This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

The recording studios at Afghanistan national radio and television where generations of male and female musicians and singers produced songs and melodies have gone silent for nearly two years.

The country’s Islamist Taliban regime does not air music on the national broadcasting network because their extreme interpretation of Islam considers it forbidden. Instead, they run so-called singsongs, which sound like chants with no music.

Known as the Taliban songs and nasheeds, the singsongs, voiced only by men, are mostly tributes to Taliban leaders, Islamic jihad and Afghanistan as a graveyard of foreign interventionists.

Many Taliban listen to these singsongs on their phones, in their cars and elsewhere as a source of entertainment, attachment and inspiration.

“Since the Taliban are religious zealots, they use songs for entertainment as well. It’s a form of competition for young Taliban to show off their voices. Songs are also designed to add some pleasure to an otherwise puritanical way of life,” said Wahed Faqiri, an Afghan analyst.

“[The Taliban] play it on radios and so, if you are in your car at that time and it's on the radio, you listen to it because it's kind of a captive/trapped audience,” Ali Latifi, a Kabul-based independent journalist, told VOA by email. “When I see Taliban playing them it's usually on their phones (even little Nokia ones) while they're standing or walking down the street (less often).”

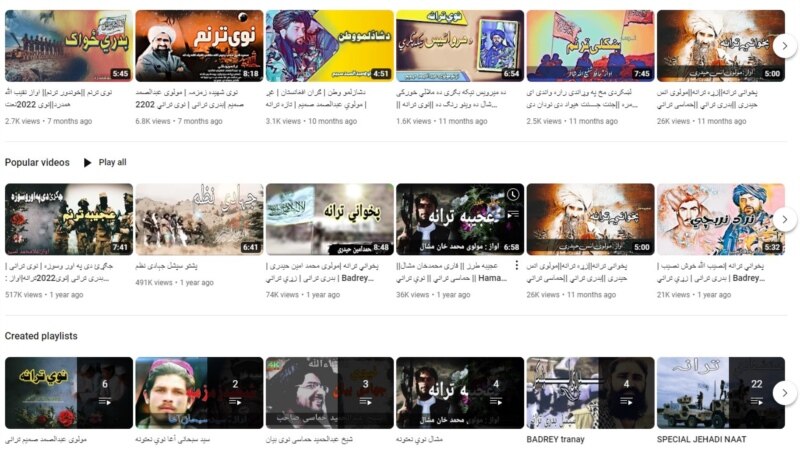

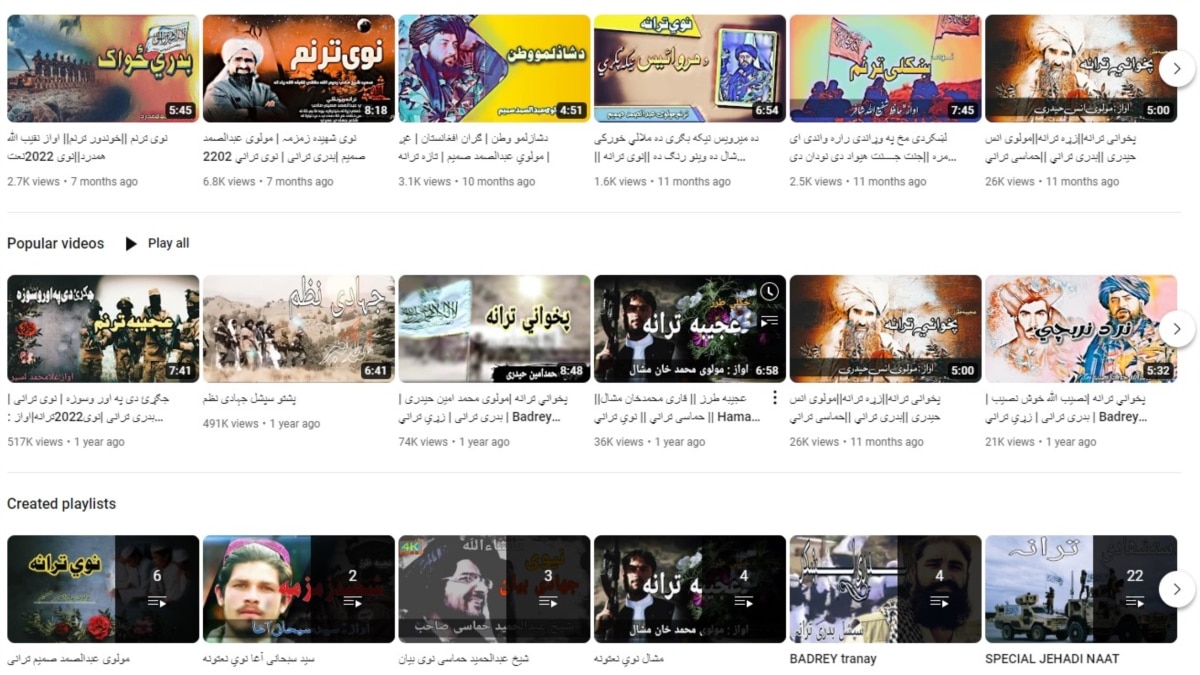

Since the Taliban’s ascent to power in Afghanistan, the group’s singsongs have increasingly found their way to digital platforms where they are accessible to global audiences. Social media companies often prohibit official Taliban accounts and groups, but the group’s sympathizers have maintained a presence under pseudonyms.

Given the group’s longstanding disapproval of television, pro-Taliban songs loaded to YouTube carry only still images of Taliban leaders and symbols. During their first reign in 1994-2001, the Taliban completely banned television and the group’s morality police broke down private TV sets and displayed them on poles to deter the public from watching television even in their homes.

As an insurgent group, the Taliban ran sophisticated digital propaganda campaigns including videos of violent attacks on Afghan and foreign soldiers.

‘Genocide of music’

The Taliban’s swift return to power in 2021 saw an exodus of artists, singers, musicians and journalists from Afghanistan.

Over the past 20 months, about 3,000 artists and singers have sought relocation outside Afghanistan, according to Artistic Freedom Initiative, an organization that offers free immigration and resettlement assistance for artists at risk.

The country’s National Institute of Music (ANIM) has been closed as all of its trainers, students and personnel were evacuated to Europe in 2021.

“We are witnessing a termination of the rich musical heritage of Afghanistan,” Ahmad Sarmast, ANIM director, told VOA while describing the many ways musicians and artists suffer under the Taliban rule.

While most popular Afghan musicians and singers reside abroad, those left in the country have reportedly quit music and have resorted to other jobs.

Sarmast said his ANIM staff and other artists are trying to keep the Afghan music alive in exile by organizing concerts and events in different parts of the world.

For many Afghans caught in recurring cycles of brutal wars, extreme and widespread poverty, and many social and cultural restrictions, music is a source of spiritual strength and a means to mental and psychological healing, experts say.

“The Taliban’s anti-music policies are turning Afghans into a mentally impaired nation,” warned Sarmast, who said the Taliban’s singsongs are praising and promoting violence.

A Taliban spokesperson received VOA’s request for comment on the regime’s policies about music but did not respond.

Africana55 Radio

Africana55 Radio