This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

When the gunshots rang out, Dansira Karikumutima jumped to her feet.

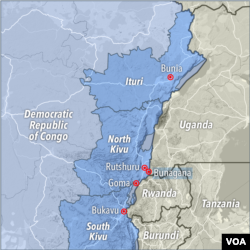

“I ran away with my family,” she said of the March day that M23 rebels arrived in Cheya, her village in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo’s North Kivu province. “We scattered, each running in a different direction out of fear.”

Months later, the 52-year-old, her husband and their 11 children have regrouped in an informal camp in Rutshuru town, where they’re spending nights in a schoolhouse and scavenging for food by day.

They’re among the latest victims of rising volatility in the eastern DRC. If unchecked, the unrest “risks reigniting interstate conflict in the Great Lakes region,” as the Africa Center for Strategic Studies warned in a late June report on the worsening security situation.

M23 is among more than 100 armed groups operating in the eastern DRC, an unsettled region where conflict has raged for decades but is escalating, especially in recent months. Nearly 8,000 people have died violently since 2017, according to the Kivu Security Tracker, which monitors conflict and human rights violations. More than 5.5 million people have been displaced — 700,000 just this year, according to the United Nations.

The Norwegian Refugee Council identified the DRC as the world’s most overlooked, under-addressed refugee crisis in 2021, a sorry distinction it also held in 2020 and 2017.

Fueling the insecurity: a complicated brew of geopolitics, ethnic and national rivalries and competition for control of eastern DRC’s abundant natural resources.

The fighting has ramped up tensions between the DRC and neighboring Rwanda, some of which linger from the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, where ethnic Hutus killed roughly 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus. Competition for resources and influence in DRC also has sharpened longstanding rivalries between Rwanda and Uganda.

How does M23 fit in?

The DRC and its president, Felix Tshisekedi, accuse Rwanda of supporting M23, the main rebel group battling the Congolese army in eastern DRC. M23’s leaders include some ethnic Tutsis.

M23, short for the March 23 Movement, takes its name from a failed 2009 peace deal between the Congolese government and a now-defunct rebel group that had split off from the Congolese army and seized control of North Kivu’s provincial capital, Goma, in 2012. The group was pushed back the next year by the Congolese army and special forces of the U.N. Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO).

Rwanda and its president, Paul Kagame, accuse the DRC and its army of backing the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR), a Congo-based mainly Hutu rebel group that includes some fighters who were involved in the genocide.

What sparked the resurgent crisis?

Last November, M23 rebels struck at several Congolese army positions in North Kivu, near the borders with Uganda and Rwanda. The rebels have made advances that include the overrunning of a Congolese military base in May and taking control of Bunagana, a trading town near the border with Uganda, in June.

Bintou Keita, who as head of MONUSCO is the top U.N. official in the DRC warned in June that M23 posed a growing threat to civilians and soon might overpower the mission’s 16,000 troops and police.

M23’s renewed attacks aim “to pressure the Congolese government to answer their demands,” said Jason Stearns, head of the Congo Research Group at New York University, in a June briefing with the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

The rebels want implementation of a 2013 pact known as the Nairobi agreement, signed with the DRC government, that would grant them amnesty and reintegrate them into the Congolese army or civilian life.

How is Uganda involved?

“The longstanding rivalry between Uganda and Rwanda in the DRC and the Great Lakes region is a key driver of the current crisis,” the Africa Center observed in its report. It cited a “profound level of mistrust at all levels — between the DRC and its neighbors, particularly Rwanda, Uganda and Burundi, as well as between all of these neighbors.”

Late last November, Uganda and the DRC began a joint military operation in North Kivu to hunt down the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), an armed group of Ugandan rebels affiliated with the Islamic State and designated by the U.S. government as a terrorist organization. Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni has blamed ADF for suicide attacks in Kampala last October and November.

Ugandan officials have accused Rwanda of using M23 to thwart its efforts against ADF, the Africa Center report noted, adding that the U.N. also “has implicated Uganda with aiding M23.” U.N. investigators a decade earlier had claimed credible evidence of Rwandan involvement.

