This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Your support helps us to tell the story

Our mission is to deliver unbiased, fact-based reporting that holds power to account and exposes the truth.

Whether $5 or $50, every contribution counts.

Support us to deliver journalism without an agenda.

Louise Thomas

Editor

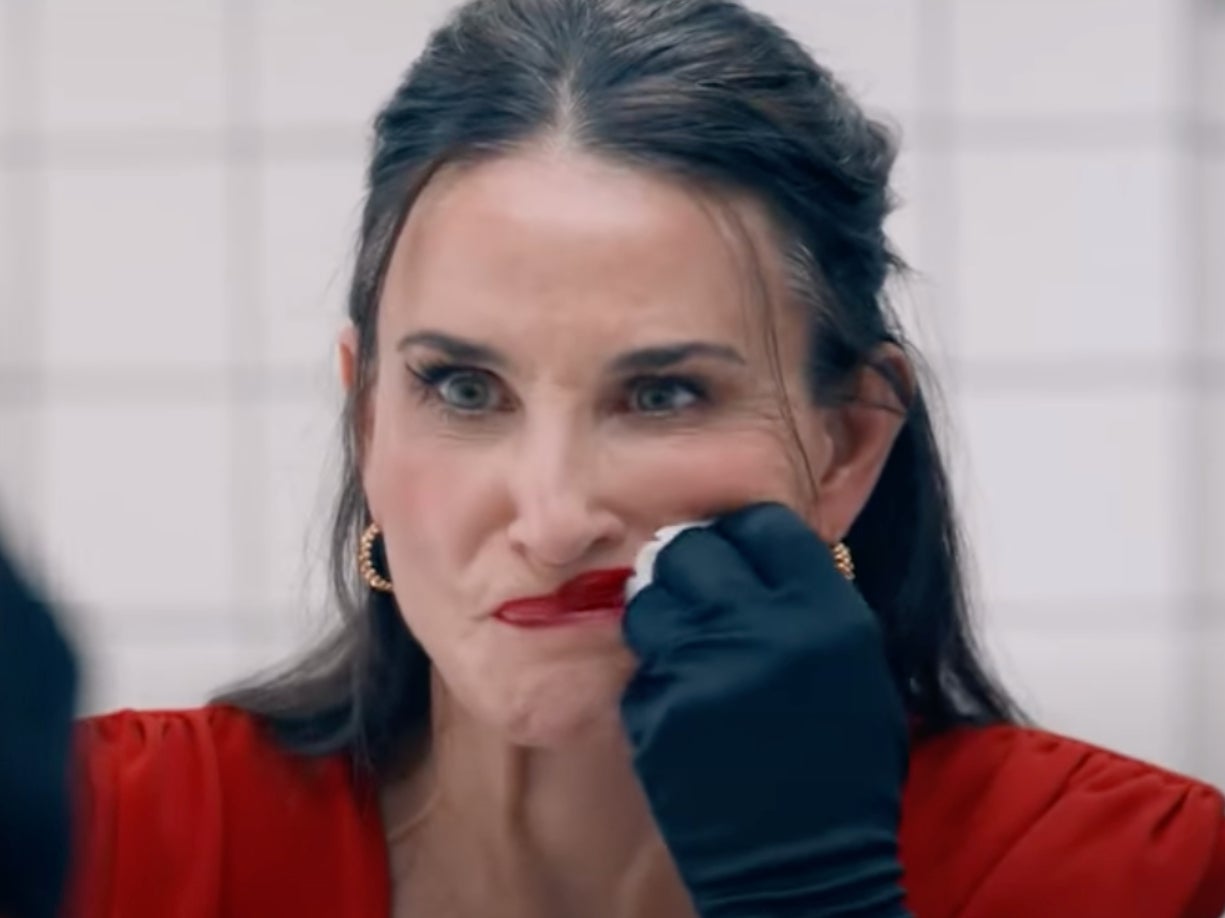

There’s a scene in The Substance – a viral sensation of a film I am far too squeamish to ever actually watch, but have read about obsessively since its release – in which lead character Elisabeth, played by Demi Moore, literally cannot leave the house for a date. She keeps returning to the mirror, over and over, tweaking, adjusting, putting on more and more make-up, looking at herself with increasing levels of criticism and self-disgust until she can look no more.

