This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Tunis, Tunisia —

Tunis, Tunisia —

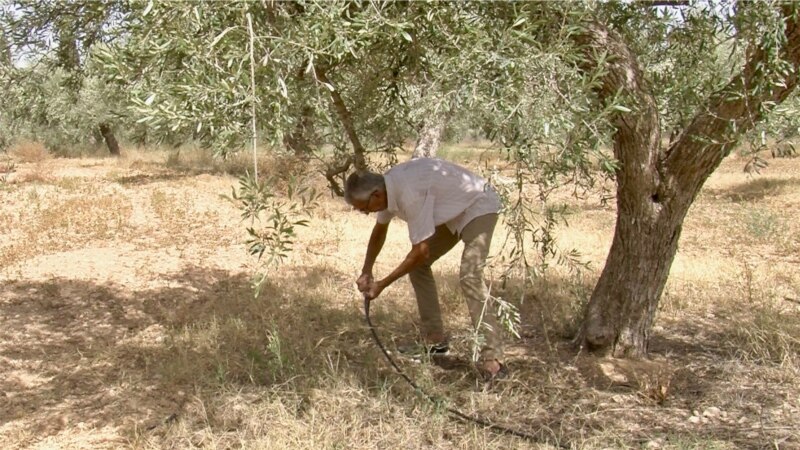

At his farm on the outskirts of Tunis, Karim Daoud is taking steps to accommodate a climate-changed future.

The cows now munching his hay are being phased out and replaced by more sustainable goats and sheep. His olive grove is watered by drip irrigation and ever-scarcer rains and Daoud is diversifying a traditional family business to include agricultural tourism.

“It’s been years since we’ve [been talking] about climate change, but I think today we’re really with our backs to the wall,” said Daoud, who began farming in the 1990s and is a member of Tunisia's farming union Synagri. “We need to find solutions and change our agriculture, so it respects the resources we have.”

Shaping Daoud’s bleak assessment are five years of drought that have hit agriculture hard in Tunisia — in ancient times a breadbasket of the Roman Empire. The North African country, highly dependent on rains and surface water for its population and industry, has seen its dams shrink to one-third or less of their capacity this year — although recent rains have offered a short-term respite.

The changing climate does not augur well for Tunisia or its Mediterranean neighbors. While September floods deluged nearby Libya, all of North Africa is expected to get hotter and dryer in the coming decades. The fallout, experts warn, could force many to migrate, with those who stay put facing increasing hardship.

Already Tunisia, along with Libya, count among the 25 most water-stressed countries in the world, according to the World Resources Institute, an environmental think tank. By 2050, average temperatures in Tunisia are expected to climb by up to 3.8℃, while rainfall is expected to decrease by at least 4%.

“The problem is very complex,” said Tunisian water management specialist Raoudha Gafrej. “It’s linked to the drought, but it’s also a failure in today’s policies of managing this crisis which is multi-dimensional.”

‘Throwing away’ water

Tunisia’s government has extended water restrictions that were imposed earlier this year. They include water bans for agricultural and green spaces and for washing cars and streets. Authorities are also drafting a 2050 water strategy that calls for more efficient water use and better management of extreme weather events, experts say.

But they note the strategy needs money to become reality — and that action is needed today.

“The water governance model is still to be clarified by the government at a time when urgent actions are needed to sustain water resources,” said Imen Rais, Tunisia freshwater program manager for the environmental group WWF (World Wildlife Fund).

Central to this, many believe, is a major rethink of Tunisian agriculture, notably export-driven irrigated farming, which consumes 80% of the country’s water supplies. Leaky pipes and other aging infrastructure also account for heavy water loss, Gafrej said.

“When you look at what comes from nature and what arrives to citizens, there’s between 30 to 50 percent of water lost,” she said.

At a market in Tunis, fruit seller Mongi Gaigi watches potential customers walk away after seeing the prices of his peaches.

“This year fruit is very expensive,” he said, “because of the drought.”

Tunisian harvests of citrus, peaches, dates and tomatoes also end up in European markets — driven by a water-consuming agriculture the country can ill afford, experts like Gafrej say.

“You’ll go to the markets and see 30 types of fruit — for a country that has no water,” she said.

Gafrej also points to mountains of uneaten couscous and bread scraps that end up in garbage bins.

“We throw away the equivalent of 900,000 loaves daily,” she said. “That’s the equivalent of 170 million cubic meters of water a year, through imported wheat.”

Like other North African countries, Tunisia has turned to desalination plants as one answer. Its 16 plants currently provide 8% of its potable water, with new plants underway. But that is a costly and partial answer, experts say.

Tapping old solutions

In the oases of southern Tunisia, rising temperatures, development and dwindling rainfall are threatening the country’s lucrative — and highly water dependent — date palm industry, with farmers drilling and pumping nonrenewable aquifers, often illegally, according to reports.

While some are turning to more environmentally friendly farming practices, others risk giving up and contributing to a climate migration that experts say will only grow.

“What keeps people in the south in many North African countries are the oases,” said Gafrej. “Palm groves create a microclimate — and without them life would be impossible in the desert. But they also consume a lot of water — without it, people will leave.”

In Tunis’ ancient Medina, social entrepreneur Leila Ben-Gacem is considering ancient answers for her own business, using roof-top pipes and traditional cisterns to capture and store water for the guesthouse she runs.

“This is a system that has been abandoned,” she said. “Today, with climate change, with drought, with all the water shortages we’ve been having, it could be a very important alternative."

At his farm, Karim Daoud is also being creative. He is enriching the hay he feeds his cows with food waste from a tomato processing factory and switching to hardier grape and olive varieties.

Workers are retooling the family farm to include rooms for tourists and business seminars as a way to diversify the family revenue. Daoud’s son, who left his job as a chef in Europe, is in charge of the cuisine.

Other farmers are also beginning to shift to more diversified, climate-friendly practices. But bigger changes are essential, Daoud and many others believe.

“We need a new vision when it comes to agriculture,” he said, describing a more holistic strategy shared across the Mediterranean region. “This demands a scientific and logistical support for farmers that currently doesn’t exist, or only a little.”

Africana55 Radio

Africana55 Radio