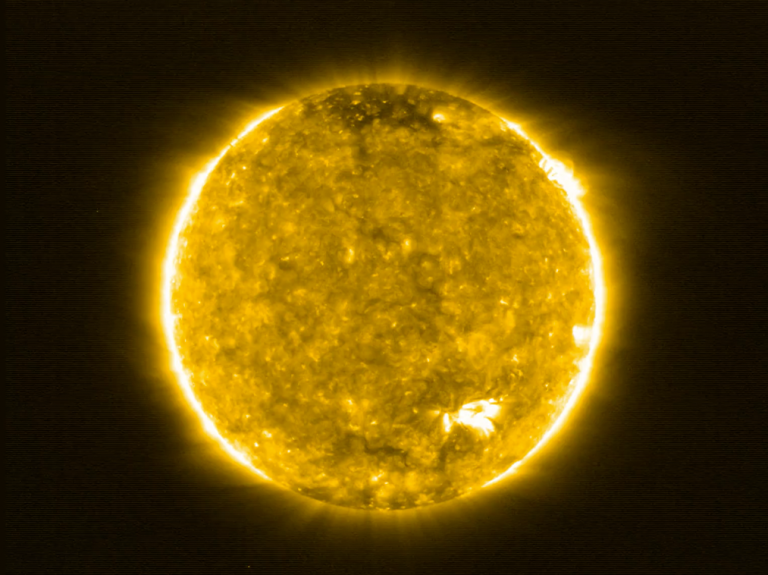

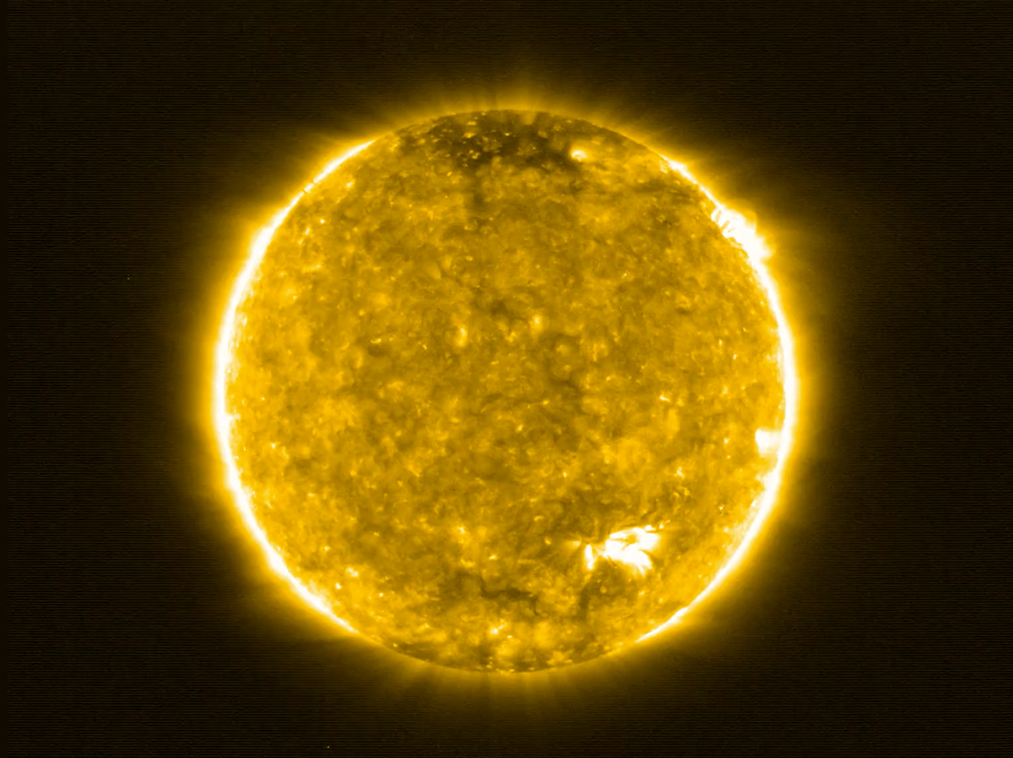

The Solar Orbiter spacecraft, a joint European Space Agency (ESA) and Nasa mission, has sent back never-before-seen images of the Sun’s surface.

The satellite took photographs of tiny solar flares near the surface of the star dubbed “campfires”.

Its sensors gazed at light that is 13 times brighter than looking directly at the Sun here on Earth, for 10 days at a time.

The vehicle was only 77 million km away from the Sun, about half the distance between Earth and the star.

The images were captured by the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) on the Solar Orbiter, taken when the craft was in its first perihelion – the point in its elliptical orbit closest to the Sun – between the orbits of Venus and Mercury.

Created with Sketch.

