This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

It is not widely known that many Australian colonial natural history collections are represented in German museums and herbaria, nor that there are initiatives to transform these artefacts of colonial heritage and science back into objects from living cultures with living custodians and their own stories to tell.

Dr Johann August Ludwig Preiss (1811–1883) played a significant role in this evolving story as the first professional botanist to collect systematically in the Colony of Western Australia from 1838 to 1842.

His collections of flora and fauna were pivotal in opening this globally significant region of biodiversity to the world – and he beat the British at their own game by bringing their new colony’s botanical wonder to scientists, nurserymen and gardeners in Europe.

Despite his unusually long sojourn collecting in Western Australia, Preiss has been largely forgotten – unlike his contemporary, the naturalist and explorer Ludwig Leichhardt (1813–1848), well known for his work in northern and eastern Australia and his ill-fated 1848 expedition to cross the continent; and the globally active science visionary Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859), whose birth anniversaries were celebrated in Germany and Australia in 2013 and 2019 respectively.

Preiss held no important posts in exploration, science or public office and left only a small selection of archived letters and some strangers’ impressions. So, we are left to speculate about the negative spaces between the known fragments of Preiss’s life and the agents – human and non-human – of the worlds he moved through.

The natural sciences in Germany and Britain in the 19th century shared much common ground: there were royal dynastic connections, cultural ties, migrations to Australia and complementary interests in advancing the natural sciences.

The British empire, however, had the edge over Germany, with global networks plugged into the nerve centre of the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew – an oasis of collecting, classifying, storing, propagating and dispersing exotic and useful plants in Britain and the colonies.

Germany had more diffuse networks of scientists, across scattered institutions – universities, herbaria and botanical gardens – focused on classifying and documenting the diversity of flora and fauna into rigid systems, using dried, preserved and some live specimens.

In Preiss’s time Germany had no colonies to draw on but collected on others’ turf. In British colonies this seemingly innocent practice was supported by their structures of privilege and violence.

While there were no legal prohibitions on German naturalists collecting in British colonies, Preiss irritated his hosts by staying so long, collecting so much and transporting most of it back to Germany, not London.

Preiss came from humble origins in the small village of Herzberg am Harz, in the Harz mountains of the Gottingen district of Lower Saxony. When I visited there in 2018 to learn about Preiss’s family and early life, the council archivist Dieter Karl Wolfe explained there was little local information known about his family.

Preiss was the eldest surviving son of 12 children, and his father was a master saddler (like his father before him), a vinegar brewer and land owner. His cousin Gustav Friedrich Preiss (1825–1888) was the family success: he printed the local daily newspaper Kreiss Zeitung from 1848, became the village mayor and built a fine home. There are portraits of him and his wife in the council archive.

Another more internationally minded relative helped start the town’s Esperanto Society in the early 1900s. Friendly Esparantists showed me public monuments for Esperanto and its Polish founder, Ludwik Zamenhof (1859–1917) – but there was nothing to commemorate Preiss, their local botanical achiever.

Speculating on why Preiss took up botanising in far distant lands, Wolfe extolled the benefits of Germany’s advanced education system for gifted youths of limited means – like Preiss and Leichhardt.

The ideal was a humanistic education to equip children with the foundations of learning and intellect, allowing students to build further knowledge and expertise in adult life. The curriculum included science and languages.

Preiss probably followed the same schooling trajectory as Leichhardt: boarding school, gymnasium, university. Preiss was university educated and held a German DPhil doctorate. This was more like a degree with an original research component than today’s formal doctorate qualification.

Preiss’s faculty “promoter” was probably Professor Johann Georg Christian Lehmann (1792–1860), director of Hamburg’s botanic garden, who sent Preiss to the Western Australian Colony.

The craze for botanising gripped both scholars and amateurs and opened new opportunities for serious study, teaching and collecting – assisted by new equipment, including the vasculum (a botanical tin case for collecting in the field), drying papers for preparing specimens, Wardian cases (ensuring safe transportation back to Europe) and glass houses for cultivating living plants.

In the 1830s, the botanical world was abuzz with news of Western Australia’s unique floral diversity. Transport of plants to London was still in its early days in 1836 when Lehmann first recognised the chance for expansion through the 25-year-old Preiss.

