This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

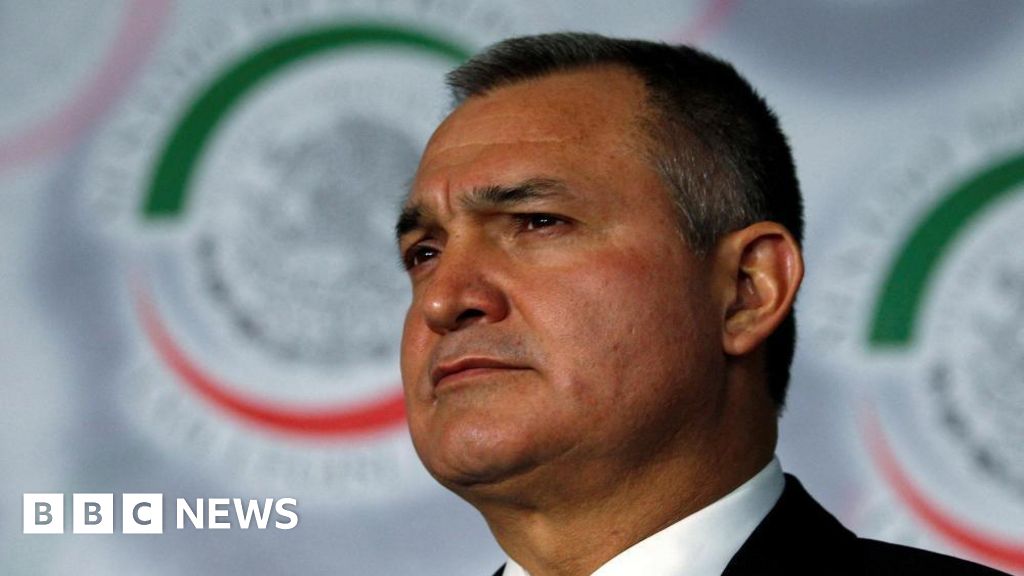

Appearing in a crisp suit and dark tie, Genaro García Luna – the highest-ranking Mexican official ever to be convicted in the United States – remained impassive as his sentence was handed down in a New York courtroom.

He was sentenced to more than 38 years in prison, as well as a $2m (£1.5m) fine. It was not the life sentence he could have received, but a jail term that the judge, Brian Cogan, felt reflected the severity of his crimes.

A small group of demonstrators outside court on Wednesday greeted the news with jubilation.

It marks the final chapter in the story of the most spectacular fall from grace in modern Mexico.

If anyone was Mexico’s drug war tsar – the chief architect and public face of the government’s security strategy under then-President Felipe Calderón – it was García Luna.

The sentence will also increase the pressure on Mr Calderón, too, who has always claimed he knew nothing of his security chief’s illegal activities.

García Luna has maintained his innocence. But to see him sentenced to almost four decades behind bars for drug-related crimes is more than even his fiercest critics dared to imagine while he was in office.

“His role in ramping up the war on drugs in Mexico from 2006 to a whole new level can’t be overstated”, says Falko Ernst, an independent drug war and security expert in Mexico.

“He championed a force-based solution against organised crime in Mexico like never before and revamped the state apparatus accordingly.”

To find that during his outwardly "proactive" stance on drug crime, he was in fact in bed with one of the region’s most violent and feared cartels, is emblematic of the kind of corruption and duplicity that makes Mexicans so sceptical of their politicians.

For Mr Ernst, the García Luna case also reveals a fundamental contradiction at the heart of the so-called "war on drugs".

“It shows how this recipe of a supposedly ‘good’ state acting against the bad guys and wiping them off the map doesn’t square with the realities on the ground in Mexico,” he argues.

As Mexico’s Public Security Secretary, Genaro García Luna was able to direct state resources and security forces against the Sinaloa cartel’s main rivals, an extremely brutal and violent criminal organisation called Los Zetas. In return for that favouritism, he received millions of dollars in bribes, for which he was convicted in a US federal court last year.

