This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Family handout

Family handout“She’s going to rot in jail. No one is going to get her out.”

That was what prison guards told the family of Emirlendris Benítez. She disappeared in Venezuela in August 2018 after she and her partner - a taxi driver - were arrested while giving somebody a lift to the city centre.

She was arbitrarily accused of organising a plot to kill the president and, without a fair trial, given a 30-year prison sentence.

When she was taken to prison, she was pregnant. Guards beat her stomach despite her protestations, and she had a miscarriage.

Her family tell us she has faced torture in prison, including having her nails removed with a hammer.

The human rights group Foro Penal says there were 15,700 politically motivated arbitrary arrests in Venezuela between 2014 and 2023 and hundreds of people remain behind bars.

It is one of many ways the government has cracked down on dissent.

The BBC asked the government and prosecutor for a comment or interview and have received no response.

President Nicolás Maduro has been in power since taking over from his mentor Hugo Chávez in 2013 and is seeking re-election on Sunday.

Photos of him line the streets, and on the last day of campaigning in Caracas hundreds of buses were paid for to transport people from around the country to his final rally where free food parcels were handed out as an incentive to attend.

Venus, a woman at the rally, says Mr Maduro’s PSUV party has given her many “benefits”.

“We are here to support Nicolas Maduro to the end,” she says.

Iván, another supporter, says “to those who oppose us, those who say there is no democracy, that there is a dictatorship here… this revolution will continue to shine".

Even some supporters of Mr Maduro, though, have fallen victim to the crackdown on dissent.

A family member of Emirlendris, Ana (not her real name), spoke to us on condition of anonymity.

Her family voted for Nicolás Maduro, and Hugo Chávez before him, but say now “everything changed because we realised how justice works in Venezuela”.

“The government is desperate because it knows it has lost. Many people have opened their eyes and are realising the reality we live in in Venezuela. In the name of Almighty God, I hope that a new president wins for a better Venezuela.”

The last election was widely seen as neither free nor fair, many countries refused to recognise Mr Maduro as president, and the US imposed further sanctions on Venezuela.

For the first time in years, the opposition feel they have huge momentum and a lead in the polls - making it harder for the governing party to claim victory.

But the government has deployed a range of tactics with the armed forces, electoral and judicial authorities which it controls to pre-emptively suppress the opposition. They include detaining critics, uninviting EU election observers, and preventing millions of Venezuelans overseas from registering to vote.

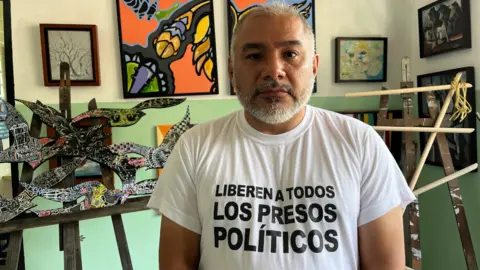

Alcides Bracho is a teacher who was detained on 4 July 2022 after going to a protest calling for better salaries.

“We are talking 800 days without an increase, and it is a salary of $3.50 per month,” he recalls.

But after the protest, he was arrested and accused of “terrorism”.

“They came to the house, approximately 22 people with long rifles. Guns that looked like those in action movies or boys’ video games. Without a search warrant.”

He was forced to stand naked for 72 hours while he was held in detention, with no access to food, water or a toilet after being sentenced to 16 years in prison for “conspiracy” and “criminal association”.

“I thought I was going to die.”

“If you want to start a business in Venezuela, let it be a prison. They charge you for everything. The state does not give you food,” he said of the lack of even the most basic things in jail.

He was eventually released in a prisoner exchange with the US last December in which 19 political prisoners were freed in exchange for Alex Saab, an accused money launderer with close links to President Maduro who was indicted in the US.

Despite what happened to him, Mr Bracho wants to keep fighting.

“If we all keep quiet, if no-one does it, there is no fighting.”

“There is an upswing in repression. We are very worried. It’s not like I can start my life again, I don’t have a safe space.”

The opposition leader, María Corina Machado, was banned from running in Sunday's election, dozens of her team have been detained, and even food stalls that served her have been shut down.

Most television and radio stations are state-run, with many other digital media outlets being blocked.

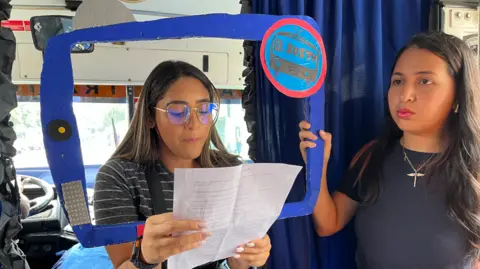

Bus TV is a campaign of volunteers who read out “real news” on buses around the country.

Andrés Brancovic is one of the volunteers. He thinks “censorship” could affect the election.

“Twitter is one of the most used apps in Venezuela right now, because people can post what they want and see what is happening. But people who just have national TV in their houses - they don’t see what is happening with the opposition.”

“All the news is in favour of the regime,” he says.

Despite having the world’s largest known oil reserves, Venezuela is desperately poor. More than half the population of Venezuela lives in poverty, and nearly eight million people have fled the country - contributing to a migration crisis on the US border.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesJhonatan Marcano lives with his family of five in one small room.

He goes out fishing every day in a rubber tyre, often in dangerous tides, to feed his family.

He cannot afford a boat, nor fuel for one. He relies on the tide to bring him back to land every day.

“I always voted for the people who are in charge. Chávez inspired confidence in me.”

Now, though, he is undecided: “Help doesn’t come, what you need most does not come to you. I’m so disappointed in the party.”

President Maduro blames US sanctions for the country’s woes, but critics also put it down to corruption and economic mismanagement.

There are reasons the West wants to improve relations with Venezuela - the oil and natural resources the country has, the fact Iran, China and Russia rely on Venezuela as an ally in the West, and because they do not want the US migration crisis to worsen.

But it is unlikely sanctions will be lifted and the government recognised if the vote is seen as unfair again.

Additional reporting by Vanessa Silva.

Africana55 Radio

Africana55 Radio