Preiss recalled being instructed to collect everything – flora, fauna, minerals and fossils – and hoped to “collect the products of [natural history] and arrange those products in a useful way for the purpose of science”.

Lehmann and his wealthy friend, Wilhelm von Winthem (1799–1847), a private collector and entomologist with extensive collections, organised funds for him through a form of venture capital under which the von Winthem family company publicised and sold shares to private citizens and collecting institutions.

On Preiss’s return, investors would choose items from his collections equal to the value of their shares.

Arriving in Perth in late 1838, a dusty village huddled between vast expanses of sea, bush and hinterland, Preiss encountered a parochial society.

Local collectors who worked with London’s botanical elite guarded their status jealously. Most colonists were disillusioned by false promises of rich farming lands and worn out by the struggle to survive.

I imagine Preiss as lonely and friendless.

The local landscape would have been so strange for Preiss, humanised by millennia of Nyungar curation but an apparent wilderness to the colonists’ eyes.

Botanical scientist Steve Hopper has revealed how the deep time of the region’s unusually stable environmental evolution both helped shape the unique floristic richness and endemism of this area and enhanced Nyungar people’s deep knowledge (kartijin) of their country – enabling them to live well off the diversity of plant foods they cultivated and nurtured with practices they adapted to the environment and passed down over many thousands of years.

This richness drew Preiss in.

Preiss began collecting immediately. In contrast to local British collectors he had the freedom of sufficient funds and no domestic encumbrances or civic duties. He also had no rights to own land.

His extensive collecting implicated him in the process of multispecies destruction and dispossession. The indigenous Nyungar people were already in a state of crisis as colonists destroyed their ancient accommodations to the land and replaced them with their own hasty adaptations of species and farming.

The destruction intensified during the 20th century with the clearing of 90 per cent of the region for wheat farming. In fewer than 200 years this encounter between Old and New World ecosystems transformed the landscapes of exceptional floral riches into a canary in the coalmine for climate change.

A new critical approach to Australian 19th century natural history collections in German institutions has been prompted by concerns about their colonial provenance and reports of environmental damage.

In 2018 in Berlin, curators and scholars attended an international conference on the politics of natural history and decolonising of collections and museums.

There were calls to open conversations with indigenous custodians and reflect on issues of climate change. Environmental knowledge in Preiss’s field notebooks, now missing, could have made an important contribution.

In a report on the colony published in Flora (1842), Preiss wrote that he “recorded [information] about specimens he observed and learned accurately from the Aborigines”.

The field books from his 1841 survey commission held in the State Records Office in Perth suggest the extent of the loss, being richly illustrated with botanical and landscape features and detailed annotations of measures and calculations.

They speak eloquently today of how seriously Preiss took this colonial project to map “the significance of the earth … as a space to be occupied”.

Preiss wrote that he “traversed this land in all directions … [and] observed the greatest diversity of plants”. It seems he had no transport or equipment for long surveys, so often walked lengthy distances alone.

This was an intimate way for Preiss to come to know the bush. His proximity to plants and the earth sharpened his eye for shapes and colours as well as his capacity to interpret signs along bush pathways. He sometimes travelled with colleagues, and visited Rottnest Island with the colony’s chief botanist James Drummond and John Gilbert, who collected for British ornithologist John Gould.

And he relied on the hospitality of homesteaders and assistance from Nyungar people. The colony’s advocate-general George Fletcher Moore noted an instance, perhaps disapprovingly, of Preiss walking out of the bush with a Nyungar woman, both of them loaded down with plants.

He added that “the natives seem quite surprised at his collecting the jilbah [shrubs] and are very curious to know what he does with them”, suggesting that Preiss was following the colonial practice of collecting without their permission.

Despite being the colony’s best qualified botanist, Preiss was never invited to join its British collecting networks. Instead, Preiss built his own networks in London and Germany.

Drummond became his occasional helper and nemesis. He warned his London patron, Sir William Hooker (1785–1865), that the new German botanist was collecting for the Russian, Prussian and some German states.

