This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe death of former One Direction star Liam Payne has sparked a debate about the duty of care in the music industry, particularly for young people.

In one of the most powerful tributes to the singer, who died at the age of 31 after falling from a hotel in Argentina last week, TV personality and former X Factor judge Sharon Osbourne said: "We all let you down."

Osbourne said Payne was "just a kid" when he "entered one of the toughest industries in the world, and asked: "Who was in your corner? Where was this industry when you needed them?"

More than 25,000 people have now signed a petition saying the entertainment industry "needs to be held accountable and be responsible to the welfare of their artists".

Osbourne herself wasn't a judge when Payne found fame on the show - he first auditioned at the age of 14 in 2008 before returning two years later and becoming part of One Direction. The rest is history.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhile the boy band went on to achieve phenomenal success across the globe, Payne himself acknowledged that it came at a cost.

He admitted he used alcohol to cope with the level of fame "because there was no other way to get your head around what was going on".

US star Bruce Springsteen is among those who have now spoken about the negative impact of the pressures of fame in recent days.

He told the Daily Telegraph that "young people don't have the inner facility or the inner self yet to be able to protect themselves from a lot of the things that come with success and fame".

"So they get lost in a lot of the difficult and often pain-inducing [things]... whether it's drugs or alcohol to take some of that pressure off," he said.

"I understand this very well from my own experience, as I have done my own wrestling with different things."

Robbie Williams also acknowledged that he struggled with his own demons when he was 31. "By the grace of god and/or dumb luck I’m still here," he said.

The former Take That star called for more kindness and empathy from the public towards famous figures who might be going through difficulties. "Even famous strangers need your compassion," he wrote.

Could the music industry do more to help fledgling artists, and are things now changing?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesRobbie Williams' frequent collaborator, songwriter Guy Chambers, told the Observer the industry should hold back from working with performers who are under 18.

"I do think putting a 16-year-old in an adult world like that is potentially really damaging. Robbie experienced that, certainly," he said.

Chambers added: "I know in Robbie’s case, with Take That, there wasn’t any proper protection set up to look after what were teenage boys. That was a long time ago, but I don’t see much sign of change."

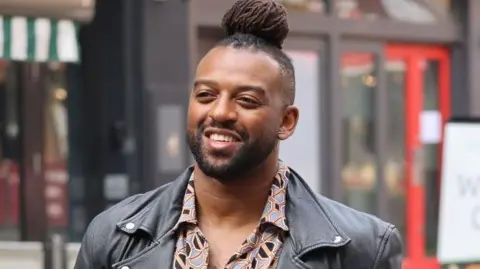

JLS star Oritse Williams, who also found fame on The X Factor, told BBC Breakfast there "isn't enough duty of care".

"It's a tough, tough game and you have to have a very thick skin," he said.

"When you haven't lived life, to go through trials and tribulations whilst being under the spotlight is a very difficult thing. And who is there to support?"

Oritse Williams said he had been through his own problems since finding boy band fame. "You're out there alone in this crazy, crazy world, where there are a lot of vultures. It's tough to navigate."

And Eoghan Quigg, who appeared on The X Factor with Payne in 2008, told 5 Live: "There needs to be more support because it's a fickle business, especially now with social media."

One Direction came third in The X Factor in 2010, behind winner Matt Cardle and runner-up Rebecca Ferguson - who shared her "devastation" at Payne's death.

She has previously said she suffered exploitation and bullying in the music industry.

"I've spoken for years about the exploitation and profiteering of young stars and the effects - many of us are still living with the aftermath and the PTSD [post traumatic stress disorder]," she wrote on social media.

Ferguson recalled getting a taxi with Payne to film The X Factor after meeting him at a train station.

"I can't help but think of that boy who was hopeful and looking forward to his bright future ahead. If he hadn't jumped on that train and jumped in that taxi I believe he would be alive today."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAnd Katie Waissel, who also appeared on The X Factor in 2010, has long campaigned for better support for those who appear on TV.

She spoke to the BBC last year about the "obscene amount of pressure" she felt under as a contestant on the show.

In response, a spokesperson for X Factor said "robust measures" were in place to support those involved in the show.

Speaking to BBC Radio 5 Live on Friday, she said young musicians were "naive" about entering into a reality television show. "It wasn't transparent what we were getting ourselves into... no-one knows what to expect."

Waissel called the music industry "very manipulative, coercive and deconstructive", saying "it sucks the soul out of people".

'Considerable' duty of care

But talent manager Jonathan Shalit said things had changed since 2010.

"Fortunately... a lot of lessons have been learned. The duty of care back then wasn't what it could have been [on reality shows in general]. Now the duty of care is considerable.

"I think it's very important to separate the emotions and the terribleness of what's happened to Liam... That is many years after he left One Direction... On the flip side, some members of One Direction have gone on to have great success and great enjoyment in the lives. It's not black and white."

He acknowledged that "fame is not what it seems to be... you've got a million friends but you've got no friends".

"I always say, artists are the most sensitive people in a very hard business."

And music management consultant Marcus Anthony told 5 Live on Sunday: "The music industry is aware that these thing need to be addressed, and big music events and conventions hold seminars and discussions about artist welfare and things are getting better.

"But some managers and labels will always prioritise the pound over the artist."

Africana55 Radio

Africana55 Radio