This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

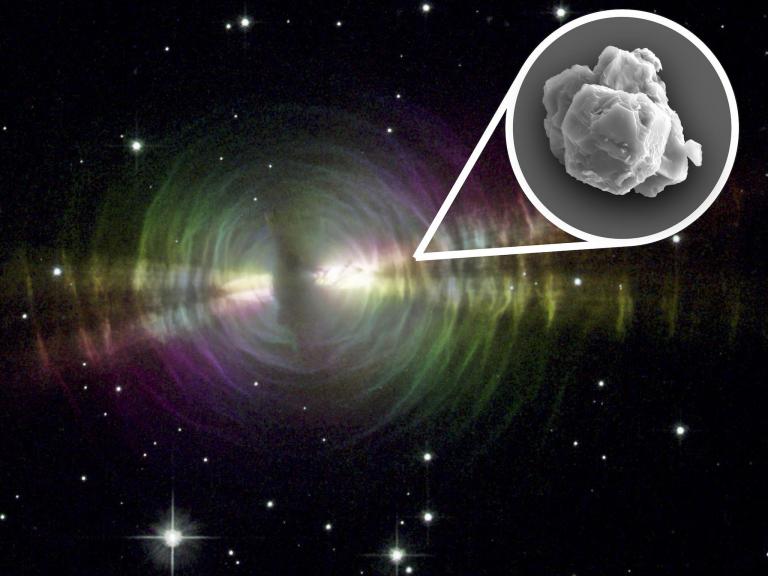

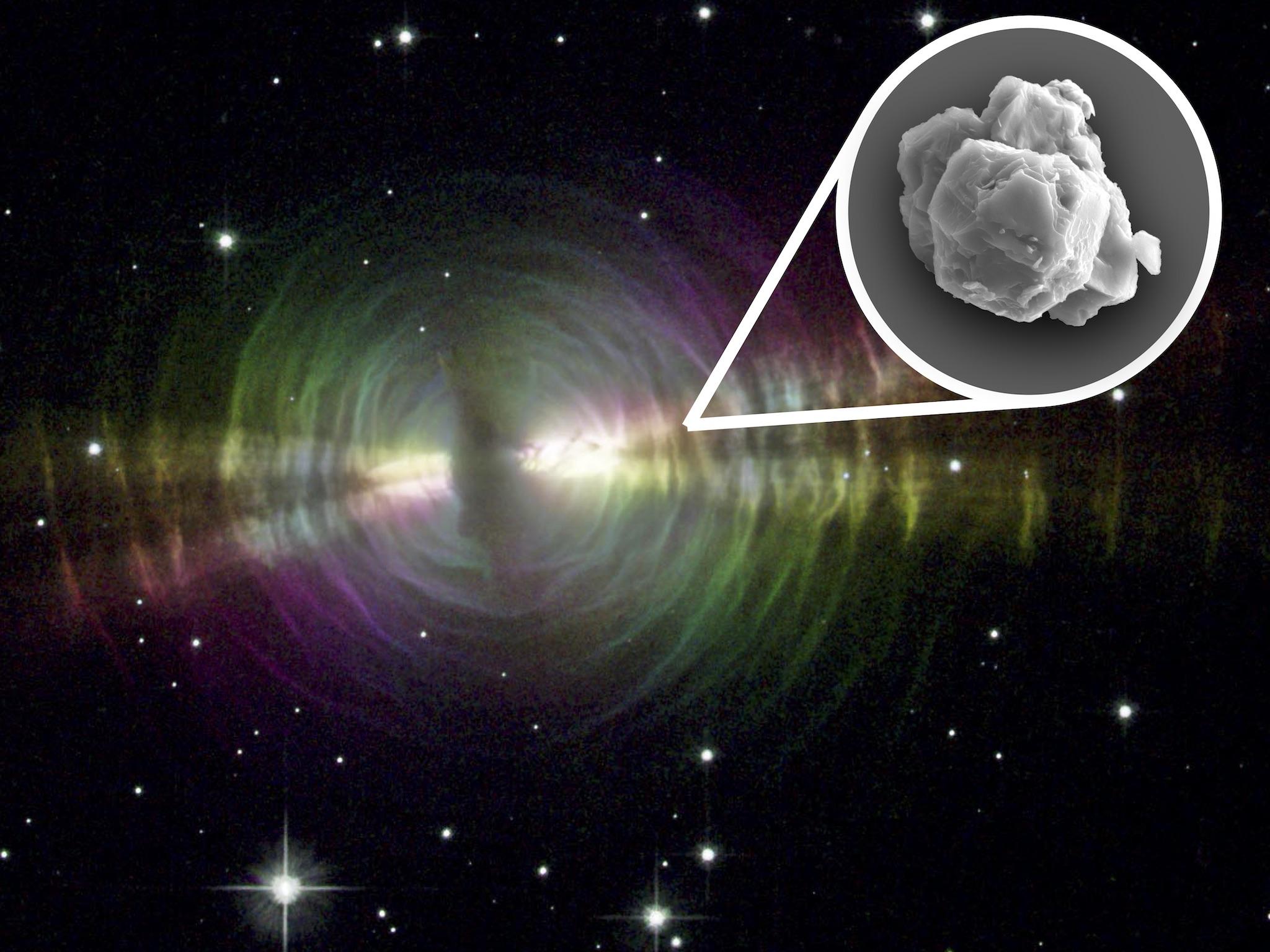

Scientists have found the oldest solid material ever discovered – a piece of stardust that formed some seven billion years ago.