The German botanist Dr Ludwig Diels (1874–1945), who collected in the area in 1906, imagined the two men as benign opposites: the older “bushman, always in the saddle” out collecting rather than “arranging his specimens in order” and young Preiss, the “cultured scientist of old Europe” and first collector in the colony to have “each item in his collection carefully labelled, giving the locality and other data”.

However, simmering resentments erupted after Preiss challenged Drummond’s identification of a poison plant killing stock and quaffed an infusion of its leaves to prove his point. Preiss survived the ordeal but lost the argument after Drummond proved the plants’ toxicity for stock.

The more Preiss wore out his welcome in the colony, the more determined he became to stay and in 1839 he decided to try his luck as a British subject, with all the benefits and moral compromises this bestowed.

In 1839 he wrote to the colonial governor requesting naturalisation as a British subject, referring to British connections with the kingdom of Hanover near his birthplace.

He outlined his intention to return to Germany to raise funds for expeditions into the northern interior to explore, collect and open up the land and then become a farmer.

He proposed to sell his collections to the British government for £3,000 – “being produce of a British territory” – and added, “I flatter myself that such a collection has never been sent from this country to England” and there were many new species “not known in Britain and Europe”.

He also proposed a German immigration scheme to help resolve labour shortages in the colony, suggesting that 50 young farming families be enticed from Saxony and the Rhine province in a payback arrangement with other settlers and for his own farming needs, with government land grants payable for bringing out workers.

If his proposal was not accepted he would seek Prussian and Russian funding to explore the north coast.

The British government refused Preiss’s offers, preferring to acquire from established British collectors such as Gould and Gilbert. His request for naturalisation was finally granted in 1841. The next year he travelled back to Europe, taking with him the largest collection then to leave the colony.

Lauded at the time, Preiss’s actions of taking indigenous plant material and knowledge without consent for scientific gain would now be condemned as bio-piracy.

