This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Support truly

independent journalism

Our mission is to deliver unbiased, fact-based reporting that holds power to account and exposes the truth.

Whether $5 or $50, every contribution counts.

Support us to deliver journalism without an agenda.

Louise Thomas

Editor

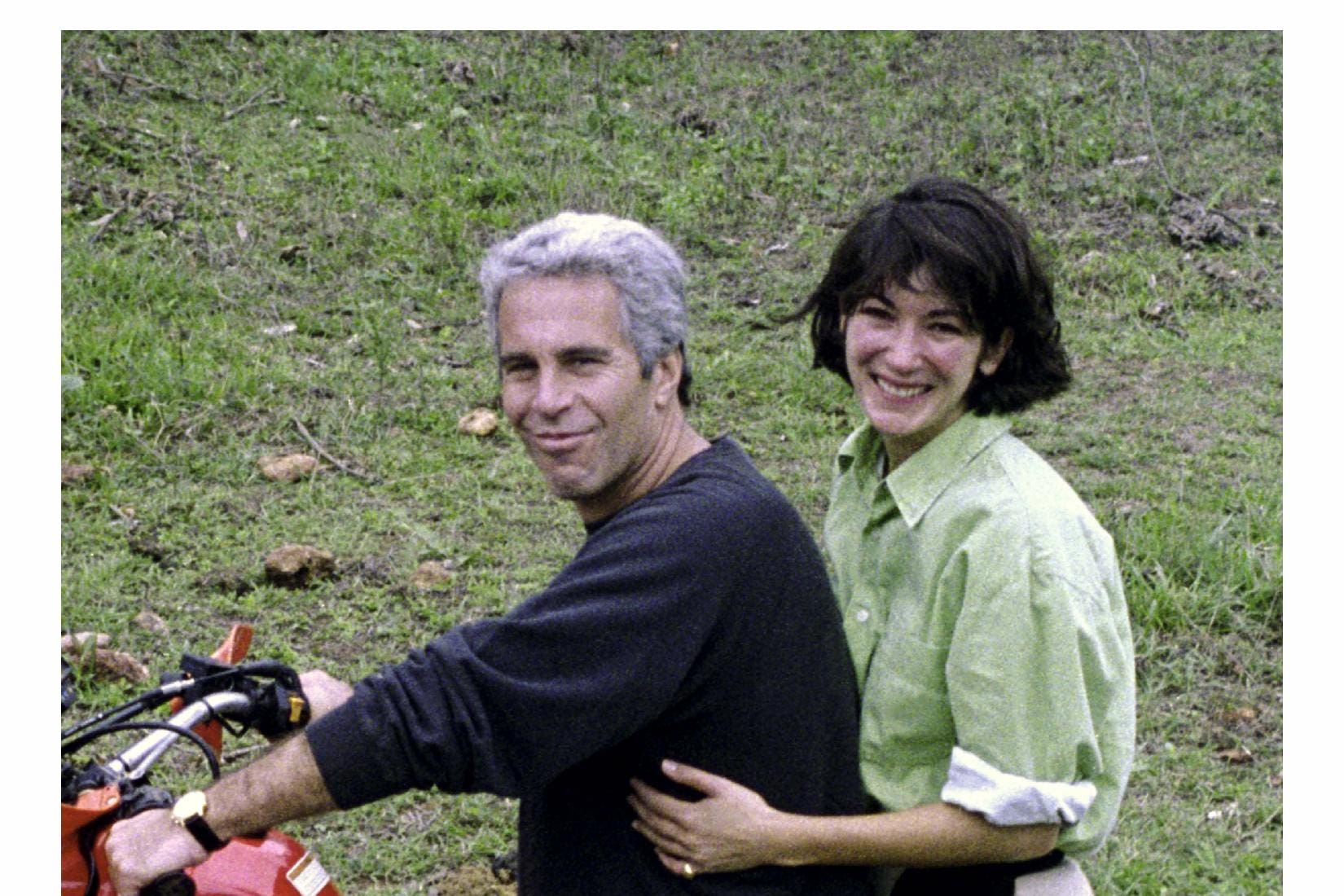

She was treated better than the victims – there’s no question.” Lucia Osborne-Crowley, a journalist and author of new book The Lasting Harm, is talking about Ghislaine Maxwell. Specifically, about Ghislaine Maxwell during her child sex trafficking trial. She was facing charges for six federal crimes and yet, claims Osborne-Crowley, the now-convicted sex trafficker and former girlfriend of the late Jeffrey Epstein was given a lot more dignity throughout that process than her victims.

