This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

The red on beige sign outside La Torre shop advertises the kind of underwear earlier generations might have worn, mostly knickerbockers and girdles.

The shop — known as The Tower in English — has been a standard in Barcelona for more than 120 years, preserving a glimpse into the city's past.

La Torre has withstood the relentless march of Starbucks, McDonald’s, and other international corporate chains which, critics say, have eaten up the souls of downtowns. Other period shops, cinemas or libraries have not been so fortunate and have been forced to close.

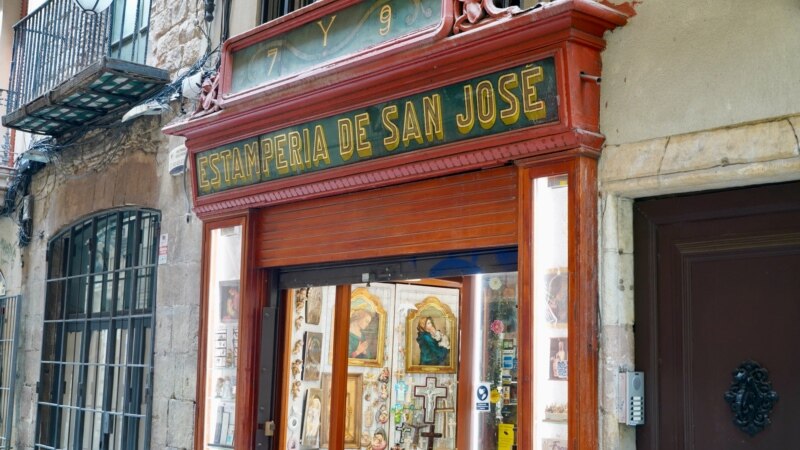

Campaigners in Spain are determined to safeguard a form of heritage which they say is increasingly under threat: the shop signs which advertise small businesses often run by families.

Described as the “Indiana Jones of the Lost Shop Signs” by the Spanish newspaper ABC, they advocate for everything from the Art Deco cinema signs, old-fashioned flashing Buy Easy signs and the ornate golden shoe shop signs.

The commercial signs outside shops that have long shaped the identity of cities, towns and villages are a part of our past, said volunteers from the Iberian Network in Defense of Graphic Heritage, a collective of about 50 projects across Spain.

Heritage

To most people, heritage sums up the idea of castles, priceless paintings, and royal jewels. But these campaigners contend that the urban landscape which most people inhabit every day is as much a part of our treasured past too.

Heritage legislation in Spain protects everything from cathedrals to castles to bullfighting but not shop signs – so far. So, campaigners must first convince local councils to protect these symbols of everyday life.

“We are against nostalgia because it says that the past is better than the present or the future. We want to preserve these shop signs because they represent something from the past that we can use to learn about for the future,” Alberto Nanclares, of the Iberian Network, told VOA in an interview.

Nanclares said the organization began in 2014 after the then government abolished a law which guaranteed cheap rents to companies, driving many small shops out of business. He said they plan to open a museum to show off the signs they have saved.

“It should be very popular because it will attract designers, architects, elderly people who want to see the past and people who want to take their grandparents to see the place where they grew up,” he added.

Laura Asensio is a graphic designer who has been working for an organization called Valladolid with Character. They hope to stop Valladolid, a northern Spanish, from becoming a bland version of many other cities across Europe.

Volunteers are mapping out the old shop signs which have been saved or at risk from being lost.

Asensio said she hopes to convince the city council to change local laws to preserve this part of the city's heritage. A book will be published with photographs in December detailing this part of the city life for future generations.

“The reason we started this organization is to stop shop signs from being lost to globalization. All over Europe, city centers are being dominated by McDonalds, Zara, or Burger King,” she told VOA.

Laura Aseguradade, an interior designer, and member of the Iberian Network, said younger people may not appreciate the value of the architectural heritage of their own cities.

“But if you don't value traditions and distinctiveness of your cities then Madrid ends up looking much like Barcelona or London with the same chains springing up due to globalization,” she told VOA from her home in Madrid.

“We are not against globalization, but the architectural heritage brings value to your city because it makes it different to other places which is important for tourism and the quality of life.”

Africana55 Radio

Africana55 Radio