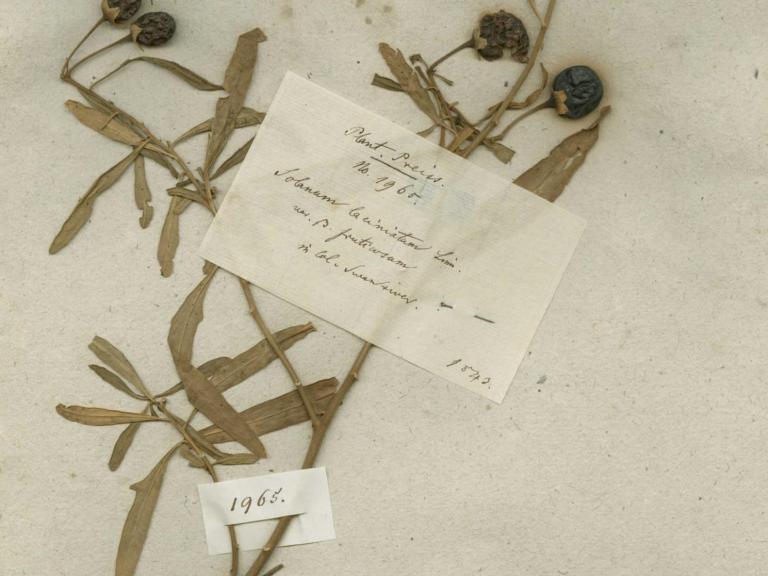

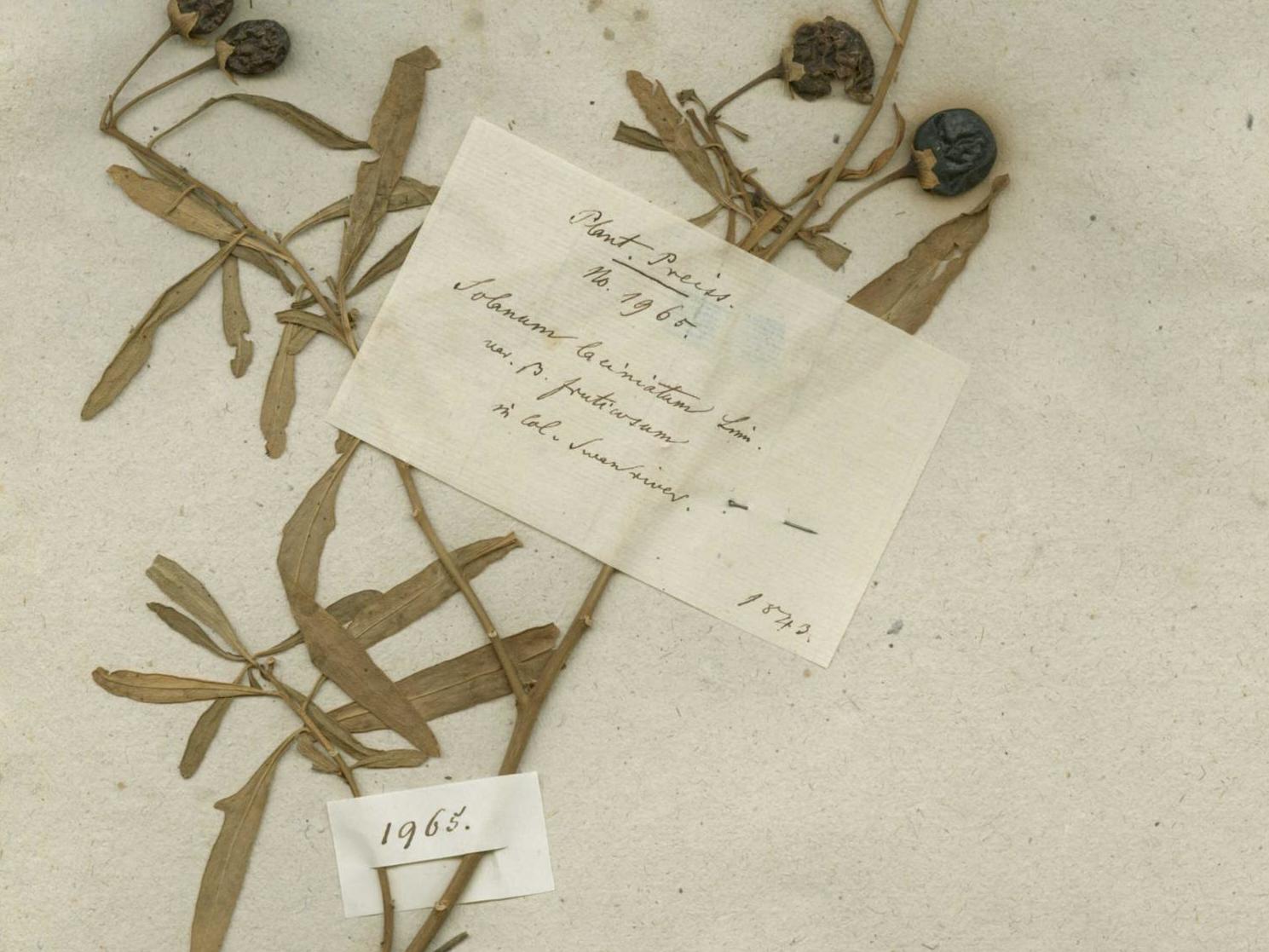

The collection included 200,000 plants with around 2,500 species and collections of algae, fungi, lichens, bryophytes as well as species of birds, reptiles, mammals, shells and more, as well as his copious notes.

Packed firmly in tin-lined boxes, they travelled well. Ironically, Preiss’s boxes left no space on board for Drummond’s collection of seeds and specimens to be sent to London. Delays in its passage meant that nurseries lost an entire season for planting – while Preiss’s quality collections and duplicate plants entirely spoiled the market for Drummond.

Diels lavishly praised Preiss’s collections for the sheer quantity of specimens he had collected in such a short period, the range of plant specimens, detailed information to identify flowers and plants and his collecting sites, the overall presentation that made his collections and notes so useful to science, and the outstanding achievement of producing the first West Australian collection for Europe’s leading herbaria.

Australian naturalist Rica Erikson (1908–2009) observed that his collections were “far superior to others being offered for sale in England”, but that British botanists “were prejudiced in favour of collectors of their own nationality”.