From 29 November to 29 December 2021, Maxwell was brought into the courtroom each day by two young, female guards, with whom she would laugh and joke and “seemed to have a great relationship”. She was allowed to move back towards the gallery and speak with her family “at length” in the courtroom; she was treated as if being charged “for a fairly minor offence”, Osborne-Crowley says – not one of the most serious crimes imaginable. More shockingly still, her family were given priority over Maxwell’s victims. They had reserved seats every day while women who had allegedly suffered at the hands of Epstein were forced to queue outside the courthouse in the cold for hours, only to be told there was no room left for them.

“It was really, really shocking,” says Osborne-Crowley. “This was the only trial. This was the only thing that has happened to offer a shred of justice. And even then, the courts managed to take that away from the victims by treating them so badly during the court process.”

She cites the day that one woman had to leave, triggered and re-traumatised, because a male security guard started “yelling” about her right to be there, insisting that she hadn’t arrived early enough to secure a spot. Osborne-Crowley tried to offer her seat instead, but the guard point-blank refused to let the two women switch. “This is after she’s been trying to sit in on her own abuser’s trial, the one chance to give the victims some dignity. After all they’ve been through, the very least that the courts and the US government prosecuting the case could have done is make them comfortable and look after their wellbeing during this trial. They completely failed to do that.”

Osborne-Crowley, a seasoned court reporter, has attended countless trials during her career. Never has one required quite so much of her; never has one struck such a deep connection. When she first heard that Maxwell would be tried for her involvement in a sex trafficking ring involving some of the world’s most powerful players and spanning decades of abuse, she knew she had to be in that courtroom every single day to bear witness.

Because, for her, this case was personal. Osborne-Crowley was herself sexually abused as a child and teenager. First groomed by her gymnastics coach and later repeatedly raped by a stranger at knifepoint while on a night out, she knows first hand how “poor” the justice system is when it comes to understanding these kinds of crimes. She’s also written two previous books on sexual trauma: I Choose Elena and My Body Keeps Your Secrets.

“I have always been interested in the law and the justice system, but my personal experience with this particular kind of trauma gave me that push to be really invested in this trial,” she tells me. “And I think that ended up being much more necessary than I thought, because this trial was a real test of resilience.”

Physically, as well as mentally – only four journalists were allowed in each morning, gaining entry on a first-come, first-served basis, while the rest were siphoned off into side rooms to watch on grainy televisions. Competition for these spots was fierce, and usually involved setting an alarm for 11pm, getting to the Manhattan courthouse for midnight or 1am, and waiting for eight hours amid the bitterly cold New York winter. It was not for the faint-hearted.

This tenacity paid off though, and Osborne-Crowley was in the main courtroom every day of the five-week trial, barring the first one (she had arrived “late” that day, at 3am). Maxwell even started recognising her – at one point very obviously making a sketch of her on a pad of paper. “She is a very intense presence in a room,” says Osborne-Crowley. “She would try and interact with us in small ways throughout the trial.”

Another reason Osborne-Crowley was so determined to see this trial through from start to finish was that she knew it would be groundbreaking in raising global awareness of concepts like organised grooming, child sexual abuse, delayed disclosure (where victims don’t come forward until they’re much older), shame, and “all of the things around sexual abuse that we still struggle to understand”.

What she wasn’t expecting was that the victims who were brave enough to come forward and testify would be aggressively and mercilessly hauled over the coals – as if it were them, not Maxwell, being put on trial.

It was absolutely appalling; I have covered many trials, and it’s hard to shock me

“It was absolutely appalling,” she says. “I have covered many trials, and it’s hard to shock me. I know how badly these victims are treated in cross-examination. I know how the system is stacked against them. But it was something else to see this in real time. It was difficult to watch.”

She tells me the defence team were “absolutely ruthless and nasty”, recalling how one witness who had become an actor as an adult was constantly questioned about her career – “your job is to make up stories, right?” – while another’s opioid addiction was used against her. “One of the witnesses was very open about the fact that when she was very young, when she was starting to be abused and trafficked, she started to rely on opioids to help her get through these sessions of abuse. And she said very clearly and very honestly to the jury, ‘I did this because I couldn’t handle what was happening to me’. That was an amazingly brave thing for her to say.”

But this admission was followed up by an interminable interrogation about her substance abuse. At one point, the defence lawyer levelled the accusation: “You’re just a drug addict. Why should we believe you?” It’s a line of questioning that completely misses the point, argues Osborne-Crowley, and in fact neatly encapsulates so much of what’s wrong with the current way in which survivors are stigmatised by the legal system.

