This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

When museums in the UK start to reopen next month it will be to a new world: not just one of social distancing and mask-wearing, but one possibly entering a different cultural epoch.

The death of the African-American George Floyd was followed by global protests for social justice and racial equality. Anger directed at statues memorialising controversial individuals from Britain's colonial past has put a spotlight on museums and their collections, in what some are seeing as a generational shift in attitudes.

Many museums have expressed solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement, but what actions will follow the words for those institutions with links to Britain's imperial past?

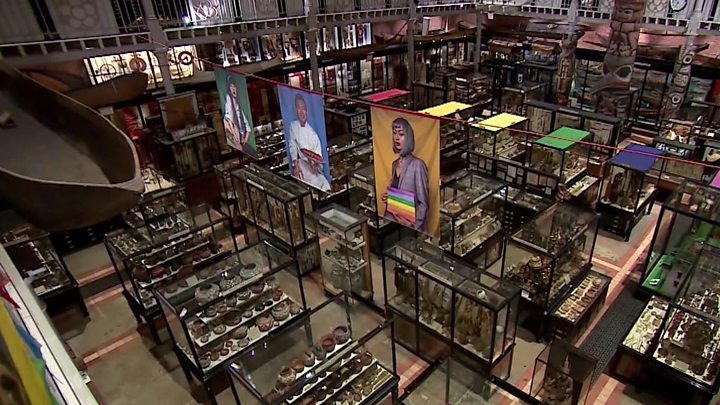

Professor Dan Hicks is a senior curator at the Pitt Rivers museum in Oxford, a sprawling anthropological collection containing around 600,000 objects from just about every country on the planet.

It was shortlisted for the prestigious Museum of the Year award 12 months ago, an accolade bestowed, in part, for the revisionist work Hicks has been conducting on the Pitt Rivers collection for the past four years.

Hicks and his colleagues have been re-evaluating, re-contextualising and re-presenting many objects from the perspective of the culture from which they came, as opposed to that of the white, British, Victorian man whose ethnographic collection founded the museum.

Hicks is a leading voice among museum professionals calling for the return (restitution) of contested cultural objects that are currently held in the UK's national and local municipal collections.

The most problematic artefacts, he says, are those stolen, looted or removed by the British from their place of origin where the local people had been subjugated.

"In this country you're never more than 150 miles away from a looted African object," Hicks says.

The UK's museums have received restitution requests from Australia, Asia and South America. But it is those from Africa that are coming under the greatest scrutiny, according to Hicks.

"We need to think very hard about objects [from Africa]. Where it is clear they were taken as trophies of war and however well you rewrite labels and re-tell history, you're not going to be able to tell a story other than one about military victory. In those cases, we need to work towards a restitution process."

Hicks says he is confronting the uncomfortable truths of colonial Britain and an empire built on slavery and the suppression of indigenous peoples across the globe.

There are some potential visitors within the catchment area of the Pitt Rivers, he reports, who have told him they will not set foot inside the museum because it is "too violent" - a reference to objects on display that were taken as spoils of war.

"This is very specifically about a period of time when our anthropology museums were used for purposes of institutional racism, race science, the display of white supremacy. At this moment in history, it could not be more urgent to remove such icons from our institutions."

Of these, the so-called Benin Bronzes, or Benin treasures, are the most high-profile example of looted artefacts, taken by British soldiers following a punitive and murderous raid on the ancient Kingdom of Benin (in modern-day Nigeria) in 1897.

There is no question in Hicks's mind that the Benin Bronzes should be returned. It is a point of view shared by the British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare, who thinks those held by the British Museum should be 3D-printed and displayed in London, while the originals are returned to Nigeria.

"It is a matter of respect and being treated equally. If you steal people's heritage you're stealing their psychology, and you need to return it," he says.

Hartwig Fischer, director of the British Museum, does not agree. While he accepts that a request has been made by Nigeria for the return of the Bronzes, he doesn't believe their ownership should be transferred back.

He thinks a better way forward is through a close collaboration between the British Museum and its counterparts in Nigeria, to whom he would loan the Benin Bronzes for long periods of time.