Suspicion always lingered over García Luna and there were open rumours of his involvement in organised crime, albeit with no legal proof published while he was in office.

At the heart of his defence was the argument that as a top public official embroiled in a complex internal security battle, García Luna was merely channelling the government’s funds and forces to where they were most needed, in order to neutralise the biggest threat in the country at that time.

The wisdom of prioritising certain groups over others is an ongoing debate in Mexico and, in essence, is as old as the drug war itself.

“Every single public security chief before him did the same thing,” argues Benjamin T Smith, professor at Warwick University and author of The Dope: The Real History of the Mexican Drug Trade.

“You basically have to choose one over the other because you need informants. Cartels are closed operations,” he says, “and the only way to enter them is to have informants on the inside. So, you back one crew over another.”

Mr Ernst echoes the same point: “Any administration is faced with the same dilemma. You have too much criminal power out there to confront it all at the same time so in one way or another you concentrate your resources and forces in one direction.”

García Luna, of course, was found to have been well-remunerated with millions in drug money by the notorious kingpin, Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán, for his services.

But even García Luna’s self-enrichment, argues Mr Ernst, reflects a “thin dividing line”.

“It's about whether corrupt and colluding behaviour by state officials serves a notion of public order as part of a pragmatic approach to pacification or is just about lining one’s pockets”.

The court in New York ruled that García Luna was guilty of the latter.

But some argue that even taking drug money could be argued to be part of the rules of the game and was known about by the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) at the time.

“Cartels demand you take money and wouldn’t trust you if you didn’t,” says Mr Smith. “It’s the old idea that you have to have complicity in corruption.”

Furthermore, García Luna’s lawyers argued, the case against him largely hinged on the testimony of convicted criminals and drug traffickers already serving prison time in the United States, whose trustworthiness was questionable at best.

The idea that the DEA, among other agencies, were aware of Garcia Luna’s complicity with the Sinaloa cartel begs the question as to why the Americans chose to prosecute him now, when he’s no longer a significant player and had been living in the US for several years.

“It’s worth asking whether these big cases have any real preventative effect,” says Deborah Bonello, an investigative journalist and the author of Narcas, which is about women in organised crime.

“García Luna left office in 2012 and the damage he did is already done, his conviction isn’t going to change anything. So it feels a bit like ‘too little too late’.”

Some suggest the "why now" question is potentially the result of the prosecutor’s office in New York actively trying to expose some of the most high-profile and embarrassing cases in recent Mexican administrations as a warning to other corrupt state officials.

Either way, the legacy of García Luna’s time in office is still being felt in Mexico.

During the arrest earlier this year of one of the co-founders of the Sinaloa Cartel, Ismael "El Mayo" Zambada, the Americans essentially acted alone and didn’t share any intelligence information with their Mexican counterparts ahead of time, points out Ms Bonello.

“They completely bypassed the Mexicans because of the corruption within law enforcement and the leaking of any intelligence to organised crime. The Americans went around the Mexicans completely – and that’s partly thanks to the protection of people like him," she says.

As a result of El Mayo’s arrest, stemming from an apparent betrayal by the son of his former partner, El Chapo, the Sinaloa cartel is engaged in a violent battle between warring factions.

Scores of people have been killed in the past few weeks and the security situation in the state is deteriorating fast, presenting the new Mexican President, Claudia Sheinbaum, with one of her first major challenges since taking office.

Some analysts see a direct line between the actions of García Luna and the current war within the Sinaloa cartel.

His strategy of favouritism was “fuel on the fire of conflict and criminal power in Mexico”, says Mr Ernst.

“It led to the extreme splintering of the criminal landscape to what we see today, which is much more aggressive towards civil society and towards the legal economy.”

A policy of playing favours with one side while hitting the other side hard has also seen “smaller and smaller groups trying to take control of local politics”, he says.

Given such a legacy of violence and corruption, few in Mexico will lament the demise of a man once considered too powerful to fall.

Africana55 Radio

Africana55 Radio