“The very symptoms of childhood abuse end up being used to discredit victims of childhood abuse on the witness stand,” she says. These include substance abuse and other addictions, eating disorders, self-harm, delayed disclosure and traumatic memory. This last refers to the way in which memories of traumatic events are stored in the brain and expressed differently to “normal” memories. Studies have shown that traumatic memories are often disjointed and fragmented, characterised by very vivid recollections of the event, such as sensory details, but are difficult to put into coherent speech and chronological order.

“All of these things we know, neuro-scientifically, are symptoms of abuse,” adds Osborne-Crowley. “If anything, they’re proof that this did happen to these people. But we still live in a world where they are used to try and convince a jury that these victims are not credible, are not to be trusted – and that is just so deeply unfair and unscientific and untruthful. I’d like that to change.”

All of these symptoms were used against the victims who testified in the Maxwell trial: failure to speak up when they were children, drug use, misremembering of very specific details. In one instance, a discrepancy in whether the witness was first approached at the age of 14 by Maxwell walking a dog and later joined by Epstein, or first approached by Epstein and then later joined by Maxwell walking a dog, was used against her. The defence team’s tactic was to suggest that, if minute details like this couldn’t be relied upon 28 years later, all this woman’s memories should be called into question. But as Osborne-Crowley writes in The Lasting Harm, “The key details remain the same in each telling: the setting, the couple, the dog.”

For those unfamiliar with traumatic memory, the presentation of “inconsistencies” can easily be taken as evidence that someone is lying – despite scientific evidence to the contrary. Osborne-Crowley was stunned when some of her (older, male) fellow reporters who were also present in the courtroom accepted the defence’s argument as fact. “That’s pretty damning, that thing about the dog. That really does make it seem like a lie,” said one. “That’s way too many inconsistencies,” said another. It highlighted the way in which a lack of direct or indirect experience can lead to a lack of understanding when it comes to the complex nuances surrounding grooming and sexual abuse.

The issue of personal experience has led to some unexpected repercussions since the Maxwell trial ended. She was convicted of five out of six counts of sex trafficking and sentenced to 20 years’ imprisonment. In the wake of the verdict and sentencing, however, one jury member, Scotty David, stepped forward and voluntarily shared that he too had been abused as a child. Osborne-Crowley reported the exclusive interview for The Independent, in which he explained that he had gone into the process believing in Maxwell’s innocence. The overwhelming evidence to the contrary changed his mind. His own history of abuse, said David, meant he was able to educate the other jurors on how traumatic memory works.

The story was used by Maxwell’s team to appeal her conviction; the juror in question had mistakenly failed to disclose his own abuse experience on a pre-trial questionnaire. The appeal was heard on 12 March 2024, and the outcome has yet to be announced.

The very symptoms of childhood abuse end up being used to discredit victims on the witness stand

Osborne-Crowley feels, understandably, “torn up” and “conflicted” about the part she has played in this appeal. But ultimately, she believes it is her journalistic duty to tell people’s stories. David wanted his story to be told, so she told it. The victims of Maxwell and Epstein wanted their stories to be told, so she wrote a book about them. Not a book about the darkly glamorous elements of this case that usually steal the spotlight – the private jets and famous names and billionaires – but the desperately sad tales of women whose lives were unfairly blighted by the abhorrent actions of a serial abuser. They are still living with the consequences of that abuse. They always will be. These are the people whose voices deserve to be heard after being silenced for so long.

Whatever the result of Maxwell’s appeal, Osborne-Crowley will accept it. But she hopes, if nothing else, that this trial has shone a light on how much a currently broken system must change for victims.

“The way that these crimes are dealt with by the justice system needs to be completely overhauled,” she says simply. “The lasting effects of trauma produce the precise symptoms that are used to undermine victims and witnesses, and that process of undermining them and disbelieving them is retraumatising.” It’s a vicious cycle where victims who are working up the courage to come forward are stuck in a lose-lose situation; the system is setting them up to fail “by having these ideas about credibility that simply do not apply to traumatised victims”.

“It’s time that we have different rules for victims of childhood sexual offences,” says Osborne-Crowley. “At the moment, they are being treated like victims of any other crime, and it just doesn’t work. It doesn’t make scientific sense. And, ultimately, it’s getting in the way of justice.”

The Lasting Harm, published by Fourth Estate, is out now

Africana55 Radio

Africana55 Radio