Preiss’s return to Germany via London was troubled – although he did manage to sell some plants and seeds to fund his journey across to Hamburg. But the situation he found there was disastrous.

The Great Fire of Hamburg in May 1842 had killed more than 50 people and destroyed many public and private buildings. The huge costs of rebuilding would cripple the state – and plans for the natural history museum that would have housed Preiss’s collections were shelved, along with their purchase.

Preiss was now forced to advertise the collections for sale – both to cover his debts from the trip and to offload the sheer quantity of material remaining after his investors’ selections.

He placed advertisements praising the excellence of his collections in botanical and gardening journals, wrote letters to institutions and private collectors, and published his report in the Flora with observations of natural features of the colony.

He also announced his intention to make a second longer journey in Australia from the Gulf of Carpentaria across country to the Swan River Colony. A portion of the current collections, he said, would be delivered to Lehmann “as soon as they are generally arranged, and … description and publication [entrusted] to him and other celebrated natural historians”.

Preiss’s expedition never eventuated, but the book hinted at in his report was a triumph. The two-volume publication named Plantae Preissianae (1844– 1847) was compiled by Lehmann with leading German botanists working from the collections, all with extensive publications on Australian species.

This was the first major reference book on Western Australian flora, and preceded by decades the British seven-volume Flora Australiensis (1863–1878) compiled by botanist George Bentham (1800–1884) – although that work, too, featured several of Preiss’s specimens.

There were further honours for Preiss: he was commemorated in the names of around 100 plants – a matter of considerable status; in 1843 he was elected to membership of the National Academy of Germany; and in the same year his name was added to the registry of the Regensburg Royal Botanical Society.

And his collections began their own journeys. Splitting them for sale dispersed them into private collections and an estimated 35 European herbaria, with the “original” or standard reference set of specimens for Plantae Preissianae passing from Lehmann to his widow, and eventually to its final resting place in the Lund herbarium in Sweden when Germany declined to buy it.

Preiss’s extensive zoological collections of mammals, birds, reptiles, insects and other material did not fare so well.

Some were sold to European museums or dealers but many simply disappeared or can no longer be identified as his. Credit for his “discoveries” of new species was given to other collectors.

His entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography laments that “had Preiss the backing of an ambitious and enterprising zoologist, as Gilbert had in Gould, it is certain that he would have been much better known today”.

Despite the success of the book and his standing among Europe’s natural historians, in 1843 Preiss suddenly announced that he was leaving Hamburg along with his collections – at the “urgent wishes of my father” – and that all future letters should be sent to him at Herzberg.

He gave no further explanation for this; in the modern parlance, it seems he just “left the building”.

This sudden shift by Preiss from a very public life to a very private one remains an unsolved mystery. Preiss’s legacy, however, is enduring.

His remarkable achievements in the few years between 1838 and 1843 created a permanent link between the botanical sciences in Western Australia and Germany. His sudden withdrawal opened a space for others to lead.

But how will the collections fare under the well-deserved critical scrutiny of their colonial origins and histories in German institutions? Can they be decolonised to take on new tasks relevant for today?

A couple of years ago, sitting with Preiss’s dryandra specimens at the Göttingen herbarium, I was inspired to see them as potential message sticks with agency to bring people together.

Now I’m part of a new project, Healing Land Healing People, based at Dryandra Woodlands south-east of Perth in the country of our project leader, Nyungar Elder Darryl Kickett.

We are working with the knowledge of Nyungar families, botanists, historians and artists to restore the biodiversity of the land and community cultural strengths. We work with similar projects at other sites in the south-west region.

In Germany we are linked with the Centre for Australian Studies at the University of Cologne and the Rachel Carson Center at the University of Munich. My role is to identify other collections from the region in European museums and herbaria and their curators.

With Nyungar Elders and curators sharing their knowledge and stories we can map the journeys of the message sticks from the sites where they were collected to their present locations.

With our German colleagues we can weave new narratives of biodiversity loss and restoration to engage the public, heal the past and ensure a future for our corner of Western Australia and other global biodiversity hotspots.

Anna Haebich is a senior research professor, at Curtin University. This article first appeared on The Conversation.

Africana55 Radio

Africana55 Radio