Created with Sketch.

1/12

Credit: ESA, Nasa

2/12

Credit: ESA, Nasa

3/12

Credit: ESA, Nasa

4/12

Credit: ESA, Nasa

5/12

Credit: ESA, Nasa

6/12

Credit: ESA, Nasa

7/12

Credit: ESA, Nasa

8/12

Credit: ESA, Nasa

9/12

Credit: ESA, Nasa

10/12

Credit: ESA, Nasa

11/12

Credit: ESA, Nasa

12/12

Credit: ESA, Nasa

1/12

Credit: ESA, Nasa

2/12

Credit: ESA, Nasa

3/12

Credit: ESA, Nasa

4/12

Credit: ESA, Nasa

5/12

Credit: ESA, Nasa

6/12

Credit: ESA, Nasa

7/12

Credit: ESA, Nasa

8/12

Credit: ESA, Nasa

9/12

Credit: ESA, Nasa

10/12

Credit: ESA, Nasa

11/12

Credit: ESA, Nasa

12/12

Credit: ESA, Nasa

No other spacecraft has been able to take such images so close to the Sun.

“The campfires are little relatives of the solar flares that we can observe from Earth, million or billion times smaller,” said David Berghmans of the Royal Observatory of Belgium (ROB), Principal Investigator of the EUI instrument.

However, scientists do not know yet whether the campfires are ‘nanoflares’, smaller versions of larger flares, or caused by some other mechanism of the nuclear fusion reactions that happen within the Sun.

Nanoflares are tiny sparks used to heat the Sun’s corona, its outermost layer. This can reach temperatures of more than a million degrees Celsius.

This is 300 times greater than the surface of the star, which is a comparatively chilly 5500 degrees Celsius.

Despite decades of study, the mechanisms that heat this outermost layer are still not fully understood, but such discoveries are vital in the study of solar physics.

It’s possible these nanoflares could be the key to unlocking this mystery.

“It’s obviously way too early to tell but we hope that by connecting these observations with measurements from our other instruments that ‘feel’ the solar wind as it passes the spacecraft, we will eventually be able to answer some of these mysteries,” Yannis Zouganelis, Solar Orbiter Deputy Project Scientist at ESA, said in a statement.

“We are all really excited about these first images – but this is just the beginning,” adds Daniel Müller, ESA’s Solar Orbiter Project Scientist.

“Solar Orbiter has started a grand tour of the inner Solar System, and will get much closer to the Sun within less than two years. Ultimately, it will get as close as 42 million km, which is almost a quarter of the distance from Sun to Earth.”

The temperatures of these campfires will be tracked using a tool called the Spectral Imaging of the Coronal Environment (SPICE), which takes images using ultraviolet light.

“Spectroscopy is a powerful tool for the diagnostic of fundamental processes in hot plasmas. Each spectral line gives us a piece of the puzzle – combining information from all lines reveals the amazing complexity of the atmosphere,” said Dr Andrzej Fludra, the SPICE Instrument Consortium lead.

The Solar Orbiter has ten sensors: six which monitor the Sun and its surroundings, and four to monitor the environment around the ship itself.

This includes the Orbiter’s Solar Wind Analyzer (SWA), which measures heavy charged atoms of carbon, oxygen, silicon, and iron in the solar winds from the Sun’s inner heliosphere.

By comparing the data between the sensors, scientists will also be able to better understand how solar winds are generated. Solar winds are charged particles sent from the Sun which can affect the entire solar system.

“Already our data are revealing shockwaves, coronal mass ejections, phenomena called ‘switchbacks’ and fine-scale waves in the magnetic field that we are only able to see thanks to the extreme sensitivity of our instrument” said Professor Tim Horbury from Imperial College London.

On occasion, the Sun pushes out a great number of particles into space. These are called “coronal mass ejections” and, when they hit the Earth’s magnetic field, they can cause a huge surge of electrical current.

On Earth, these events can disrupt and damage satellites, affecting people’s mobile phones, GPS signals, and electricity networks.

The largest one to hit the Earth happened in 1859 and caused telegraph wires to alight. If the same event happened today, it could potentially cause continent-wide blackouts and severely damage the electrical grid.

Such damage could take months or years to repair, at a cost of up to £300 billion to the UK economy.

The Solar Orbiter itself was part of a combined effort from Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom, as well as Nasa from the United States.

It was built by Airbus Defence and Space in the UK, and launched from Nasa’s Cape Canaveral site in Florida on 10 February.

The Solar Orbiter will eventually get closer to the Sun than the planet Mercury, the closest planet in the solar system to the Sun

Gravitational forces from Venus and Earth will be used to direct the craft. By November 2021, it is expected to be in operational orbit.

Africana55 Radio

Africana55 Radio