Researchers describe the find as "solid samples of stars, real stardust" that is older even than our own sun.

Though it is older than any other solid material known to humanity, it only came to Earth 50 years ago when it dropped down on a meteorite.

Stars are born when dust and gas is attracted to each other in space, clumping and heating as it grows. Eventually, they will die and throw out material through space, which will go on to form new stars, planets or meteorites.

The newly discovered material was once part of that process, before travelling down to Earth as part of one such meteorite.

Created with Sketch.

Created with Sketch.

1/10

The eye of Hurricane Dorian as captured by Nasa astronaut Nick Hague from onboard the International Space Station (ISS) on 3 September

Nasa/EPA

2/10

The River Nile and its delta captured at night from the ISS on 2 September

Nasa

3/10

The galaxy Messier 81, located in the northern constellation of Ursa Major, as seen by Nasa's Spitzer Space Telescope

Nasa/JPL-Caltech

4/10

The flight path Soyuz MS-15 spacecraft is seen in this long exposure photograph as it launches from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan on 25 September

Nasa/Bill Ingalls

5/10

Danielson Crater, an impact crater in the Arabia region of Mars, as captured by Nasa's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft

Nasa/JPL-Caltech

6/10

A team rehearses landing and crew extraction from Boeing's CST-100 Starliner, which will be used to carry humans to the International Space Station at the White Sands Missile Range outside Las Cruces, New Mexico

Nasa/Bill Ingalls

7/10

Bound for the International Space Station, the Soyuz MS-15 spacecraft launches from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan on 25 September

Nasa/Bill Ingalls

8/10

Hurricane Dorian as seen from the ISS on 2 September

Nasa

9/10

A string of tropical cyclones streams across Earth's northern hemisphere in this picture taken from the ISS on 4 September

Nasa

10/10

The city of New York as seen from the ISS on 11 September

Nasa

1/10

The eye of Hurricane Dorian as captured by Nasa astronaut Nick Hague from onboard the International Space Station (ISS) on 3 September

Nasa/EPA

2/10

The River Nile and its delta captured at night from the ISS on 2 September

Nasa

3/10

The galaxy Messier 81, located in the northern constellation of Ursa Major, as seen by Nasa's Spitzer Space Telescope

Nasa/JPL-Caltech

4/10

The flight path Soyuz MS-15 spacecraft is seen in this long exposure photograph as it launches from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan on 25 September

Nasa/Bill Ingalls

5/10

Danielson Crater, an impact crater in the Arabia region of Mars, as captured by Nasa's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft

Nasa/JPL-Caltech

6/10

A team rehearses landing and crew extraction from Boeing's CST-100 Starliner, which will be used to carry humans to the International Space Station at the White Sands Missile Range outside Las Cruces, New Mexico

Nasa/Bill Ingalls

7/10

Bound for the International Space Station, the Soyuz MS-15 spacecraft launches from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan on 25 September

Nasa/Bill Ingalls

8/10

Hurricane Dorian as seen from the ISS on 2 September

Nasa

9/10

A string of tropical cyclones streams across Earth's northern hemisphere in this picture taken from the ISS on 4 September

Nasa

10/10

The city of New York as seen from the ISS on 11 September

Nasa

Lead author Philipp Heck, a curator at the Field Museum, and associate professor at the University of Chicago, said: "This is one of the most exciting studies I've worked on.

"These are the oldest solid materials ever found, and they tell us about how stars formed in our galaxy."

The materials examined in the study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences are called presolar grains-minerals formed before the Sun was born.

"They're solid samples of stars, real stardust," said Prof Heck.

However, presolar grains are tiny and rare, only found in about 5% of meteorites that have fallen to Earth.

But the Field Museum has the largest portion of the Murchison meteorite, a treasure trove of presolar grains that fell in Victoria, Australia, in 1969.

Presolar grains for this study were isolated from the Murchison meteorite about 30 years ago at the University of Chicago.

The process involves crushing the fragments of meteorite into a powder.

Co-author Jennika Greer, a graduate student at the Field Museum and the University of Chicago, said: "Once all the pieces are segregated, it's a kind of paste, and it has a pungent characteristic - it smells like rotten peanut butter."

This "rotten-peanut-butter-meteorite paste" was then dissolved with acid, until only the presolar grains remained.

Researchers compared the process to burning down a haystack to find the needle.

Once the presolar grains were isolated, the researchers figured out from what types of stars they came and how old they were.

Exposure age data allowed the researchers to measure their exposure to cosmic ray.

By measuring how many of the new cosmic-ray produced elements are present in a pre-solar grain, scientists can tell how long it was exposed to cosmic rays, telling them how old it is.

The researchers learned that some of the presolar grains in their sample were the oldest ever discovered on Earth.

Based on how many cosmic rays they had soaked up, most of the grains had to be 4.6 to 4.9 billion years old, and some grains were older than 5.5 billion years.

But the age of the presolar grains was not the end of the discovery.

As presolar grains are formed when a star dies, they reveal the star's history.

The researchers suggest that seven billion years ago, there was a bumper crop of new stars forming.

"We have more young grains that we expected," said Prof Heck.

"Our hypothesis is that the majority of those grains, which are 4.6 to 4.9 billion years old, formed in an episode of enhanced star formation.

"There was a time before the start of the Solar System when more stars formed than normal."

Scientists also found that presolar grains often float through space stuck together in large clusters like "granola", something that had not previously been thought possible on that scale.

Additional reporting by Press Association

Africana55 Radio

Africana55 Radio