This is a conversation that is currently in progress and would include, he says, a broader exchange of ideas and knowledge.

The playwright Bonnie Greer was the deputy chair of the British Museum for four years and is familiar with the controversy surrounding the Benin Bronzes.

"I'm comfortable with them there [in the British Museum]," she says. "What they do for me, as a descendant of enslaved people, is they give me comfort and a link.

"I look at them and I can see myself… What I find when I see African objects in a Western museum... I get solace."

Greer does not think the Benin Bronzes should necessarily be at the British Museum in perpetuity, saying that the museums across the country should "be like dancers on their toes, ready to tell the truth, ready to listen, to have a door open".

A greater diversity of opinion and interpretation is required throughout the country's museums, she adds.

"Diversity isn't just putting black or people of colour in institutions. Listen to them, implement what they say… There are plenty of people who teach black history, who know heck of a lot.

"Bring them in, let them hold courses and have clashing interpretations of an object."

Sara Wajid is head of engagement at the Museum of London and a member of Museum Detox, a network of people of colour who work in museums. She says there is very little diversity in senior positions in the UK's cultural institutions.

"In most museums the place where you see black staff is in cleaning and security. You won't see them in curatorial departments, you won't see them in management.

"So, the first step towards a decolonised museum is where you have BAME leadership."

The British Museum bears her argument out. Fischer describes it as a museum of the world but admits there are no black curators among a curatorial staff of around 150. It is, he says, "a big issue we need to address."

Shonibare thinks that the lack of black curators at the British Museum is unacceptable. "There are plenty of people qualified to do that job, and I think that's the kind of thing the museum should be looking at. You know, if black lives really mattered then they will take those issues really seriously."

Fischer agrees, while also saying that museums in the UK are heading in the right direction. He considers Britain to be "at the forefront of making museums inclusive", having already made "a vast contribution to reaching out to… address various communities."

As with several of the UK's cultural institutions, the British Museum is the product of the country's colonial past, including its participation in the slave trade.

The Bloomsbury-based institution was founded on the collection of Sir Hans Sloane, a man whose great wealth came mainly from a slave plantation in the West Indies.

The vast sums of money the Jamaican enterprise generated enabled him to acquire so many valuable objects that when he died, the 71,000 plus items he had amassed formed the basis of not only the British Museum's collection, but also that of the Natural History Museum in South Kensington.

"The historical fact we have to deal with is that slavery has been an integral part of the European economy for centuries" Fischer says. "That is something that needs acknowledging and it needs to be addressed.

"We need to widen the scope, we need to deepen the work and look at the history of our institution as a whole."

Shonibare agrees. "We live in a multicultural world, museums should reflect that history and that story. How did we get here? Where did the wealth come from? It's absolutely important that museums do that work of representation."

The artist thinks the death of George Floyd and subsequent protests are the beginning of a new movement that will see change in society, a point of view with which Fischer concurs.

'Astonishing' conversations

"What we are witnessing is a huge shift in perception, and [the] addressing [of] a very great problem, which is racism and that needs to be addressed."

He thinks his museum can and needs to be do more, but says change doesn't take place overnight. According to Wajid, though, it is happening.

"Some very serious and unusually frank conversations have been taking place between BAME museum staff networks and managers and leaders - most of whom are white - about their stance with regards to Black Lives Matter, to anti-racism, and to the work of decolonising museum collections.

"I've been working and campaigning towards greater equality in the culture sector for the past 25 years, and the kind of honesty and deeply uncomfortable conversations that I've heard [over the past three weeks] are astonishing."

Hicks has also seen a change in attitude. "There's a generational shift going on around arts and culture and heritage. It was acceptable, maybe a generation ago, to talk about loans and facing up to Empire, using these objects to tell the story better.

"There's a new generation now who really don't buy that - who see the museum as an end point as an outdated idea. In no part of arts and culture should we think that our museums are unable to evolve and to change."

Follow us on Facebook, or on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk.

Africana55 Radio

Africana55 Radio