Stearns, of the Congo Research Group, said the joint Ugandan-DRC military operation created “geopolitical ripple effects in the region,” with Rwanda essentially complaining that Uganda’s intervention “encroaches” on its sphere of interest in eastern Congo.

What economic factors are at play?

Some of the fighting is over control of eastern DRC’s vast natural resources, including diamonds, gold, copper and timber. The country has other minerals — cobalt and coltan — needed for batteries to power cellphones, other electronics and aircraft.

“The DRC produces more than 70% of the world’s cobalt” and “holds 60% of the planet’s coltan reserves,” the industry website Mining Technology reported in February, speculating that the DRC “could become the Saudi Arabia of the electric vehicle age.”

The Africa Center report noted there is “ample evidence to suggest that Ugandan- and Rwandan-backed rebel factions — including M23 — control strategic but informal supply chains running from mines in the Kivus into the two countries.” It said the groups use the proceeds from trafficked goods “to buy weapons, recruit and control artisanal miners, and pay corrupt Congolese customs and border officials as well as soldiers and police.”

Access also has value. In late 2019, a three-way deal was signed to extend Tanzania’s standard gauge railway through Burundi to DRC, giving the latter two countries access to Tanzania’s Indian Ocean seaport at Dar es Salaam.

And in June 2021, DRC’s Tshisekedi and Uganda’s Museveni presided over groundbreaking of the first of three roads linking the countries. The project is expected to increase the two countries’ trade volume and cross-border transparency, and to strengthen relations through “infrastructure diplomacy,” The East African reported. The project includes a road connecting Goma’s port on Lake Kivu with the border town of Bunagana.

“Rwanda, in between Uganda and Burundi, sees all this happening and feels that it’s being sidelined, feels that it’s being marginalized,” Stearns said in the CSIS briefing.

Rwanda has had its own deals with the DRC — including flying RwandAir routes and processing gold mined in Congo —but the Congolese government suspended all trade agreements in mid-June.

What can be done to address the crisis?

The DRC, accepted this spring into the East African Community regional bloc, agreed to the community’s call in June for a Kenya-led regional security force to protect civilians and forcibly disarm combatants who do not willingly put down their weapons.

No date has been set for the force’s deployment.

The 59-year-old Tshisekedi, who is up for re-election in 2023, has said Rwanda cannot be part of the security force.

Rwandan President Paul Kagame, 64, told the Rwanda Broadcasting Agency he has “no problem” with that.

The two leaders, at a July 6 meeting in Angola’s capital, agreed to a “de-escalation process” over fighting in the DRC. The diplomatic roadmap called for ceasing hostilities and for M23’s immediate withdrawal.

But fighting broke out the next day between M23 and the Congolese army in North Kivu’s Rutshuru territory.

Speaking for the M23 rebels, Major Willy Ngoma told VOA’s Swahili Service that his group did not recognize the pact.

“We signed an agreement with President Tshisekedi and Congo government,” Ngoma said, referring to the 2013 pact, “and we are ready to talk with the government. Whatever they are saying — that we stop fighting and we leave eastern DRC — where do you want us to go? We are Congolese. We cannot go into exile again. … We are fighting for our rights as Congolese.”

Congo’s government says it wants M23 out of the DRC before peace talks resume.

Paul Nantulya, an Africa Center research associate who contributed to its analysis, predicted it would “take time to resolve the long-running tensions between Rwanda and the DRC.”

In written observations shared with VOA by email, he called for “a verifiable and enforceable conflict reduction initiative between Congo and its neighbors — starting with Rwanda” and “an inclusive democratization process in Congo.”

Rwanda’s ambassador to the DRC, Vincent Karega, warned in a June interview with the VOA’s Central Africa Service that hate speech is fanning the conflict. Citing past genocides, he urged “that the whole world points a finger toward it and makes sure that it is stopped before the worst comes to the worst.”

Etienne Karekezi, Geoffrey Mutagoma, Venuste Nshimiyimana, Austere Malivika and Margaret Besheer contributed to this report.

Africana55 Radio

Africana55 Radio