The extreme body-horror film, in which ageing star Elisabeth makes a Faustian deal to unlock a new, young, shiny version of herself after she gets axed from her own fitness show for being too old, has attracted global attention due to its sheer, unwatchable grossness. (Spoiler alert: the “new” version, played by a dewy Margaret Qualley, wrenches through a cavity in Elisabeth’s back and has to inject herself with the latter’s spinal fluid to remain suitably perky.) But the more subtle reason it’s sparked so much interest is the central theme of women’s body image, and the way in which being subject to public scrutiny and judgment – and inevitably found wanting – can completely warp our perspective and self-worth. At 61, Moore remains an objectively beautiful woman. But the character of Elisabeth views herself as a litany of endless physical imperfections and flaws; the monster she sees in the mirror is clearly a world away from what the audience is witnessing.

While you might shrug it off as fantasy, the issues explored amid the brutal gore are far from being make-believe. In a recent interview, comedian and Rivals actor Emily Atack opened up about the hugely damaging impact of intense media attention when she was younger, and her comments were a chilling echo of the scene in the film.

“The word I always land on is ‘confused’,” she told The Guardian of that period in her life in the late Noughties. She described how headlines either claimed she was “flaunting” her “ample assets” or centred on faux-distress as “Pals fear for Emily as she gains weight”, alongside deliberately unflattering photos. Meanwhile, she was splashed across the cover of FHM and branded the sexiest woman in Britain.

“I just didn’t get it,” she said. “I didn’t know if I was really beautiful or really ugly. The thing I was seeing in the mirror started to disintegrate and change. I’d obviously been seeing something different to everybody else.”

Though happily Atack has bounced back since her post-Inbetweeners struggles, her weight continues to be an issue to this day. Despite being a “tiny” size eight in her twenties, she was surrounded by articles describing her as “overweight”; stories praising the fact that she was representing “curvier” girls on screen; online trolls saying that she needed to lay off the bacon sandwiches.

This was compounded further when, keen to break into Hollywood, she had a meeting with a woman from LA who stated Atack wouldn’t even be considered for roles unless she starved herself down to a UK size 6: “I was so thin, and I was so hungry, and it wasn’t good enough.”

On the flipside, playing the role of Charlotte “Big Jugs” Hinchcliffe in The Inbetweeners had propelled her into “sex symbol” territory. To promote the show, Atack would pose for lads mags photoshoots – which she enjoyed but never thought of as “overtly sexual” – which in turn led to years of extensive online bullying, harassment and cyber-flashing. “I naively didn’t think what narrative was being painted for me,” Atack says. “People go, ‘How can you not expect it? You’re stood up there in your pants, going, ‘Look at me!’ But in my head, I wasn’t doing that. Genuinely, I was just doing a photoshoot to promote my work.” It took years for Atack to rewrite the narrative, to prove she was more than just a bit of “totty” who deserved the sexist abuse that was being hurled at her (a topic she explored in 2020 BBC documentary Asking For It).

But if you thought it was only lad mag culture that necessitated having to navigate being simultaneously sexualised and undermined by the media and general public, think again. Joan Bakewell, the 91-year-old broadcaster, recently revealed that she regretted being known as “the thinking man’s crumpet” in the 1960s. The moniker meant she was judged on her appearance rather than her intellect or talent, reduced to a “frivolous girl with short skirts”.

It didn’t make me feel that what I cared about mattered, which was ideas, people, conversation...

Joan Bakewell

“I was one of the first few women to be on television,” she said. “And with it goes the attention of Fleet Street, which is not particularly attractive, and I got a label which had stuck with me for quite a long time until I got too old for it.”

While she brushed off the comments on her looks and fashion choices, Bakewell admitted that “it didn’t make me feel that what I cared about mattered, which was ideas, people, conversation, the benefits of television, the good it could do, the good we could do in the world”.

The attention was focused, instead, “where I didn’t want it to be”, but the Labour peer felt compelled to “put up with it” without complaint. These days, she said, young women would fight back and say, “That’s damaging my career.” Atack speaking out seems to be proof that that’s true.

There’s something uniquely depressing about seeing two women, who rose to fame 40 years apart, share the same experience of being devalued because of their appearance. There’s also something uniquely depressing about realising how little things have changed, and that the issue of degrading and belittling women seems curiously timeless. Though beauty standards may alter, they always remain unattainable – and while women may be complimented on their looks, it’s often one side of the same coin that seeks to tear them down.

“Men are so angry with sexy women,” Atack concludes. “It’s like, ‘We’ll give you a little bit of power, but not too much. Here, you look nice on this front cover, but also, you’re a fat, ugly pig.’” As she identifies, whether you’re a well-regarded performer, broadcaster or indeed any woman audacious enough to step into the spotlight: “Misogyny isn’t going anywhere.”

Africana55 Radio

Africana55 Radio